The response to climate change is one of the most pressing policy issues of our time. Carbon trading assets are currently worth more than $100 billion. This market is expected to reach $3 trillion by 2020. In Stabilizing an Unstable Economy Hyman Minsky notes that the markets for financial assets are inherently unstable, leading to the cyclical behavior of the economic system. How effective then are market-based solutions to solving climate change? It might just be that carbon markets have not reduced environmental instability and may increase financial instability of the entire economic system.

The core of carbon trading isnot trading of physical GHGs, but the trading of the right to emit GHGs and the unit of account is a ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e). The carbon market stems from the Kyoto Protocol, and its specifics are target of discussion as scholars debate about the legal characteristics of the carbon unit. Some countries view it as a commodity while others see it as a monetary currency.

Under the Kyoto Protocol trading mechanisms were made up of three types: international emissions trading, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), and Joint Implementation (JI). The European Union Emission Trading System (EU ETS) is the world’s largest carbon market. According to the 2016 ICAP worldwide emissions report, there are 17 emissions trading systems operating around the world, which are currently pricing more than four billion tons of GHG emissions. In 2017, two new systems will be launched: China and Ontario, the former will become the largest of such systems, and will drive worldwide coverage of ETSs to reach seven billion tons of emissions by 2017.

Voluntary markets exchanges (carbon markets outside the Kyoto) are also on the rise because they make trading, hedging and risk management easier by providing liquidity. Furthermore, they develop sophisticated financial instruments such as CER futures, options, and swaps, which will help establish a price forecast for carbon. Some of these markets are the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX), Multi-Commodity Exchange of India (MCX), and Asian Carbon Trade Exchange.

Sustainable Development

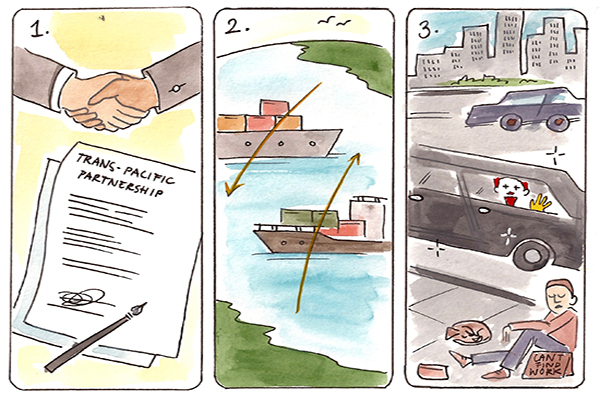

From their foundation, carbon markets have failed to address the underlying root causes of climate change. They divert money from technological investment that will actually reduce the use of fossil fuels towards the financial markets. Furthermore, they are causing instability in the environment through the use of carbon offsets, which have caused massive green grabs to occur in the global South, and through outsourcing emissions to developing nations. Carbon offsets were created by Kyoto to describe emissions reductions projects that are not covered by an ETS. For instance, tree plantations, fuel switches, wind farms, hydroelectric dams…etc.

The world’s richest have over-consumed the planet to the brink of ecological disaster. Instead of reducing emissions within their own countries, they have created a carbon dump in poorer regions. As such, emissions trading system represent the world’s greatest privatization of a natural asset. The Kyoto protocol is set up in a way that carbon sink projects (forests, oceans, etc.) are only accepted when people with official status manage them. Hence, it expands the potential for neocolonial land-grabbing to occur. Rainforest inhabited by indigenous people will only qualify as “managed” under the Kyoto when they are run by the state or a registered private company.

