By Alexander Beunder. Investigative journalist. Platform Authentieke Journalistiek, the Netherlands.

Now that the dust has settled around the latest U.S.-China trade war spat, here’s something the Trump regime may want to evaluate before the next round: the fact that many economists and analysts refused to side with Trump and Mnuchin when they accused China of “currency manipulation”.

Initially, the story of Chinese currency manipulation was echoed around the world, when the Chinese yuan dropped 1,4% to the dollar on Monday, August 5. After US president Donald Trump responded by tweet that China was guilty of “currency manipulation”, the Wall Street Journal and others described how Beijing was “weaponizing the yuan”. China was obviously responding, some analysts said, to new import tariffs on Chinese products which Trump had announced a week before. The press paid even more attention to the story because of the diplomatic drama around it, as US Treasury secretary Steven Mnuchin rushed to officially declare China a “Currency Manipulator” and said to bring the matter to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

It’s an accusation Trump (but before him, Obama) has been repeating for years. China’s central bank is supposedly keeping the value of the yuan to the dollar artificially low – by buying and holding on to dollar reserves – to make its exports cheap for the rest of the world. This creates an “unfair competitive advantage”, in the words of Mnuchin. Thanks to its cunning currency manipulation scheme, the argument goes, China enjoys a persistent trade surplus – exporting more than importing – while the U.S. suffers a trade deficit, hurting businesses and workers.

But fact-checking Trump’s statements has become a healthy habit among journalists. Several analyses quoted economists who disagreed with the latest accusations by Trump and Mnuchin. As The New York Times business correspondent Alexandra Stevenson noted, “many economists believe [China’s] currency should be weakening versus the dollar”, due to slow growth and the trade war with the U.S.. Another source, U.S.-economist Dean Baker, noted the 1,4% drop was large but “not that unusual” and can happen “without government intervention”. Even the annual review of China’s economic policies by the IMF, released after Monday’s accusations, concluded there is no sign of currency manipulation.

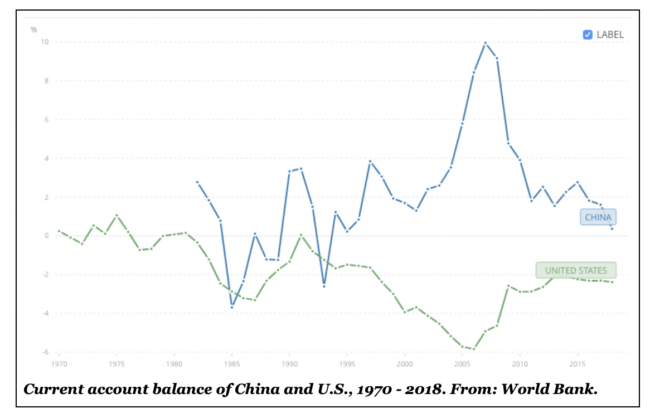

Still, several established correspondents agreed that the accusation was valid in the past. “China kept its currency weak a decade ago”, Stevenson wrote, but the yuan has now “strengthened to a level widely believed to be close to fair value”. Her colleague Eduardo Porter at The New York Times shared a similar view in an article which headlined, “Trump Isn’t Wrong on China Currency Manipulation, Just Late”. Bloomberg correspondent Noah Smith drew the same conclusion, noting China enjoyed a large trade surplus in the 2000s, but the “the country’s current account deficit has largely vanished”, after a peak in 2007.

Flawed economics

However, there may be something more fundamentally wrong with the currency manipulation accusation, and not just with the recent application of it by Trump and Mnuchin.

New York-based economist Anwar Shaikh and London-based economist Isabella Weber have been arguing for several years that the whole currency manipulation argument is based on flawed economics. Shaikh, an economics professor at the New School of Social Research in New York, and Weber, a lecturer in economics at Goldsmiths, University of London, published a working paper on the topic last year titled “Debunking the Currency Manipulation Argument”.

If they’re right, even the belief that China was guilty of currency manipulation a decade ago becomes questionable.

To understand what’s wrong with the currency manipulation argument we have to go back to the underlying trade theories, Shaikh and Weber explain. As currency manipulation can not be observed directly, economists look at other economic phenomena which, according to standard trade theory, are indicators of currency manipulation. A persistent trade surplus is the most important indicator because, according to standard trade theory, free trade would automatically eliminate trade imbalances. Hence, wherever a persistent trade surplus exists, it must be the result of currency manipulation, the argument goes.

The Chinese trade surplus, always positive since 1994, has been the central pillar of the currency manipulation argument, Shaikh and Weber note. Not just for academic economists; the U.S. Treasury uses persistent trade surpluses as official, legal criteria to determine whether a country is guilty of currency manipulation to gain an “unfair competitive advantage”.

