By Diego Castañeda Garza

Some scholars would argue that the world was first globalised as far as five centuries in the past when the European conquests of the new world brought its sinews to the old. When silver began to circulate the globe as the first truly global commodity (Flynn & Giráldez 2004). However, for most economists, the world was first globalised as close as two centuries ago, after the end of the Napoleonic wars, with the rising industrial power of the British nation and the peak of its imperial power (O’Rourke & Williamson 2002).

In any case, five or two centuries ago, globalisation has always implied distributional effects, winners and losers in each corner of the world it has reached. First, the enrichment of political and economic elites in the colonial powers and its colonised countries and then again at the time of the great divergence when countries started to industrialise, but most of their populations at either time did not. Today’s globalisation is not different; we have designed it that way.

Since the beginnings of trade theory with David Ricardo’s Principles of Political Economy and Taxation and the introduction of the idea of comparative advantage, the existence of distributional effects was a distinct aspect of international trade. Trade specialisation following national comparative advantages strongly favoured some sectors and industries and hurt others. The gains for trade were never distributed equally among all sectors; the distribution of wages, benefits and rents entailed by necessity winners and losers. Nevertheless, for a long time, economists, when engaging the public about international trade and its benefits, when speaking and teaching about Ricardo’s ideas (and their extensions through the Hecksher-Ohlin model, i.e equalising international prices and wages entails winners and losers) obviated this basic result:often not all benefit from trade.

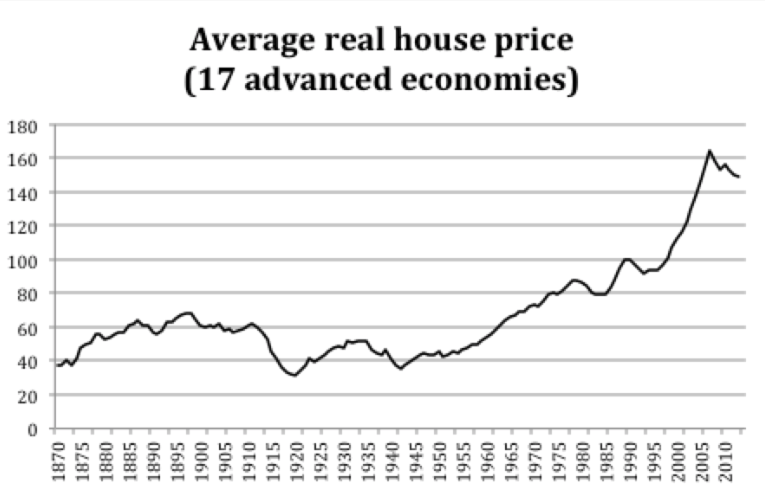

As Polanyi (1944|2017) argued, the attempt to disembed politics from the economy entails risks. In the past, the negligence encouraged by not recognising the distributional consequences of globalisation and the failure to address them have been a source of social and political instability. Ignoring the people propelled backlashes against globalisation more than a century ago. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, one of those backlashes occurred. The consequence of the backlash was that several countries (i.e. Germany, France, Sweden) that previously had been moving towards trade liberalisation halted their movement. They started to look backwards to protectionist policies. In time, the outbreak of the Great War finally ended the so-called first globalisation (O’Rourke & Williamson 1999).

From this historical experience, we should have learned an essential lesson in our times, but we failed to do so. The lesson is that there is nothing natural nor granted in the process of achieving a sustainable global economic integration. Similarly, there is no linear path of development that necessarily arrives at a hiper-globalised world. Globalisation today, or in the 19th century, is an international political construct supported by the equilibrium of power and interests between existent states. The inequality embedded in our economic systems, in the same way, exists largely due to political economy reasons.