Furthermore, carbon trading has also failed to reduce global GHGs emissions. When a country claims to have reduced its carbon emissions, one must question whether it is by adopting low-carbon technologies, like how Sweden used well-crafted public policies and market incentives to decarbonization, or by outsourcing its emissions to another country, most likely to developing nations. For example, the Chinese government has questioned whether the emissions coming out of Chinese smokestacks were really ‘Chinese’ or should they be accounted to those in Western countries who are consuming Chinese goods or are owned by joint venues with developed countries. The question arose because Europe claimed that it was making progress on climate change based on tabulating the physical locations of molecules. Larry Lohmann phrased it perfectly when he said that Europe’s statistical claim “[conceal[s] an important fact that it has offshored much of its emissions [to China].” Take the UK, it has not in fact reduced its emissions it merely offshored one-third of its emissions by not accounting for emissions of imported goods and international travel.

Carbon markets have had many fraudulent activities within them. In 2002, the UK had a trial emissions trading scheme worth £215 million, which resulted in fraud. Three chemical corporations had been given £93 million in incentives when they had already met their reduction target. Another famous fraudulent activity revolved around international offset projects whereby companies would create GHGs just to destroy them and make money off of the credits.

As nature is being commodified and privatized,the current policies for sustainable development, under the guise of conservation, are alienating the poor from their means of livelihood by securing resources for organizations. These indigenous people — land users — are seen as needing to be saved from their primitive ways and to be educated on utilizing sustainable development within the bounds of the market. If it sounds like colonialism that is because it is.

For example, there exists specific types of green grabs known as conservation enclosures where the market is seen as the best way to conserve biodiversity. Hence, authorities are privatizing, commercializing and commoditizing nature at an alarming rate through payment for ecosystem services to wildlife derivatives. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), a multilateral treaty set up at the 1992 UN Earth Summit has a target the protection of 17 percent of terrestrial and inland water and 10 percent of coastal and marine areas. For instance, Conservation International (CI) pushed the government of Madagascar to protect 10 percent of its territory, while in Mozambique a British company negotiated a lease with the government for 19 percent of the country’s land. President Elizabeth Sirleaf Johnson of Liberia called for the extradition of a British businessman accused of bribery over a $2.2 billion carbon offsetting deal. The deal was to lease one-fifth of Liberia’s forests, which account for 32 percent of its land. In Uganda, a Norwegian company leased land for a carbon sink project, which evicted 8,000 people in 13 villages.

In Oxfam Australia’s 2016 report on land grabs, palm oil has become “responsible for large-scale deforestation, extensive carbon emissions and the critical endangerment of species… India, China and the European Union (EU) are the largest consumers of palm oil globally.” The European Union’s renewable energy policy being a significant driver of global palm oil demand due to its aim to source 10 percent of transport energy from renewable sources by 2020, which has increased its palm oil usage by 365 percent.

Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) is an effort to create a financial value for the carbon that is stored in forests. It is used to justify green grabbing and is expected to be one of the biggest land grabs in history. By using REDD+ as a conservation mechanism and a financial stream, “the CDB is both legitimating the commodity of carbon itself and helping to create the market for its trade.” The CDB is forming new nature markets along with new nature derivatives whereby investors speculate on future values encompassed in, for instance, species extinction like that of tigers.

