By Pierre Ortlieb.

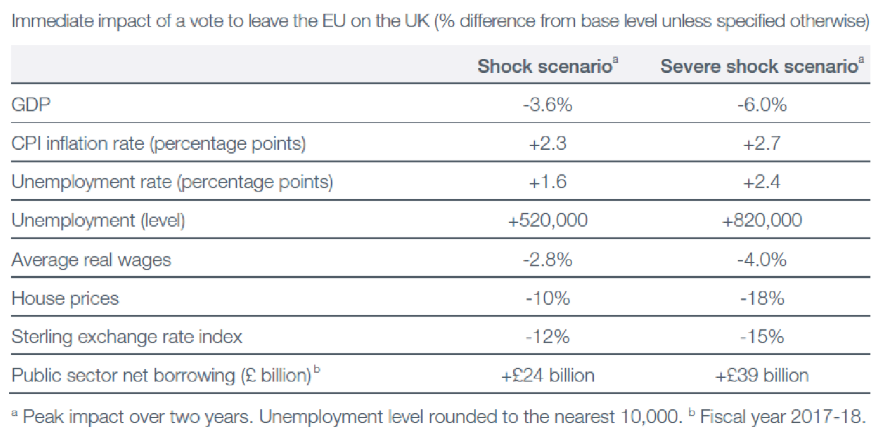

On June 10th, 2018, Swiss voters participated in a referendum on the very nature of money creation in their small alpine republic. The so-called “Vollgeld Initiative,” or “sovereign money initiative,” on their ballots would have required Swiss commercial banks to fully back their “demand deposits” in central bank money, effectively stripping private banks of their power to create money through loans in the current fractional reserve banking system.

In the build-up to this poll, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) tailored their statements on credit creation based on their audience: when speaking to the public, the SNB chose to promulgate an outdated “loanable funds” model of money creation, while it adopted an endogenous theory of credit creation when speaking to market participants. This served to mollify both audiences, reassuring them of the ability and sophistication of the SNB. Yet the contradicting stories offered by the SNB are part of a broader trend that has emerged as central banks have expended tremendous effort on trying to communicate their operations, with different banks offering different explanations for how money is

created. This risks damaging public trust in money far more than any referendum could.

***

At the SNB annual General Shareholders Meeting in April 2018, Governor Thomas Jordan was verbally confronted by two members of the audience who demanded Jordan explain how money is created – Jordan’s understanding of credit, they argued, was flawed and antiquated. Faced with this line of questioning, Jordan rebutted that banks use sight deposits from other customers to create loans and credit. The audience members pushed back in disagreement, but Jordan did not waver.

On the surface, Jordan’s claim on money creation is an explanation one would find in most economics textbooks. In this common story, banks act as mere intermediaries in a credit creation process that transforms savings into productive investment.

However, only months earlier, Governor Jordan told a different story in a speech delivered to the Zürich Macroeconomics Association. Facing an audience of economists and market professionals, Jordan had embraced a portrayal of money creation that is more modern but starkly opposed to the more folk-theoretical, or “textbook” view. Jordan described how “deposits at commercial banks” are created: In the present-day financial system, when a bank creates a loan, “an individual bank increases deposits in the banking system and hence also the overall money supply.” This is the antithesis of the folk theory offered to the public, presenting a glaring contradiction. Yet the SNB’s duplicity is part of a broader trend: central banks are unable to provide a unified message on credit creation, both internally and among themselves.

For instance, in 2014, the Bank of England published a short, plainly-written paper that described in detail how commercial banks create money essentially out of nothing, by issuing loans to their customers. The Bank author’s noted that “the reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks,” and sought to correct what they perceived as a popular misinterpretation of the credit creation process. Norges Bank, Norway’s monetary authority, has made a similar push to clarify that credit creation is driven by commercial banks, rather than by printing presses in the basement of the central bank. Nonetheless, other central banks, such as the Bundesbank, have gone to great lengths to stress that monetary authorities have strict control the money supply. As economist Rüdiger Dornbusch notes, the German saving public “have been brought up to trust in the simple quantity theory” of money, “and they are not ready to believe in a new institution and new operating instructions.”

***

While this debate over the mechanics of money creation may seem arcane, it has crucial implication for central bank legitimacy. During normal times, trust in money is built through commonplace uses of money; money works best when it can be taken for granted. As the sociologist Benjamin Braun notes, a central bank’s legitimacy depends in part on it acting in line with a dominant, textbook theory of money that is familiar to its constituents.

