We are so honored to introduce to you our new YSI working group coordinators! Three for each working group, this global group of 63 is stepping in to serve the working groups for a two year term. Get to know them!

Written by Mariana Campos Pastrana

Africa

Herbert Mba Aki | Herbert Mba Aki began his career studying law and joined YSI without a background in economics. He joined with the intention to learn about topics in macroeconomics, political economy, and development policies to support his PhD research in Political Science. In 2019, he attended his first YSI event which left him inspired after meeting bright and talented Africans who had careers as entrepreneurs, activists, artists, and policy-makers. Herbert decided to increase his involvement in YSI and saw the Africa Working Group as a space to not only make changes in his academic framework but where he could pose questions and solutions for the economic challenges faced by the region. He now serves as coordinator for the Africa Working Group.

Petronella Munhenzva | Africa Working Group coordinator, Petronella Munhenzva, grew up in a remote area in Zimbabwe that lacked government resources and access to development. This inspired Petronella to explore the impact of state policies on people’s livelihoods on a local level. Petronella sees access to opportunities and recognition as a challenge faced by African scholars, and also notices that a lot of the theories and concepts that are used to explore African topics tend to be imported from abroad. It is very important to support local knowledge and to support the works of African scholars, which Petronella works hard to do.

Geraldine Sibanda | Geraldine Sibanda first joined YSI three years ago after speaking at a panel at the YSI Africa convening in Zimbabwe and considers the Africa working group her home within YSI. She sees a challenge for the economic field in the region to be that there is little progress made into “unpacking and understanding unique country-specific and region-specific problems and creating tailor-made solutions for them.” Geraldine is currently based at the University of the Free State in South Africa.

Behavior and Society

Leigh Caldwell | Early in his economics career, Leigh Caldwell was building models of human and organizational knowledge while writing software – but he soon realized the implicit rationality assumptions he was relying on were, well, nonsense. He decided to start looking at principal-agent problems that were tied to accuracy. When presenting his insights at a workshop, he was introduced to behavioral economics literature and he realized there was a rich source of material which shined a light on the problems he’d been looking to solve. Today, Leigh serves as one of the coordinators for the Behavior and Society Working Group!

Komal Shakeel | Komal Shakeel has been a part of YSI since our beginning in 2013 and was part of the group that created the founding principles. Back then, working groups were based on regions and she set up a working group of China and Pakistan. Eventually, she realized that this approach was too broad for her interest area. Komal wanted to support and to connect with researchers around the world who were interested in behavioral economics and so the Euro-Economics Working Group was born, which eventually evolved to the Behavior and Society Working Group. She now serves as coordinator for the group.

Iva Parvanova | Iva Parvanova is a Bulgarian researcher currently based at LSE in London. A YSI member since 2016, Iva is one of the new coordinators for the Behavior and Society Working Group. Her research interests are rooted in behavioral and experimental approaches applied to understand corruption in healthcare. A dedicated researcher on this topic, the book currently sitting on her nightstand is “Doing Harm: The Truth About How Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Dismissed, Misdiagnosed, and Sick” by Maya Dusenbery.

Complexity Economics

Rutuja Uttawar | Meet Rutuja Uttawar! Rutuja was first introduced to economics when she stumbled on “The Economic Naturalist” by Robert H. Frank, which led her to the world of Heterodox economics and eventually led her to complexity as an approach to economic thinking. She was introduced to the Complexity Economics Working Group after submitting an abstract for the Festival for New Economic Thinking in Edinburgh in 2017. She then joined as a member and organized a reading group and now serves as one of the newest coordinators for the Complexity Economics Working Group.

Vanessa de Lima Avanci | Vanessa de Lima Avanci is currently based at Ideies in Vitória, Brazil and is a coordinator for the Complexity Economics Working Group. She first became acquainted with YSI in 2017 after attending the Innovation Bootcamp in Tallin, and later attended the Latin America convening in Buenos Aires the following year as part of the Complexity Economics Working Group.

