Economists have suggested several competing theories to explain the phenomenon of the declining wage share, as it has been falling globally for several decades. In the case of the US, two specific factors can explain a significant part of the decline: The increase in economy-wide depreciation and the rise of imputed rents as a share of total GDP.

A number of economic studies in recent years have documented the declining wage share in many countries around the world. The wage share is the part of GDP that can be attributed to labor income (wages) and is usually assumed to fluctuate around 60% while most of the remaining part of GDP is accounted for by capital income, such as rents from housing, income from Intellectual Property Products, capital gains and stock dividends, etc.

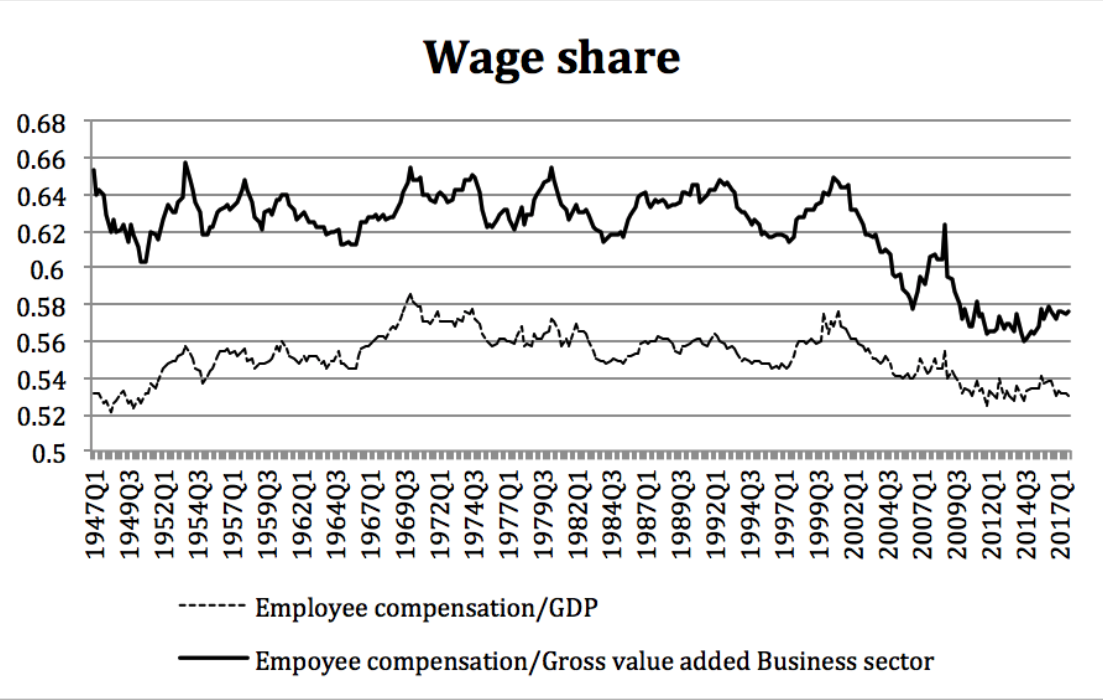

The chart below shows that the US wage share has fallen from almost 58% two decades ago to just 53% as of today, a decline of about 5 percentage points. This phenomenon is concerning insofar as the majority of the population derives most of their income from wages whereas capital income only accounts for a small share for most people. The reason is, of course, that capital ownership tends to be highly concentrated: About 75% of the US total wealth being owned by the top 10%. While home ownership tends to be much more dispersed, it can actually vary quite significantly from country to country. In the US, the home ownership rate exceeds 60%, but it is significantly below what it was before the financial crisis when it almost hit 70%.

Source:BEA

There are several competing (but not mutually exclusive) hypothesis that have been put forward to explain the trend of the falling wage share. Some authors have focused on the decline of the bargaining power of labor, either as a result of eroding labor unions, or the result of globalization as a number of low-wage countries like China entered the global economy during the late 1980s.

