This is the story of Susan Strange and Hyman Minsky, two renegade economists who spent a lifetime warning of a global financial crisis. When it hit in 2008, a decade after their deaths, only one rocketed to stardom.

By Nat Dyer.

When Lehman Brothers went belly up and the world’s financial markets froze in the great crash of 2008, the profession of economics was thrown into crisis along with the economy. Mainstream, neo-classical economists had largely left finance and debt out of their models. They had assumed that Western financial systems were too sophisticated to fail. It was a catastrophic mistake. The rare economists who had studied financial instability suddenly became gurus. None more so than Hyman Minsky.

Minsky died in 1996 a relatively obscure post-Keynesian academic. He was only mentioned once by The Economist in his lifetime. After 2008, his writings were pored over by economists and included in the standard economics textbooks. Although not a household name, Minsky is today an economic rockstar named checked by the Chair of the Federal Reserve and Governors of the Bank of England. One economist summed it up when he said, “We’re all Minskites now”. The global financial crisis itself is often called a “Minsky moment”. But not all radical economic thinkers were lifted by the same tide.

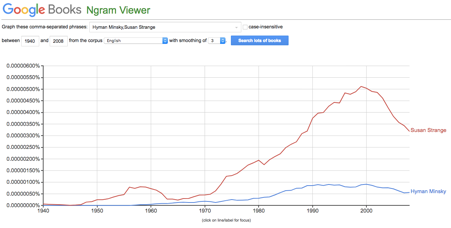

Susan Strange was more well-known than Minsky in her lifetime (see Google ngram graph below). One of the founders of the field of international political economy, she taught for decades at the London School of Economics. Alongside her academic work, she raised six children and wrote books for the general public warning of the growing systemic risks in financial markets. When she died in 1998 The Times, The Guardian and The Independent all published an obituary for this “world-leading thinker”.

The two renegade economic thinkers, although working in different disciplines, had much in common. They both gleefully swam against the tide their entire careers by studying financial instability. They were both outspoken outsiders who preferred to teach economics with words rather than equations and were skeptical of the elegant economic models of the day. They were big thinkers haunted by the shadow of the 1930s Great Depression. They both died a decade before being vindicated by the 2008 financial crisis. And, they read each other’s work.

The New York Times called Susan Strange’s 1986 Casino Capitalism “a polemic in the best sense of the word.” Calling attention to financial innovation and the boom in derivatives, the book argued that, “The Western financial system is rapidly coming to resemble nothing as much as a vast casino.” Minsky, in his review, said that the title was an “apt label” for Western economies. Strange provided a much-needed antidote, he said, to economists “comfortable wearing the blinders of neoclassical theory” by showing that markets cannot work without political authority. He probably liked the part where Strange praised his ideas too.

Casino Capitalism hailed Minsky’s ‘Financial Instability Hypothesis’ way before it was fashionable. Strange singled out Minsky as one of a “rare few who have spent a lifetime trying to teach students about the working of the financial and banking system” and whose ideas might allow us to anticipate and moderate a future financial crisis. Minsky’s concept of ‘money manager capitalism’ has been compared to ‘casino capitalism’.

But, put Susan Strange’s name into Google News today or ask participants at meetings on economics about her and you don’t get much back. They will sometimes recognise her name but not much more. Outside a small group, she’s a historical footnote, better remembered for helping to create a new field than the force or originality of her ideas. It is as if two people tipped the police off about a criminal on the run but only one of them got the reward money.

So, why did Strange’s reputation sink after the global financial crisis when Minsky’s soared?

Professor Anastasia Nesvetailova of City, University of London, one of the few academics who has studied both thinkers, believes it is due, in part, to their academic departments. “Minsky may have been a critical economist but he was still an economist,” she told me. Strange studied economics, but then worked as a financial journalist before helping to create the field of international political economy, now considered – against Strange’s wishes – a sub-discipline of international relations. Economics is simply a more prestigious field in politics, the media and on university campuses, Nesvetailova said, and Minsky benefited from that. “Unfortunately, [Strange] remains that kind of dot in between different places.”

As we live through a political backlash to the 2008 crisis and the IMF warns another one might be on the way, Strange’s broader global political perspective is a bonus. In States and Markets, she sets outs a model for global structural power which brings in finance, production, security and knowledge. Her writings predicted the network of international currency swaps set up by the Federal Reserve after the global financial crisis, according to the only book written about Strange since 2008. Her work foreshadowed the global financial crime wave. And, she argued repeatedly that volatile financial markets and a growing gap between rich and poor would lead to volatile politics and resurgent nationalism, which is embarrassingly relevant today. The financial crisis may have been a ‘Minsky moment’ but we live in Strange times.

This global political economic view explains why Strange criticised Minsky and other post-Keynesians for thinking in “single economy terms”. Most of their models look at the workings of one economy, usually the United States, not how economies are woven together across the world. This allows Strange to consider “contagion”: how financial crises can flow across borders. It’s a more real-world vision of what happens with global finance and national regulation. Her greatest strength, however, also reduced her appeal in some quarters as it means Strange’s work is less easy to model and express in mathematics.

Minsky found fault in Strange too. She should have more squarely based her analysis on Keynes, he said and showed the trade-off between speculation and investment. Tellingly, his critique is at its weakest when engaging with global politics. Strange unfairly blamed the United States for the global financial mess, Minsky wrote, even though it was no longer the premier world power. Minsky was only repeating the conventional view when he wrote that in 1987 but it was bad timing: two years later the Berlin Wall fell ushering in unprecedented US dominance.

In her last, unfinished paper in 1998 Strange was still banging the drum for Minsky’s “nearly-forgotten elaboration of [John Maynard] Keynes’ analysis”. Now it’s her rich and insightful work that is nearly forgotten outside international relations courses. A jewel trodden into the mud. Just as Minsky is read to understand how “economic stability breeds instability”, let’s also read Strange to appreciate her core message that while financial markets are good servants, they are bad masters.

About the author

Nat Dyer is a freelance writer based in London. He has an MSc in International and European Politics from Edinburgh University. He was previously a campaigner with Global Witness, an anti-corruption group. He tweets at @natjdyer.

Google Ngram showing the frequency of references to Susan Strange (red) and Hyman Minsky (blue) from 1940 to 2008

Strange was more referenced in her lifetime than Hyman Minsky. Google Ngram’s search only goes up to 2008. After 2008, we would likely see a hockey stick spike for Minsky and Strange continuing to fall.

Susan Strange’s writings remain highly relevant. See my blog: https://storybookreview.wordpress.com/2011/05/18/jonathan-story-setting-the-parameters-extracts-from-chapter-2-in-strange-power-shaping-the-parameters-of-international-relations-and-international-political-economy-ashgate-publishing-limited/