Solomon Owusu | Solomon joined YSI and the Complexity Economics Working Group after being introduced by his friend, Danilo, in 2017. The group has been able to organize many projects and been able to build a strong, open, and transparent community. As coordinator, Solomon is excited to increase activity for the working group with more webinars, research groups and reading groups!

Cooperatives

Emi Do | Meet Emi Do, one of the coordinators for the Cooperatives Working Group who is currently based at the Tokyo University of Agriculture in Japan. Emi challenges herself not only through academia but also through trail running. She views this challenging endeavor as an excellent contrast to the arduous nature of academia. Her longest distance so far has been 115km and she’s hoping to complete a 100 miler within the next year!

Terence Tapiwa Muzorewa | Coordinator Terence Tapiwa Muzorewa first joined YSI in 2017 after attending a conference at the Free State University in South Africa. Terence admits that he fell in love with the working group! However, he has been working on cooperatives since before joining the working group and studied housing cooperatives for his PhD. Terrence is based at Midlands State University in Zimbabwe.

East Asia

Soheon Lee | Soheon Lee is one of the coordinators for the East Asia Working Group and is currently based at the Korean Embassy in Japan. Soheon first became a member of YSI in 2015 and has been actively participating as part of YSI. She joined the East Asia Working Group when it was re-established in 2017 to connect with Asia-based researchers and has met great colleges, young scholars and mentors through the working group and looks forward to meeting more!

Seung Woo Kim | Seung Woo Kim’s journey to becoming one of the coordinators for the East Asia Working Group began towards the end of his Ph.D. Seung Woo became interested in the global turn in economic history, which highlighted the problematic aspect of the Eurocentric view of the discipline. This pushed Seung Woo to research the way in which the Global South engaged in global finance and the international monetary systems as well as alternative approaches to economics. He then found the East Asia Working Group to be a space in which he could pursue various of these topics.

Rachel Ganly | Rachel Ganly is a MPhil Student in the Division of Social Science at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Her work explores the effect of men’s long working hours and gendered work norms on family formation in East Asia, supervised by Stuart Gietel-Basten.

Economic Development

Surbhi Kesar | Meet Surbhi Kesar, coordinator for the Economic Development Working group and a crime fiction fan! Based at Azim Premji University in Bengaluru, India, Surbhi believes that research agendas need to be global in its outlook and local in its reach. Her vision for the working group is for members to play the role of community researchers who can engage with questions of development, especially now with the challenges brought on by COVID-19.

Nurlan Jahangirli | Nurlan’s interest in Economic Development stems from his childhood in Baku, Azerbaijan. He noticed the economic struggles of the regions and from a young age held the belief that he wanted to contribute to the development of the region. This belief eventually led him to economics, and after a series of adventures, he committed to the area of development. Through the current COVID-19 crisis, Nurlan has seen how fragile economies are with regard to health crises and social problems. Because of this, he sees it as important to reframe how we view the development process. Nurlan is currently based at the University of Hamburg in Germany.

Santiago Gahn | Meet Santiago, an Argentine scholar based at Roma Tré University. He is a guitar aficionado, who favors the Blues and Jazz, and also a keen songwriter. He cites Jimi Hendrix as his biggest inspiration. He is currently working on “Towards a Theory of Economic Development” as there is currently no standardized theory of Economic Development. He sees it as important to read classical economic theories from theorists such as Adam Smith and Karl Marx and to interpret them through modern classical theory.

Economics of Innovation

Fernanda Steiner Perin | Fernanda first joined the Economics of Innovation Working Group at the Latin American convening in Buenos Aires in 2018. She later became an organizer as part of the Latin America Working Group and worked on projects related to innovation, which has led her to become a coordinator for the Economics of Innovation Working Group! With the current global situation as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, Fernanda sees a stronger need for innovation and policies to support innovation.

Rosie Collington | When Rosie Collington joined Genetic Alliance UK’s Policy and Public Affairs team back in 2016, her role was to develop and communicate responses to policy developments in genomics, health care, and health data to patients. However, it soon became evident research in these areas within political economy and socio-economics was sparse. Rosie decided to dedicate her work to understanding the economics of health data, public sector digitalization, and health innovation and promote it widely.