Alternatively, some papers have suggested that monopoly power in many industries has increased, thus putting downward pressure on the wage share as markups are rising. Finally, some post-keynesian economists have emphasized increasing financialization as a possible cause.

In what follows, I will focus on yet another explanation that might explain part of the downward trend of the gross wage share. While GDP is usually defined as the sum of all the income streams in the economy, there are several categories that national statistics offices include in the GDP calculation, but technically there is no income stream flowing at all. There are two items that stand out in particular because they are quantitatively the most important: Depreciation of capital and imputed rents.

Depreciation of physical assets is included in the GDP calculation because it is counted as a cost of production to firms. From an accounting point of view, depreciation is the allocation of cost of an asset over its useful lifespan. Since depreciation expenses can be offset against a firm’s taxable profits, firms might actually have an incentive to overstate annual depreciation expenses.

US tax law allows firms to depreciate all kinds of assets that are used in the production process, ranging from nonresidential structures to all kinds of industrial equipment, and even Intellectual Property Products (IPP). Over the last few years depreciation as a share of GDP has increased mostly as a result of two factors.

First, more and more companies increasingly rely on modern technologies that tend to depreciate at a fairly rapid pace. Equipment like computers, smartphones, software, etc. tend to become obsolete within just a couple of years: According to the BEA, each of these items has a lifespan of only two to three years when it must be replaced. Compare this with other industrial equipment, which has an average lifespan of half a decade at least, with non-residential structures easily approaching a lifespan of two decades.

Second, US corporations have produced an increasing amount of intangible products in recent decades (IPP). This could be a patent, for example, which is basically a monopoly right granted by the government for a specified time period, usually 20 years in the US. As companies can depreciate all cost expenses of their patent over its useful or legal life, companies might also have an incentive to overstate their expenses because they can be offset against their tax liabilities. As the share of intangible assets has increased significantly over the last few years, so have depreciation expenses caused by the production of IPP.