But the proof is in the pudding, in this case, standard economic trade theory. If the theory is incorrect – which it is, according to Shaikh and Weber – the whole narrative collapses.

What’s wrong with the trade theory? The theory goes back to a famous model of the British economist David Ricardo (1772-1823), Shaikh and Weber explain. In Ricardo’s model and modernized versions of it, free trade ensures that, over time, no trading partner would enjoy a trade surplus or suffer a trade deficit. Imagine a country which would initially be more competitive in, let’s say, all sectors. Free trade would result in high exports and low imports (a trade surplus) attracting a massive inflow of money from foreign buyers. Such an inflow of money creates domestic inflation or an increase in the exchange rate, damaging competitiveness and eliminating the trade surplus. In a weaker, deficit country the opposite would happen: an outflow of money creates domestic deflation or a drop in the exchange rate, boosting competitiveness and exports and eliminating the trade deficit.

But the theory is fundamentally wrong, Shaikh and Weber argue. The “natural” result of a world in which trading partners enjoy different levels of competitiveness is not balanced trade. The “natural” result of free trade in such a world, they argue, is imbalance – trading partners with persistent trade surpluses and deficits.

Relying on classical economists like Adam Smith (1723 – 1790) and Roy Harrod (1900 – 1978), Shaikh and Weber present their alternative trade theory: in their version, the magical price or exchange-rate movements which would equilibrate trade in Ricardian models won’t happen. For instance, in a surplus country, large inflows of money due to excessive exports will not create domestic inflation or a rise in the exchange rate, because there’s something else that these flows of money do: move back to where they came from. Any oversupply of money a surplus country would receive would initially be saved in local banks and decrease the domestic interest rate. This would push capital towards other countries where it enjoys higher returns – indeed, to the deficit countries where the interest rate has increased due to an outflow of money.

Hence, a likely outcome of free trade is that surplus countries become creditors, and deficit countries become borrowers, and there are no automatic price or exchange-rate movements which would balance trade accounts.

This is, Shaikh and Weber note, an accurate description of the financial relation between the US and China, as China has become the largest creditor of the US. The only peculiarity, they explain, is that China’s public central bank is doing the lending (buying dollar assets) because Chinese capital controls prevent private investors from fulfilling this role. But these operations “might only mimic what would be the outcome of free capital and trade flows”, Shaikh and Weber explain. To label these monetary operations as the main instrument of a cunning currency manipulation scheme, as Mnuchin and others do, is unwarranted in their view.

So, if Shaikh and Weber are right, global imbalances in trade are simply natural outcomes of the free market, not of government interference. And if that’s the case, the currency manipulation arguments holds no water, as “we cannot infer from trade imbalances and from China’s purchase of reserves that the currency has been manipulated”.

No, Shaikh and Weber can’t exclude the possibility that China has intervened in the value of the yuan for purposes of competitiveness. Their main point is that the conventional criteria used by academics and the US Treasury to determine this – trade surpluses and deficits – tell us very little.

Perhaps more importantly, their message is to look at free trade itself to understand the roots of the trade deficit of the US and trade surplus of China. The real reason is surprisingly simple: “It is the lower costs in China that drive its trade surplus”, Shaikh and Weber conclude. It’s not Chinese currency manipulation which, as Trump complained in 2015, “makes it impossible for our companies to compete”. It’s simply Chinese competitiveness. It’s an argument which may be harder to swallow for those convinced of the everlasting power and competitiveness of the US economy.

Politics, not economic science

However convincing their debunking of the economic evidence may be, Shaikh and Weber are well aware that in the political arena the economic evidence plays a secondary role. U.S. presidents like Trump repeat the accusation of currency manipulation because of politics, not economic science, they note.

It’s been a “general pattern” in US foreign policy for some time, Shaikh and Weber write, to accuse trading partners of currency manipulation when they are running a trade surplus with the US, typically followed by the “demand that they enter into bilateral negotiations on a wide array of market liberalization policies”. Booming economies like Korea, Taiwan, Hongkong and Singapore faced the same accusation of currency manipulation in the late eighties and nineties, Shaikh and Weber note. China has repeatedly been accused of currency manipulation by the US Treasury since the nineties, Weber adds by email, with increased intensity “since the rapid expansion of the US-China trade imbalance following China’s accession to the WTO in 2001”.

So the return of the currency manipulation argument today, at a time when the US and China are fighting over the terms of a new trade treaty, is not surprising. But it is alarming, Weber says, as the unfounded accusation “is another step towards escalating the trade war”.

This article was also published by Rethinking Economics.