Dario Vazquez | Meet Economics of Innovation coordinator, Darío Vázquez! When we asked Darío what he believes the largest challenge facing the field is, he responded: “to transform the logic of innovation processes in order to guide them towards solving the great social challenges of our time.” Dario is currently based at the UNSAM in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Economic History

Diego Castañeda | Diego Castañeda takes his economic history talents beyond academia. The new coordinator for the Economic History Working Group hosts “Mancha,” a radio show which debates politics, economics, and public life (you can listen on NoFm-radio.com!) He’s also currently producing a podcast on the economic history of pandemics and covers various different eras, from the Antonine plague that ravaged the Roman Empire to the current COVID-19 crisis.

Maylis Avaro | Meet Maylis Avaro! She is a French scholar currently based at the Graduate Institute in Geneva and one of the new coordinators for the Economic History group. She has been a member of the working group since 2018 when she first participated at the World Economic History Congress in Boston.

Alain Naef | Say hello to Economic History Working Group coordinator, Alain Naef! He is currently based at UC Berkeley in the USA. As coordinator he finds it important to keep a balance in the group between quantitative and qualitative economic history.

Finance, Law, and Economics

Luisa Scarcella | Say hello Luisa Scarcella! Luisa has been a part of YSI since our early days and attended our first plenary in Budapest. She is the new coordinator for the Finance, Law, and Economics Working Group. As coordinator, she places strong importance in keeping the group representative of the different areas of interest that exist within law and economics. She looks forward to fostering a strong online community that remains tight-knit through the current crisis until it is safe to meet in person again.

Christina Refhilwe Mosalagae| Finance, Law, and Economics Working Group coordinator, Christina’s desire to build a better world began in her early days. Christina cites her Setswana mother and her Polish stepfather as her biggest inspiration. “Through their love, sacrifice, and an appreciation for different cultures, they modeled the type of world that I want to be a part of building.” Christina is currently pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Turin in Italy.

Limia Trifena | Meet Limia Trifena, one of the coordinators for the Finance, Law, and Economics and a boxing enthusiast! Limia first joined YSI two years ago after meeting YSI members at a conference in Berlin. Since this chance encounter, Limia has been an active member of YSI. She is currently based at the University of Warwick in the UK.

Financial Stability

Nathalie Marins | Meet Nathalie Marins! She is based at the University of Campinas in Campinas, Brazil. Nathalie is the newest coordinator for the Financial Stability Working Group, but comes with 11 years of experience in the field of financial stability!

Ádám Kerényi | We asked Ádám Kerényi what is the biggest challenge the Financial Stability Working Group now faces. For him, it’s the COVID-19 pandemic which has not only caused a tragic health crisis and triggered an economic downturn, but a liquidity and solvency crisis as well. These massive challenges to the financial system affect global financial stability. Ádám points out that central banks have remained crucial in safeguarding the stability of global financial markets and maintaining a flow of credit. He sees a need for continued international coordination to observe data, support vulnerable communities, and to contain stability risks.

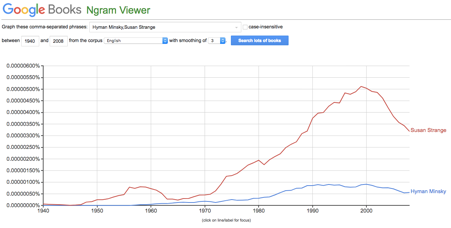

Nicole Toftum | Nicole Toftum decided at the young age of 15 that she would pursue a career in the social sciences. Although she began her undergraduate years focused on politics, she later discovered Minsky and became fascinated with financial issues. She decided to focus on a multidisciplinary MA. During the 2018 YSI Latin America convening, she discovered the Financial Stability Working Group and joined right away and now serves as coordinator for the working group.

Gender and Economics

Magali Brosio | Magali Brosio first discovered the field of gender and economics when studying for her master’s while scrolling through Twitter. This inspired her to write her dissertation on the gender wage gap. Ever since then, her research interests have been within the field of gender and economics – both inside and outside academia. A proud feminist, Magali is one of the newest coordinators for the Gender and Economics Working Group.