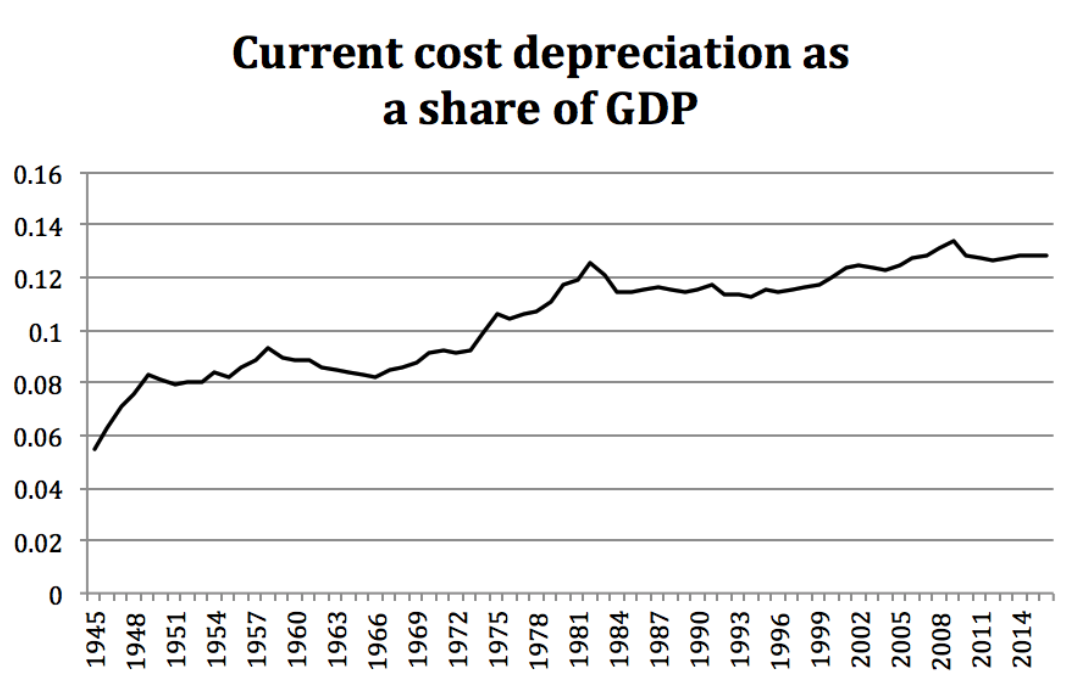

The chart below shows that depreciation as a share of GDP has increased from about 6% in the postwar period to almost 13% as of today and this significant rise can account to some extent for the decline in the gross wage share. Most of the increase in depreciation can be explained by the rise of modern technologies, which tend to have a significantly lower lifespan and thus become obsolete much more quickly, as well as the increasing importance of IPP in today’s economy.

Source:BEA

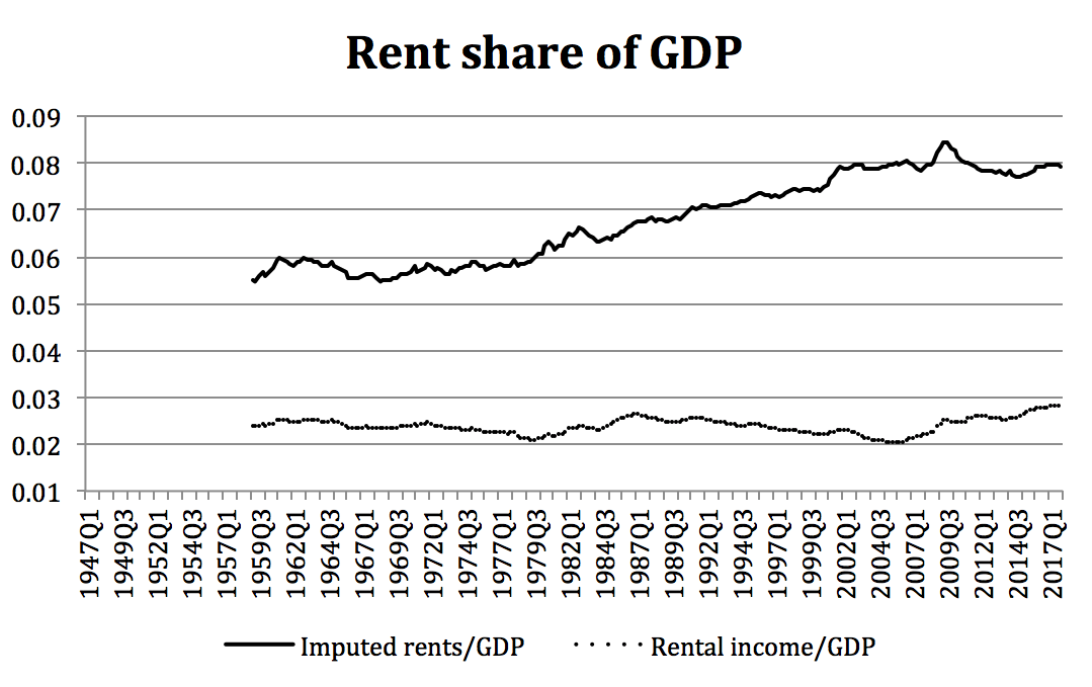

The second large item that might have put downward pressure on the wage share is the increase in the rent share of GDP. In the case of the US, it is mostly imputed rents, the rent-equivalent a house owner would pay to himself in rent, that have risen significantly.

Source:BEA

Imputed rents are included in the GDP statistics even though there is technically no income stream flowing to anyone because otherwise a country that consists for the most part of renters (like Germany) would have an “inflated” GDP figure. Consider two countries, A and B, which are equal in every aspect with one single exception. Let’s say that in country A, I live in your house and pay rent to you and you live in my house and pay rent to me, whereas in country B we both live in our own houses. If we exclude imputed rents, country A would have higher GDP than country B simply because we pay rent to each other even though the two countries are equally productive (by assumption). Imputed rents are obviously derived from the value of the underlying dwelling.

