Rob Johnson, President of the Institute for New Economic Thinking, is not your average economist. He’s got heart and soul, or if you’ll have it, the blues! With his deep connection to the arts and humanities, Rob leads the new economic thinking not just with a sharp mind, but also with sensibility.

This article is part of an ongoing series in which Rob shares his life experiences, and biggest lessons learned. If you’re an aspiring expert in economics or a related field, this is for you. It might mitigate the depth and duration of your mid-life crisis. Earlier articles in this series can be found here.

9 – On Reviving the Arts

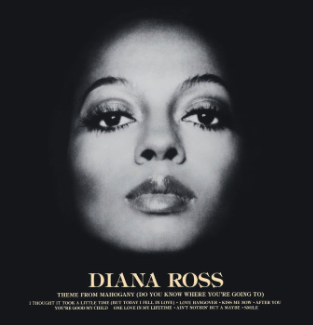

When I left the hedge fund industry and started working in music, I walked into a different world.

Right after acquiring a label, I got together with one of the artists in Chicago. I said, hey there’s no proper contract here, let’s set this up. So he said “well listen to me play this set and come to the stage and we’ll talk.” So I came up with a contract; it basically said he’d get a check for three thousand dollars advance, and then royalties quarterly. And he goes “you see that A.T.M? I will play this next set, and you will pull out three hundred dollars. You don’t have to be doing this in his contract, because nobody ever pays that stuff anyway.” That was a surprise; in the hedge fund industry, I used to trade five hundred million dollars based on word, and now this!

The thing I loved most, by far, was being a producer in the studio–because of the emotional context. When people play music, they can be very vibrant, free and creative. But when they are recording music, that doesn’t always come out. Often there is a dread to be putting down something that people can hear for all time. There’s a fear around that. So as a producer, the question is how do you get past that? How do you unleash the genius that’s within them? I wanted to help them realize that which they’d be most proud of. But I had to get them into the right state of mind. They had to feel that there was no downside to really go for it. That’s hard to do, but I found creative ways.

With this one artist, while we were in the studio, his ex-wife called him and he got in a fight. He was really pissed and he just kept on talking to her. I was getting annoyed because I was paying $400/hour for the studio while he was fighting. But he had a song called “I Gave You What You Wanted, Too Damn Bad You Didn’t Like What You Got” which was about them splitting up. So I said “I think we gotta try I Gave You What You Wanted” tonight, and everybody started grinning. When he took the mic it was like a leopard came out; he just crushed it.

Other times, we’d be in a juke joint, doing a performance and I’d be keeping an eye out for songs to be recorded live. I knew if the band leader had a certain fondness for a lady in the audience. So sometimes, rather than going up and asking him if he would play a certain song, I’d write it on a piece of paper and give it to her, so she could ask him to do it. That worked! He played with so much more passion because it wasn’t me, the producer, coercing him. It was the people he wanted to energize who came with the request.

So in that environment, the currency of motivation was different than logic. Music is an expression of the spirit; it’s not quite as literal as math and models and sense of proportion and all those other things. I think both are valuable. Your question is just in what place do you employ which methods to get the results you’re looking for.

Later on, music also opened a door to documentary film. It started because PBS wanted to make a series on the Blues. Martin Scorsese was involved and he hired a man named Alex Gibney to run with it. At that point, Bob Dylan’s manager, Jeff Rosen, who is a good friend of mine, told me about the series because I had a number of blues artists that were active that could be featured. So, Jeff made sure Alex and I got together.

Not only did we end up working together for the series, but over time we really developed a kinship. I ended up moving my offices in with his offices and started working on documentary film. About this time was the Iraq War and the notion of financial issues. He was making a movie called Enron The Smartest Guys in the Room based on a very well known book. I could advise him because I knew some of the stories about how Enron was discovered; one of the members of INET’s Global Partners Council was one of the short sellers who’d seen it coming.

Then, Alex and I got interested in this torture film. The journalist Bill Moyers used to work with Alex’s father, and I knew Bill very well. There was this group called the Democracy Alliance and Bill and I had talked about torture. Alex’s father had been an interrogator not using torture under General Douglas MacArthur after the Japanese were apprehended, so he was very interested. I went out, put some money in, got some money from other people, and we built a film called Taxi to the Dark Side. It won the Oscar for best feature documentary for 2007! It was a very grim film, obviously. We used to tease each other and say, you know, you come home, you say to your wife, “hey, honey, let’s get some sushi, go to the torture movie!”

I learned a lot about film editing, camera work, and story development from Alex Gibney and his team; it was great. But in the meantime, the global economy was headed for a cliff…

Earlier articles in this series can be found here.

Subscribe to receive the next article directly to your inbox! And in the meantime, take a look at Rob’s podcast Economics and Beyond, available wherever you get your podcasts.