Shakatakshi Gupta | Coordinator Shatakshi has always been interested in gender inequality issues, partially stemming from her own experiences with gender discrimination. Studying gender bias issues for her Ph.D., she realized that very few universities considered gender and economics a serious subject area and that there is a lack of coverage of the topic. Shatakshi believes that even though more people are acknowledging the role of economists in inhibiting gender discrimination, there is still a lot of work to be done.

Cicero Braga | Meet Cicero Braga, coordinator for the Gender and Economics Working Group. According to Cicero, the biggest issue facing the field is that there is limited literature on the topic. More data and mechanisms are needed to deal with the issues. Cicero is currently based at the University of Viçosa in Brazil.

History of Economic Thought

Christina Laskaridis | SOAS Ph.D. researcher, Christina Laskaridis, is a new coordinator of the History of Economic Thought Working Group. For Christina, one of the issues facing the niche field is the lack of programs that allow substantial research on the topic. “We are a small field that has been gradually cast out from many Economics departments, and links to adjacent fields are loose.” According to Christina, this creates a challenge in securing Ph.D. programs for newcomers and a lack of career opportunities which would help push the field forward. The History of Economic Thought Working Group is a great place to get started for those interested in doing research within the field.

Julia Marchevsky | Julia first became interested in the history of economic thought while pursuing her undergraduate degree. She started questioning when it was that the world began to focus on the concept of accumulating wealth and her curiosity led her to her current research interests. Christina also notes the importance of the field as she believes that understanding the progression of economic thought allows for those in the field to be better economists. Julia Marchevsky is currently based at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Brazil.

Marius Kuster | Meet Marius Kuster, coordinator for the History of Economic Thought Working Group. The Swiss researcher is based at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland. When we asked Marius one of his secret hobbies, he told us he enjoys making music on his computer!

Inequality

Maria Cristina Góes | Meet Maria Cristina Góes! Maria was first inspired to research inequality while writing her master thesis which was inspired by Michel Kalecki’s theories. Kaleckian models explore how changes in the share of income that goes to workers can impact economic activity and employment by analyzing responses from employers and workers. Maria is the new coordinator for the Inequality Working Group and is based at Roma Tre University in Italy.

Natassia Nascimento | Meet coordinator, Natassia Nascimento! She is a Brazilian researcher currently based at UFRJ in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil! Natassia lists two fellow Brazilians as her biggest inspirations. The first is her grandmother who Natassia admires for her courage and wisdom. The second is Formula 1 legend Ayrton Senna, who was not only the best at what he did but passionate about it too.

Francisco Ardila | Francisco Ardila notes that interest in inequality skyrocketed after the 2008 financial crisis but peaked in 2013 with the release of “Capital in the XXI Century” by Piketty. Francisco notes that interest has become diluted by having inequality often being incorporated into other fields of economics and most research on inequality that is done today is really a by-product of research done in other fields. As coordinator of the Inequality Working Group, Francisco feels that inequality is an important enough subject to merit its own field, front, and center.

Keynesian Economics

Ana Bottega | Say hello to Ana Bottega! Ana first joined the Keynesian Economics Working Group in 2018 at the YSI Latin America Convening in Buenos Aires. She is one of the three new coordinators for the group. Currently on her nightstand? A literary classic – Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. Ana is currently based at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Brazil.

Sylvio Kappes | Meet one of our new coordinators for the Keynesian Working Group, Sylvio Kappes! One of his secret talents is writing fantasy fiction. Sylvio sees that with the current climate, it is crucial that governments do everything possible to end the pandemic; he considers austerity to be a major concern. Sylvio is currently based in Maceió, Brazil.

Lilian Rolim | Lilian Rolim first became involved with the Keynesian Economics Working Group at the Budapest Plenary in 2016 when she met economists working on similar projects. Lilian believes the field needs to adjust to incorporate pressing issues such as climate change and inequality. She also finds it incredibly important for economics to be more inclusive for researchers from diverse backgrounds. Lilian is based at the University of Campinas in Brazil.