Financial Fragility

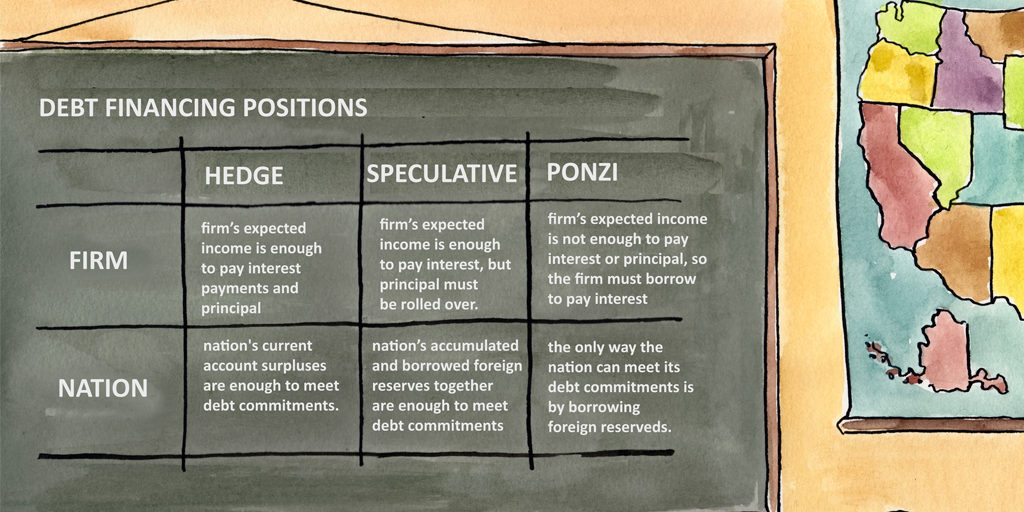

Hyman Minsky was fully aware that a capitalist system was a monetary system with financial institutions that were prone to instability. Minsky is famous for saying that the strength of capitalism is that it comes in at least 57 varieties. The last and current stage is Money Manager Capitalism, which was made up off highly levered profit- seeking organizations like that of money market mutual funds, mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds, and private pension funds. The financial instability hypothesis argues that the internal dynamics of capitalist economies over time give rise to financial structures, which are prone to debt deflations, the collapse of asset values, and deep depressions. Minsky has always warned, “Stability is Destabilizing.”

Money managers act as agents. They pursue short-term profits by trading instruments that are not easily verifiable, which makes fraud likely possible in carbon markets. The dramatic rise in securitization has opened up national boundaries leading to the internationalization of finance. Securitization within the carbon markets increases the risk of leading to boom-bust cycles. At present, speculators are the major players in carbon trading and their dominance in carbon markets is growing at an alarming rate. Financialization is an important precondition for the rise and operation of carbon offsets. The financial innovation in this scheme is that it uses nature itself as a financial instrument. Moreover, it is selling nature to save it and then saving nature to trade it.

‘Green bonds’ are carbon assets that are sold to the Northern hemisphere, backed by Southern land and Southern public funds. Lohmann shares that financial speculation of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) are at least based on specifiable mortgages on actual houses while climate commodity or subprime carbon cannot be specified, quantified, or verified even in principle. Even conservatives and Republicans have said, “if you like credit default swaps, you’re going to love carbon derivatives.” It has become apparent that carbon markets are not only driven by trade, but also by speculation. Carbon derivatives are growing at a fast rate as speculators are moving from other assets towards carbon. Whereas once investors bet on the collapse of the US housing market, there are some traders who are betting on the collapse of the carbon credit market.

As more investors, specifically hedge funds, enter the carbon markets, they increase market volatility and create an asset bubble or ‘carbon bubble’. Money managers by acting as agents trade carbons and increase financial fragility. Their income is driven by assets under management and short-term rates of return. Hence if they miss the benchmark, they will lose their clients. So they act on short profit bases by taking risky positions, and carbon trading provides those risks. In brief, using Minsky’s theory, we can predict with confidence that the carbon market is inherently unstable and that in addition to its not achieving its goal of reducing emissions, it is also heading to a financial disaster.

Even though Minsky pushed for regulation when it came to financial markets, regulating carbon markets will not solve the problem. Tighter regulation of carbon markets, particularly secondary and derivative markets is just a Band-Aid solution and will fail to affect fundamental change. Financial markets have had to be bailed out again and again. However, as a British Climate Camp activist said “nature doesn’t do bailouts.” On a global scale, GHG emissions have gone up. There is an offshoring of emissions. The best policy would be eliminating offsets, specifically from the developing world. Furthermore, there needs to be policies that encourage low-carbon technology as used in Sweden. Another policy recommendations would be a harmonized carbon tax.

Written by Mariamawit F. Tadesse

Illustrations by Heske van Doornen