By Daniel Olah and Viktor Varpalotai.

An old myth

Moderate labor costs serve as the basis for the international economic success of a country – this has been the approach favored by policymakers and academicians since the eighties. Still today, most analyses and definitions of competitiveness refer primarily to cost and price factors since these are easy to measure. If you keep your wages down, foreign capital will find you – as the overly simplistic approach suggests, which is a very dangerous narrative.

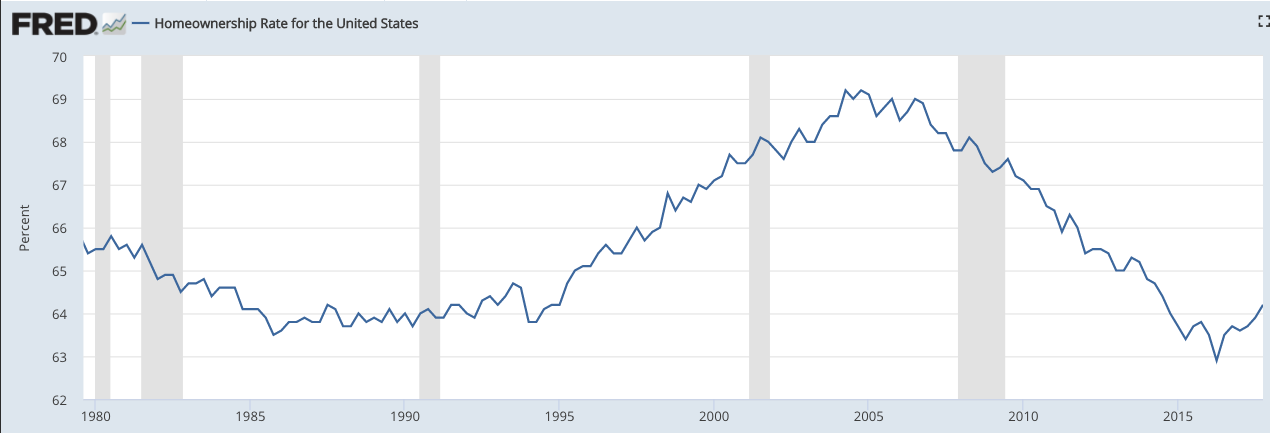

Countries on the peripheries of the richer Western economies often tried to follow this path and it may indeed have been a crucial step towards attracting the much needed capital inflow into developing economies. Think of post-socialist countries which had to achieve what no one managed to do before: to transform their economies from a centrally planned one into a well-functioning market economy in just a few years without an adequate amount of capital, savings, technology, and know-how. A typical win-win situation: developing countries were offered a chance to integrate into global value chains, while companies outsourced production processes with low added value into these economies.

But there is a crucial problem with that: this is just the first period of childhood. To say so, the role of a low-wage model in an economy is similar to that of parents in human life: it is difficult to grow up without them in a healthy way, but once you are an adult you have to realize that you need to live your own life. This means commitment and efforts to move out from the parental nest. Although the low-wage model may be needed to grow up and acquire the potential for an own future life, every economy should move on. But this depends on willingness and ability as well since nothing comes for free. Becoming a successful adult is the most challenging transformation of our lives.

This story is exactly about being able to overcome the low-wage model. When the economy is growing in its childhood period it is key for economic development, but once it turns 18 it suddenly becomes an obstacle to it. The low-wage model conserves inefficient production methods and means no incentive for companies to innovate and invest in the future. A low-wage model is never truly competitive in the long-term: it is a necessary evil in the development process. Nicholas Kaldor already showed this decades ago.