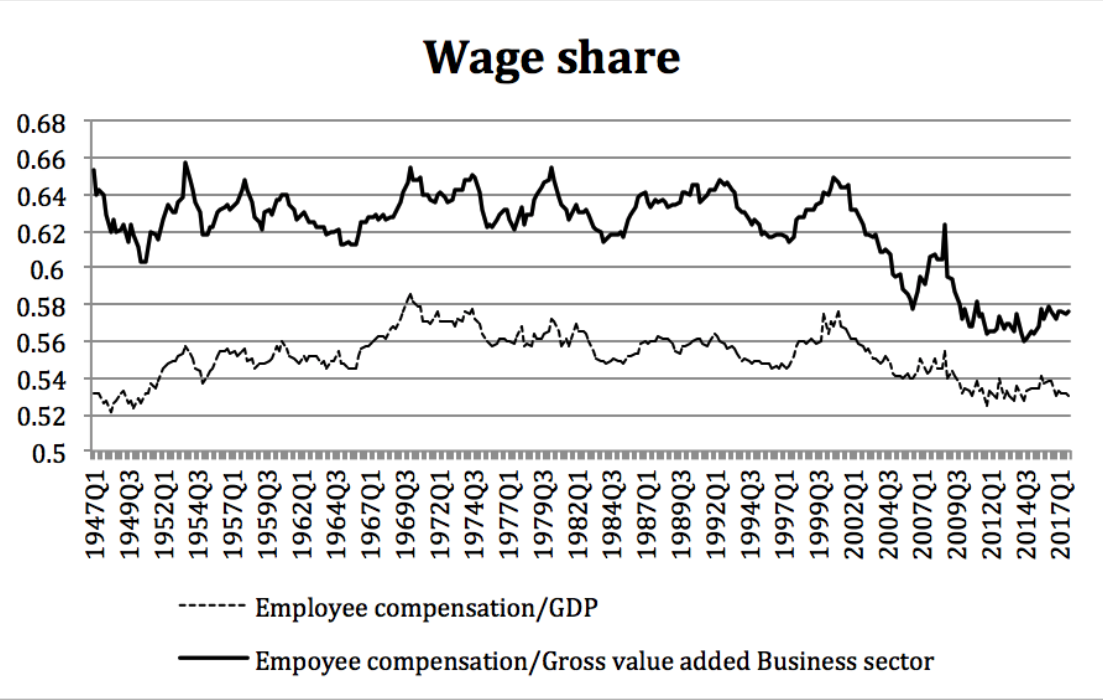

Yet this is no longer the case. Since the financial crisis, this trust has been shaken, as exemplified by Switzerland’s referendum on sovereign money in June 2018. Faced with political pressures and uncertain macroeconomic environments, some central banks have had to be much more proactive about their communications, and much more frank about the murky nature of money. As quantitative easing has stoked public fears of price instability, monetary authorities including the Bank of England have sought to clarify who really produces money. In this sense, taking steps to inform the public on the real source of money – bank loans – is a worthwhile step, as it provides constraints on what a central bank can be reasonably expected to do, and reduces informational asymmetries between technical experts and lay citizens.

On the other hand, a number of central banks have taken the dangerous approach of simply tailoring their message based on their audience: when speaking to technical experts, say one thing, and when speaking to the public, say another. The janus-faced SNB is a case in point. This rhetorical duplicity is important as it allows central banks to both assuage popular concerns over the stability of money, by fostering the illusion that they maintain control over price stability and monetary conditions, while similarly soothing markets with the impression that they possess a nuanced and empirically accurate framework of how credit creation works. For both audiences, this produces a sense of institutional commitment which sustains both public and market trust in money under conditions of uncertainty.

Yet this newfound duplicity in central bank communications is perilous, and risks further undermining public trust in money should they not succeed in straddling this fine line. Continuing to play into folk theories of money as these drift further and further away from the reality of credit creation will inevitably have unsettling ramifications. For example, it might lead to the election of politicians keen to exploit and pressure central banks, or the production of crises in the form of bank runs.

Germany’s far-right Alternative für Deutschland, for instance, was founded and achieved its initial popularity as a party opposed to the allegedly inflationary policies of the European Central Bank, which failed to adequately communicate the purpose of its expansionary post-crisis monetary program. Once a central bank’s strategies and the public’s understanding of money become discordant, they lose the ability to assure their constituents of the continued functioning of money, placing their own standing at risk.

Central banks would be better off engaging in a clear, concise, and careful communications program to inform the public of how credit actually works, even if they might not really want to know how the sausage gets made. Otherwise, they risk further shaking public trust in critical monetary institutions.

About the Author: Pierre Ortlieb is a graduate student, writer, and researcher based in London. He is interested in political economy and central banks, and currently works at a public investment think tank (the views expressed herein do not represent those of his employer).