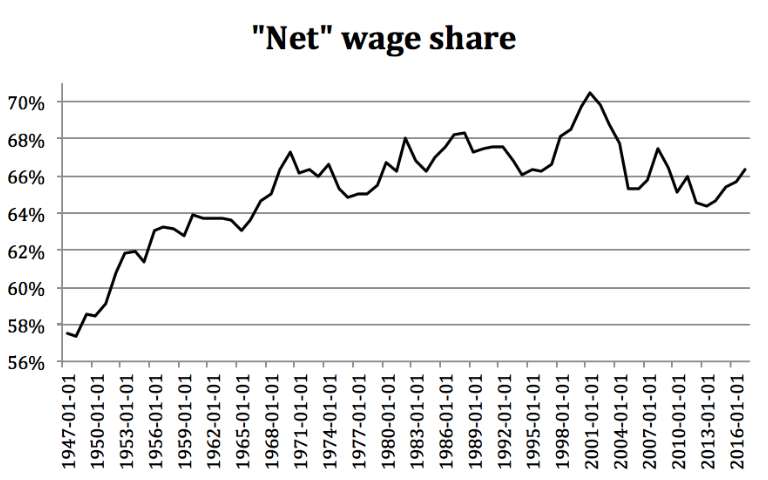

After the 1970s, the end of the trente glorieuses, a new policy framework characterised by deregulation, liberalisation and the capture of the state by private interests took root around the world. It propelled the new second globalisation. Over the last four decades, we have been living in an increasingly interconnected world. For decades, the rate of growth of international trade surpassed the growth rate of the world economy, a phenomenon often called hyper-globalisation. Underlying this era, we have witnessed high-speed economic growth in some regions, but also growing inequalities and accelerated environmental degradation. Now, at the end of this period, there is a trend break in which the costs of the politics of previous years are manifesting themselves. We are witnessing a reversal of fortune in which China is returning to a prominent role in the global economy. Meanwhile, the advanced countries that defined the rules of the world economy are riddled again with backlashes, political instability, and economic stagnation.

These already turbulent times got compounded with the pandemic and the economic fallout it unleashed. However, this bleak scenario also presents us with opportunities. The current sense of crisis around the world, especially in the advanced countries, provides the imperative to solve the “twin problems” of the 21st century: rising national inequalities and climate change. It is a unique opportunity to redesign globalisation under new principles. It represents a chance to redesign it around principles that privilege equality, sustainability, and the existence of global public goods, like global public health and our environment.

The Great Lockdown, a necessary response due to the Sars-CoV-2 pandemic, has served as a mirror for nations to look at themselves, it has made their problems even more evident. The global nature of the current crisis and the way it interacts and exacerbates within-country economic inequalities exhibits economic weaknesses, intensifies geopolitical conflicts, and highlights the need for global solutions. History has yielded us with a perfect context to change globalisation. It is an opportunity to work towards the solution of the twin crisis and, in the process, create a new globalisation 3.0.

Globalisation 3.0 should be constructed as a more sensible process of economic integration. It should be embedded with different rules and norms of good behaviour, that privileges the needs and preferences of the world population and not the preferences of global elites. Instead of focusing on capital flows and finance, it should focus on public health, climate change, labour rights. It should do a better job of representing the priorities of developing countries. Historical experiences either in the times of the gold standard, Bretton Woods or the current one, shows to us that the rules give the shape of globalisation. The rules we agree to uphold, the priorities we set.

The construction of globalisation 3.0 should ensure countries have enough policy space to guarantee economic, political, and social stability. In that sense, instead of reaching from the global to the national in what constitutes a politically fragile architecture, the new rules should reach from the national to the global. It should ensure the states liberty to pursue pragmatic policies that enhance their development capabilities. Room to do active industrial policy, to correct economic inequalities through adequate taxation. That space implies the need to accept the embeddedness of politics in economic matters, to accept that economic policy is unsustainable without addressing mass politics.

To fix our problems, the existence of tax havens, climatic disaster, the surge in inequalities, and their feedback loop towards political life is a necessity of our time. But it will not be possible if we choose to preserve globalisation in its current form. There is no need for a tradeoff between national policies and true global imperatives. Both can be aligned, but they require that we finally learn the lessons of history and redesign our global economy in such a way to leave room for both. In the end, it is only the harmony between national and global interests that will allow us the capacity to respond to our challenges. Redesign the functionings of the world economy is the path to preserve social stability, develop our countries and respond to the crises of our times.

About the author: Diego Castañeda Garza is an economist and economic historian; he is the head of the economic cluster at Agenda for International Development (A-ID) and a coordinator of the Economic History Working Group at the INET’s Young Scholar Initiative.

This article is a runner up in an essay competition held by the UNCTAD YSI Summer School on Globalization and Development Strategies. Participants of the school worked with senior scholars to fine-tune their drafts, and the top-5 articles were published here. For other articles in the series, please click here.

About UNCTAD UNCTAD is a permanent intergovernmental body established by the United Nations General Assembly in 1964. Its headquarters are located in Geneva, Switzerland, with offices in New York and Addis Ababa. UNCTAD is part of the UN Secretariat, reports to the UN General Assembly and the Economic and Social Council, and are also part of the United Nations Development Group.