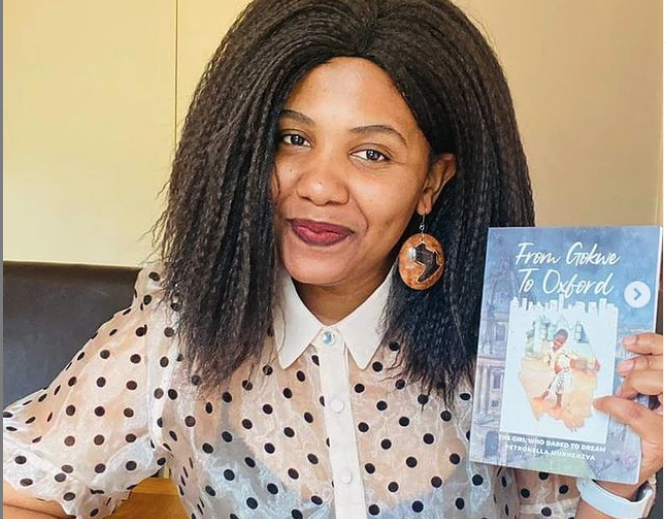

Every so often, we highlight one of the members of the YSI community to share their story and aspirations. Today we cover Petronella Munhenzva, coordinator of the Africa Working Group. This year, Petronella is launching not just a book but also a foundation to support students in Gokwe (Zimbabwe) where she grew up. We talked to her about her hopes, dreams, and where she got the courage to dream.

What led you to decide to write From Gokwe to Oxford?

During my first couple of weeks at Oxford, an American girl came up to me and asked me where I was from. So I told her I’m from Zimbabwe and immediately she went “oh, from Harare I guess?” When I told her no, she thought that was very impressive. The whole interaction was a bit odd to me, but I didn’t think too much of it.

But then those conversations kept on repeating. It turned out I was the only black graduate student at my college, and every time I got questions about my background, everyone was taken aback. They thought I must be a princess. Or a diplomat’s daughter who went to private school in the US.

So I realized I had a choice to make. One option was to go along with the expectations that people had and walk around like an African princess. And I wouldn’t be the first! I know people who tweak their accent and might even lie about what their parents do. But it wouldn’t be the truth, and it would deny the fact that there is real talent and potential in places like Gokwe. It would perpetuate the divide between those who have resources and those who don’t.

So I decided to embrace my story and explain that YES, someone who went to school in a forgotten part of Zimbabwe can go straight to Oxford. Because guess what? People there are smart and talented, too! Both the people at Oxford and the people in Gokwe should realize that.

Tell us about the foundation.

I realized the book would be a starting point; a way to rekindle hopes and dreams. But real resources are needed, too. Gokwe is one of the least developed areas in Zimbabwe. Leaking roofs. Potholes in the road. No money for school. I was there again in December and talked with some of my friends that I met growing up and went to school with. And we just reflected on this sense that most people can never get out of there. So the first thing to do is to believe that things can get better; that’s what the book is for. The second thing is to make them better; that’s where the foundation comes in.

My long term vision is to pay for as many kids’ school fees as possible. And it doesn’t take much! I went to six different schools in Gokwe and guess how much the most expensive one was? 15 US dollars per term. Same with uniforms. They’re made of fabric that’s about 80 cents a meter, so with three dollars you have a uniform. So I want to make sure children stay in school, they have the basic materials they need, and give them access to projects that can develop their talents.

These are simple things. But they make the biggest difference in the world. Once, when I was working as a substitute teacher at my old school, we took a few students for a football tournament. And in our area, all the roads would be gravel with potholes everywhere – just terrible infrastructure. But when we got to a tarred road, one of my students suddenly started screaming. He was just SO excited to play football at a better facility for once. It looked like it was the best day of his life. But that was it. After one fun day everyone goes back home and the cycle continues.

And this keeps their dreams very limited. If you ask a Gokwe student what they want to be when they grow up, many of them just laugh. They don’t even know what you’re talking about! All they know is that when they grow up, they’re going to farm. Like their parents, with their cattle, have their crops. And there’s nothing wrong with being a farmer! But it should be a choice – not the only option.

But when you were little, there was no Petronella to help you! Who was your source of encouragement and support?

My parents – they are the best people in the world. We never really had much growing up but my dad Ronald was a high school teacher at a Gokwe school, and he was always talking about how important education is. He would make sure that you studied. He understood the value of education and working hard. He made sure you got your homework done. And he was extremely supportive of my dreams.

I remember one time when I was in primary school, my teacher told him I’d been doing well at English. So he picked up on that and started telling me I could become an English major! But he didn’t just say that. He started calling me “his English major.” And then when I got older, I wanted to become a lawyer. And he responded by calling me advocate. I was his “Advocate P!”. Then at another instance I decided I would apply for an exchange program with Sweden and after telling him about it, guess what he called me? Sister Sweden! And when I said I’d apply to Oxford? His Oxford Grad. Every time, he crystalized my dreams for me, and made them real before I’d even started. It’s a superpower.

October 2021 will bring not only the publication of From Gokwe to Oxford but also the launch of the Petronella Munhenzva Foundation. Learn more and become a supporter here or contribute via the GoFundMe campaign.