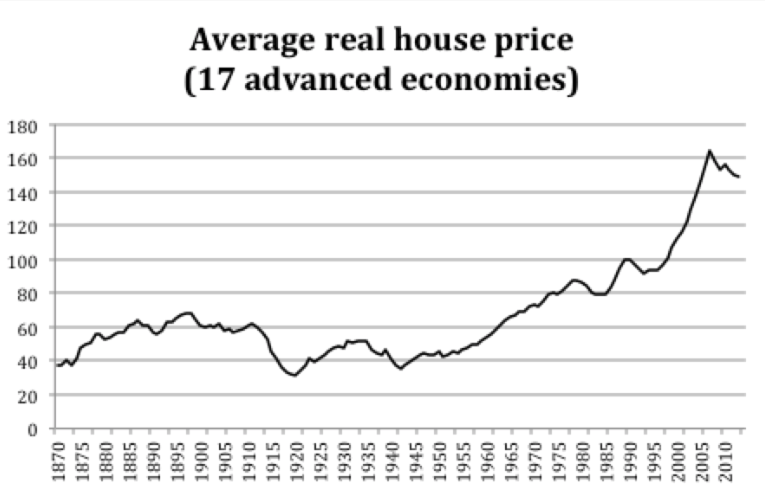

As most advanced economies have experienced spectacular house price appreciations over the last couple of decades, mostly a result of supply-side restrictions rather than “speculative bubbles”, imputed rents surely have increased more or less in tandem. In the case of the US, imputed rents have actually surged from about 6% of GDP in the 1960s to about 8% of GDP as of today. The increase in the rent share of GDP, mostly a result of rising house prices being accompanied by increasing imputed rents, thus also puts some downward pressure on the gross wage share.

Source: Jorda, Schularick and Taylor (2016) Macrohistory database

We have therefore two items, economy-wide depreciation as well as imputed rents, which account for an increasingly large share of total GDP despite the fact that both categories actually do not represent any income streams in the classical sense.

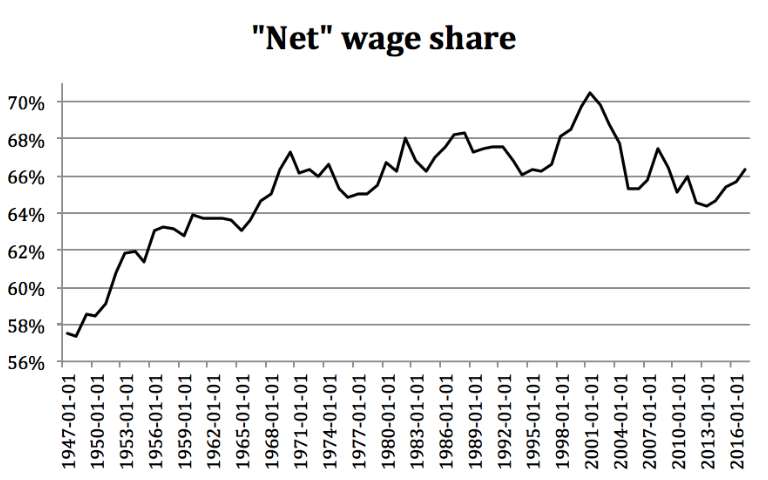

It is exactly for that reason that some economists have argued that from an inequality point of view we should rather focus on the net wage share, meaning net of depreciation. Furthermore, as I have explained above, there is an argument to be made that such a net measure should also net out imputed rents (and potentially other imputed income streams that are included in the GDP calculations), thus focusing entirely on actual income streams instead. Doing so cancels out most but not all of the downward movement of the wage share one can observe across countries in recent decades. For the US, the graph below shows that the “net wage share”, adjusted for depreciation and imputed rents, is not significantly lower today than what it was from the late 1960s onwards.

Source:FRED

About the Author: Julius Probst is a Phd student at the Economic History department of Lund University in Sweden. His main research area is long-term economic growth with a special focus on economic geography.

Henry George explained the continuous downward pressure on wages in 1869. Check him out first!