Latin America

Gabriel Aidar | For Latin America Working Group coordinator, Gabriel Aidar, one of the biggest challenges he sees is defining the focus of the group. There are many economic topics that are related to the region, but for Gabriel, it is important to create a work plan which allows for the diversity of topics to be pursued while still maintaining focus on the primary issues which the region faces today.

Giuliano Toshiro Yajima | Latin America Working Group coordinator Giuliano Toshiro Yajima hopes to build stronger academic networks within the region. While Latin American research centers and institutions are well connected to their partners in the US or Europe, they have limited ties within the region. For Giuliano, there is a lot of work that needs to be done to strengthen these connections and bolster the research on Latin American economies.

Florencia Jaccoud | Meet yogi and coordinator for the Latin America Working Group, Florencia Jaccoud. Florencia is currently based in Maastricht in the Netherlands at the UNU-MERIT and is originally from Argentina.

Philosophy of Economics

Maisa Ribiero | The philosopher’s role is to question and examine the impact of economic policies and instruments. Philosophy of Economics Working Group coordinator, Maisa Ribiero, gives us an insightful look into how economic philosophers examine economics. One of the focus areas is the tradeoff that comes with economic choices and the impact on human welfare and social justice. Economic reasoning and policies will always impact human welfare and economic philosophers specialize in weighing the ethics of the decisions. They also examine the impact and function of the structures that facilitate economic activity, and they ponder on possible alternatives. For Maisa, the philosopher is a critic of the theories and approaches used by economists. “The most valuable work in science proceeds from the basis of significant expertise on the part of the philosopher”

Merve Burnazoglu | After a visit to her sister’s private banking office in Switzerland, Merve Burnazoglu was fascinated by the connection between the graphs and equations she saw on the screen and how they represented wealth in “the real world”. For Merve, this sparked her curiosity as to how wealth is created or extracted in the real world and this inspired her to study economics. As an economist, she began to further question economic systems and society, which led her to her current research area in Philosophy of Economics.

Juan Melo | For Philosophy of Economics Working Group coordinator, Juan Melo, the biggest challenge economists face is to bridge the gap between “big picture” topics (such as inequality, discrimination, democracy and markets) and the methodological questions, modelling, and theory that economists typically use. The way Juan sees it, Philosophers of Economics have the unique opportunity to use their research to foster exchange between science and political economy, which may be a daunting task, but also a rewarding one.

Political Economic of Europe

Stefano Merlo | Stefano Merlo first became part of the Political Economy of Europe working group after presenting his dissertation at the first YSI Plenary in 2016. At the time, he was researching the account imbalances before the Euro Crisis and many researchers in the working group offered guidance, suggesting that he take a look at the EU as well. Stefano not only heeded their advice, but became more interested in the topic, and is now one of the coordinators for the group!

Salome Topuria | Meet Salome Topuria, one of the coordinators for the Political Economy of Europe Working Group! Her research background is in political economy, and she studied Political Economy of European Integration at the Berlin School of Economics and Law and is currently a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Kassel in Berlin.

Stefano Di Bucchianico | Say hello to Stefano Di Bucchianico, an Italian researcher currently based in the beautiful and historic city of Siena at the University of Siena. Stefano is one of the new coordinators for the Political Economy of Europe Working Group and is excited to set up an established schedule of activities for the group!

South Asia

Aneesha Chitgupi | Aneesha Chitgupi first joined YSI while pursuing her PhD. She wanted to explore organizations that supported and encouraged new ways of research, which led her to a YSI workshop in Kolkata, India where she participated as a YSI panelist. The rest is history and we welcome her as one of the coordinators for the South Asia Working Group.

Arun Balachandran | 24% of the world’s population lives in 3% of the world’s land area in South Asia, as noted by Arun Balachandran, making the density of its population a challenge for the region. Arun points out that most of the major issues in South Asia stem from its demographic composition but its population also has the potential to be a driver for its economic growth. He points out that South Asia has begun to adopt alternative ways of thinking and believes that the spread of people-centric economic development could be the key to the region’s growth. Arun Balachandran is a coordinator for the South Asia Working Group.