It’s nothing new: Nicholas Kaldor already said that

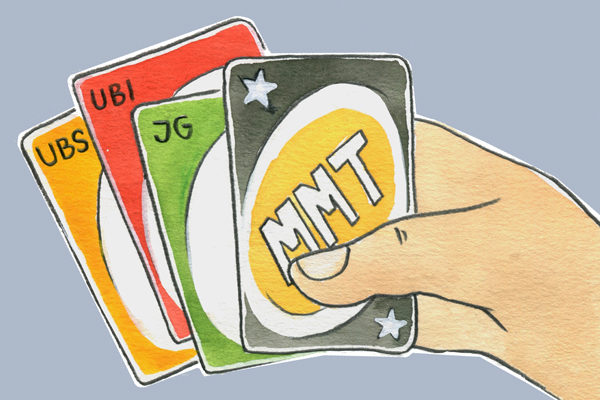

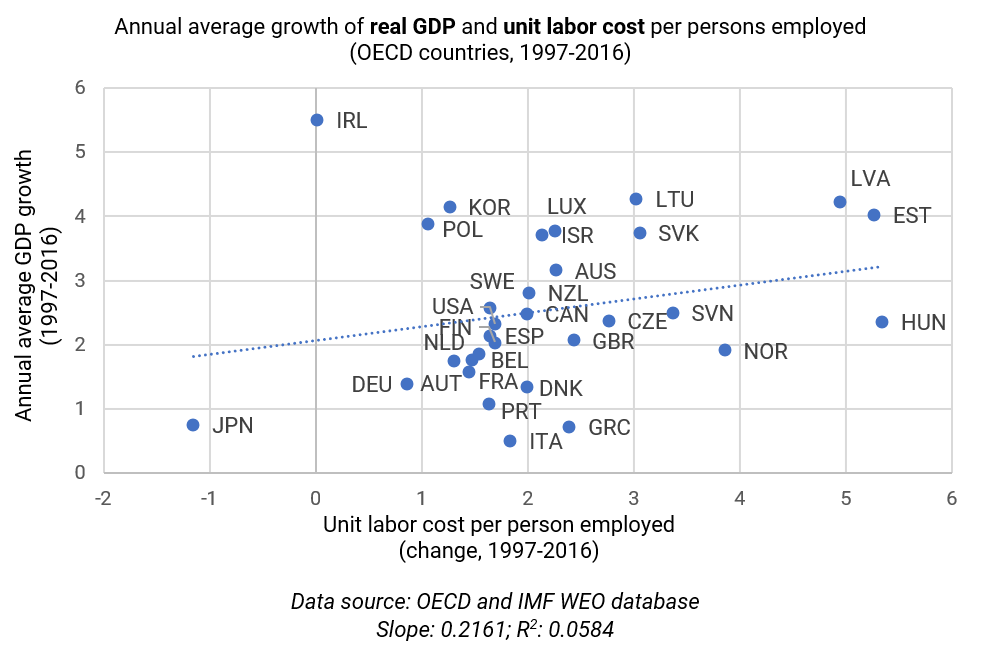

Kaldor, the famous Hungarian economist of Cambridge University, claimed in 1978 that countries with the most dynamic economic growth tended to record the fastest growth in labor costs as well. The renown “Kaldor-paradox” may be confusing for policymakers influenced by the neoclassical mainstream. It tells us that keeping costs low may not lead to competitive advantages and faster economic growth. So let’s resurrect the Kaldorian ideas and see whether the relationship has changed at all (hint: it has not).

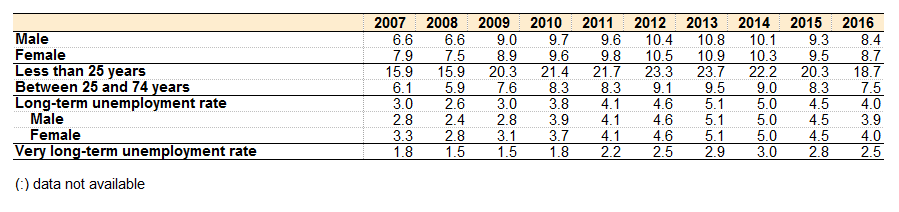

An Econ 101 course would tell us that there is no causality here, and it’s true. But another thing is valid as well: that average annual real GDP growth and the annual growth of unit labor costs per person employed are not negatively related in developed countries.