Aqdas Afdal | Aqdas Afdal was already an involved member of YSI prior to becoming a coordinator for the South Asia Working Group. He first started attending our events way back in 2015 when YSI was still in its infancy! Aqdas appreciated how the working groups would bring together some of the brightest minds from around the world to generate new ideas for a sustainable, just, and equal world.

States and Markets

Nicolas Aguila | Argentine scholar Nicolás Aguila first became involved with the States and Markets Working Group when the group was first created in 2017, which was also how he was first introduced to YSI. He is currently based in Birmingham, UK.

Esra Urgulu | Esra’s interest in development economics, industrial policy and the role of the state started before she even began studying economics! Over the past few years, she has participated in multiple panels on these topics organized by YSI and the States & Markets Working Group. She is very excited to be one of the group’s new coordinators.

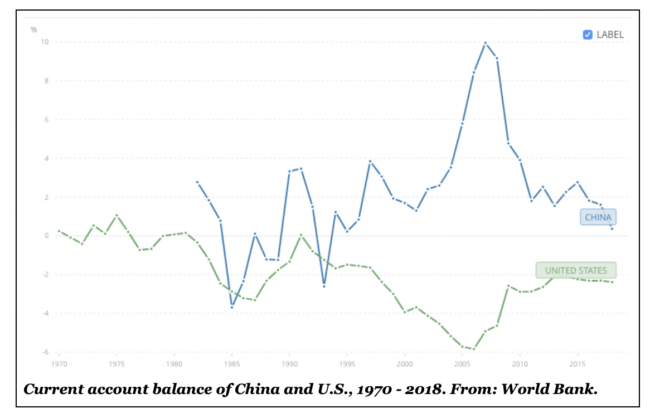

João Macalós | João first fell into his current research topic – quantitative analysis of international monetary relations – during his time as an assistant lecturer. He realized that the field was underdeveloped and eventually discovered the States & Markets Working Group after being introduced by friends and colleagues. The group touched on his research interests and he has been a dedicated member ever since.

Sustainability

Felipe Botelho Tavares | Sustainability is one of the most pressing issues of our time, and according to Sustainability working group coordinator Felipe Botelho Tavares, one of the biggest challenges is working to “re-orient human and economic activities towards new paradigms of prosperity” and also to focus on ensuring a lasting quality of life and environment for future generations to come. Felipe is currently based in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil at the Brazilian Petroleum Institute.

Ariel Ibanez-Choque | Meet Ariel Ibanez-Choque, one of the new coordinators for the Sustainability Working Group! He first became involved with the topic when studying it as part of his master’s degree when he became part of a multidisciplinary and international research team focusing on sustainability and natural resources in Latin America. Ariel is currently based at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana in Mexico City.

Dania Clarke | Say hello to Dania Clarke, one of the newest coordinators for the Sustainability Working Group. Like many Vancouverites, Dania loves tending to her indoor plants and backcountry hiking through British Columbia’s beautiful scenery. She is currently based at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada.

Urban and Regional Economics

Kishorekumar Suryaprakash | “After the advent of neoliberalism, urban inequality has increased. Competition between global cities to attract capital have resulted in a relaxation of labour laws, environmental laws, huge tax concessions and expropriation of poor from their lands. [This has] created a major gulf between the rich and poor in cities” – Kishorekumar Suryaprakash, Urban and Regional Economics Working Group coordinator

Rafael Campos | For Rafael Campos, the Urban and Regional Economics Working Group is able to be a strong player in the exchange of ideas between young scholars around the world largely in part because of its global nature. For Rafael, this is of paramount importance since the group often addresses issues such as the role of geographic space on economic development and having members from diverse locations allows for different experiences and approaches to be heard.

Simone Grabner | We asked Simone Grabner if she had any secret talents and like many of us in quarantine, she has been working on her cooking skills! She is a self-confessed foodie and loves to whip up meals for her family and friends. She is currently based at the Gran Sasso Science Institute in L’Aquila, Italy and has become a keen cook in Italian cuisine! Simone is one of the newest coordinators for the Urban and Regional Economics Working Group.