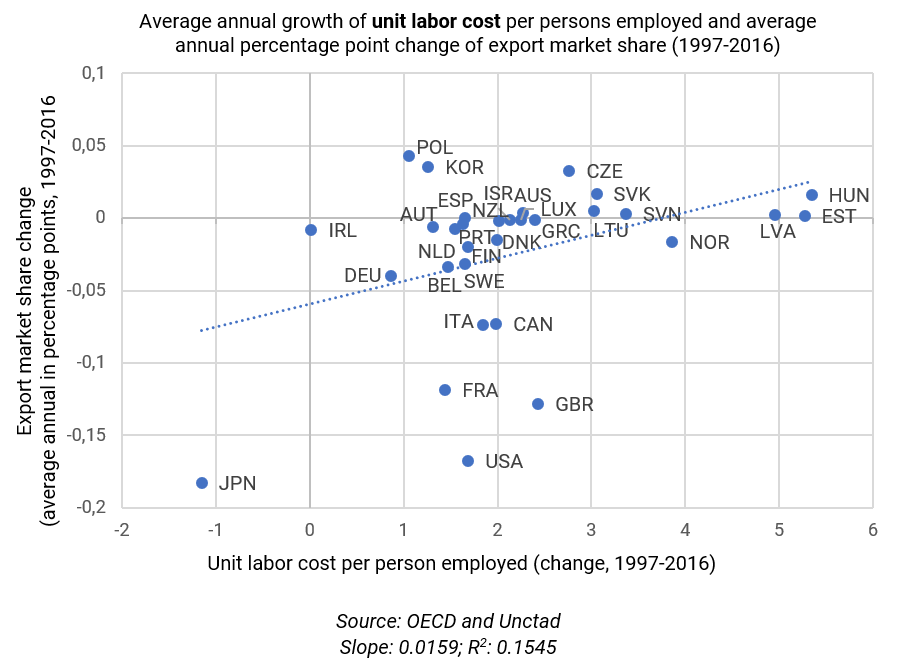

But let’s examine an even better measure, the export share of an economy, which is the best indicator to grasp export competitiveness in an international context. It shows us that in the case of OECD countries it is hard to find a negative relationship between unit labor costs and export market shares. (If we created two groups of OECD countries based on GDP per capita in international dollars we would find no relationship in case of the richer but strong positive relationship for the poorer countries.)

Increasing labor costs: a sign of economic success?

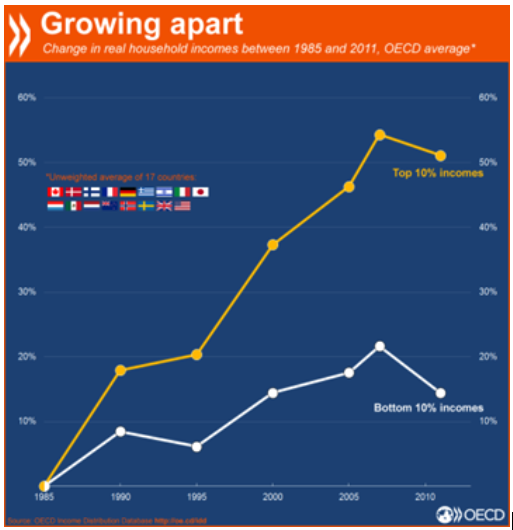

In fact, outside the pure neoclassical framework, the Kaldor-paradox is not a paradox anymore. A wide literature suggests that increasing real wages result in higher productivity: better quality of customer service, lower incidence of absences and higher discipline inside companies. Corporations gain on increasing labor productivity thanks to better housing, nutrition and education opportunities for workers. It is no coincidence that increasing wages improve mental performance and self-discipline as well (Wolfers & Zilinsky, 2015).

As for the companies, a main mechanism for adapting to increasing wages is to improve management and production processes and bring forward new investments. What is more: the often extremely large costs of fluctuation and that of recruiting workers may also be greatly reduced. And finally, the most important aspect: the increase of wages result in greater capacity utilization on the supply side, which results in growing capital stock in the economy (Palley, 2017). Could the Kaldor-paradox imply that most of the examined countries are wage-led (or demand-led) economies?

Several empirical results validate that export-competitiveness is nothing to do with depressed labor costs. Fagerberg (1988) analyzed 15 OECD countries between 1961 and 1983 – more thoroughly than this article does – and found the same results. He states that technological and capacity factors are the primary determinants of export competitiveness instead of prices. Fagerberg (1988) argues that the Japanese export successes are due to technology, capacity, and investments while the US and the UK lost market shares because they allocated resources from investing into production capabilities towards the military.

Storm and Nasteepad (2014) argues that the German recovery from the crisis is not primarily due to depressed wages but to corporatist economic policy, the key reason which focuses shared attention of capital, labor and government towards the development of industry and technology. As for Central-Europe, the case is the same: Bierut and Kuziemska-Pawlak (2016) finds that the doubling of Central-European export share is due to technology and institutions, and not due the cost of labor. In fact, unprecedented wage growth and dynamic export increases go hand in hand in many Central European countries nowadays.

And if we consider the new approach to competitiveness by Harvard-researchers then we come to the conclusion that economic complexity instead of wages is the key driver of future economic and export growth. Their competitiveness ranking seems much different from the traditional measure of the World Economic Forum, having the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Hungary and the Slovak Republic among the first 15 countries in the world. This shows that peripheric countries of the developed West may become deeply embedded in global value chains, becoming more and more organically complex and this complexity of their economic ecosystem has the potential for future growth – even despite forty years of communism.

This evidence shows that policymakers should be careful and conscious. Economic relationships or the adequate economic policy approaches may change faster than we think. Economies are just like children: they grow up so fast that we hardly notice it. That is what the stickiness of theories is about.

About the authors:

Daniel Olah is an Economics editor, writer and PhD student.

Viktor Varpalotai is the Deputy Head of Macroeconomic Policy Department at the Ministry of Finance, Hungary.