The importance of Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) in the context of economic development has slowly come to grasp people’s attention. The World Bank defines IFFs as “money illegally earned, transferred, or used that crosses borders.” Since 2006, the Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a Washington, DC-based think tank, has done extensive research on IFFs. Their studies emphasize that the developing world lost $7.8 trillion in IFFs between 2004-2013—whereby $1.1 trillion was lost in 2013 alone. Studies have shown there is a strong correlation between IFFs and higher levels of poverty and economic inequality. The United Nations just passed its first resolution on combatting IFFs, as it is pertinent to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. This article explores further how IFFs occur, their role in keeping economies from developing—especially in the African continent, and some suggestions to tackle them.

Illicit financial flows are often mistaken as capital flight. This assumption is false because capital flight could be entirely licit. We can group the IFFs in three categories: commercial activities, which account for 65% of IFFs; criminal activities, estimated to be about 30%; and corruption, amounting to around 5%. Trade mis-invoicing is the most common way illicit funds leave developing nations, averaging 83.4%. Trade mis-invoicing means moving money illicitly across borders by misreporting the value of a commercial transaction on an invoice that is submitted to customs. It is carried out by under-invoicing exports and over-invoicing imports. Under-invoicing the value of exports means writing the price of a good as being less than the price actually paid, in order to show reduced profits and then pay less in taxes. Once the good is exported, it will be sold at full price and the excess money will be put in an offshore account. Over-invoicing the value of imports is when the price of a good is listed as being higher than the seller actually intends to charge the client. The excess money is deposited in the importer’s offshore bank account. There is the misconception that IFFs are largely due to corruption when in fact they account only for 5%, as mentioned above. With invoice manipulation of prices, there is no need for bribing anymore.

Another scheme used in IFFs is misreporting the quality or quantity of the traded products and services. According to a report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the African Union Commission, in 2012, Mozambican records showed a total export of 260,385 cubic meters of timber, while Chinese records alone show an import of 450,000 cubic meters of the same timber from Mozambique. Other strategies consist of creating fictitious transactions (which consists of making payments on goods or services that never materialize), transfer mispricing (which involves the manipulation of prices), and profit shifting (which is popular among corporations looking for favorable tax rates).

Role of IFFs in Keeping Economies from Developing

Illicit Financial Flows act as a barrier to economies from developing and achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Illicit financial outflows—facilitated by secrecy in the global financial system—are bleeding developing countries dry. UNCTAD emphasizes that developing countries will need $2.5 trillion every year until 2030 to achieve their goals on health, nutrition, education and the rest. But pledged capital inflows are only around $1.2 trillion. Preventing or even reducing IFFs can fill this funding gap. Seven out of the past 10 years, IFFs were greater than Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) given to poor nations.

The IMF estimates that developing nations lose $200 billion from tax revenues per year due to IFFs, while OECD countries lose $500 billion. Specifically, the United States (US) loses $100 billion annually. Tackling IFFs is in the interest of the US. Even though both developed and developing countries are victims of IFFs, developing countries suffer greater losses.

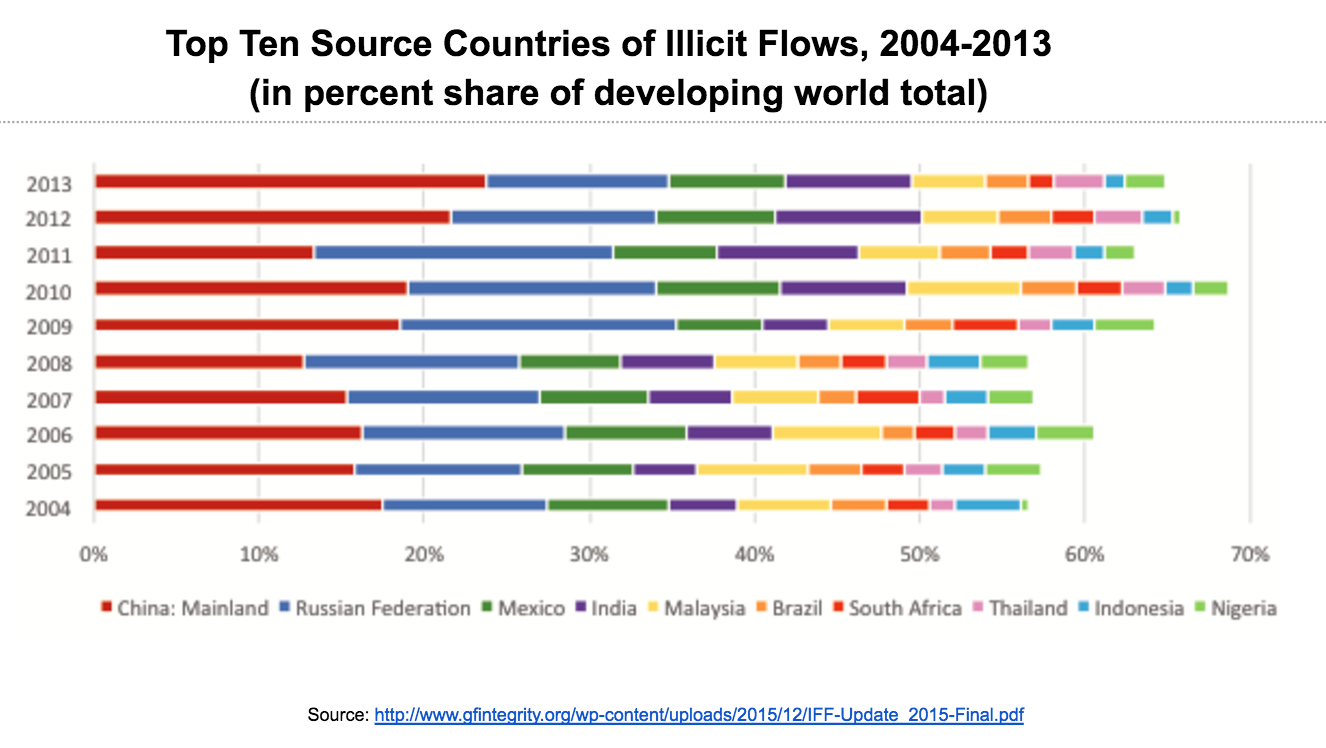

When it comes to most significant volume of IFFs, Asia is leading by 38.8% of the developing world over the ten years of this study. However, when IFFs are scaled as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), Sub-Saharan Africa tops the list averaging 6.1% of the region’s GDP.

At the Seventh Joint Annual Meetings of the ECA Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development and African Union Conference of Ministers of Economy and Finance in March 2014 in Abuja, Nigeria, a Ministerial Statement was issued, which states that:

“Africa loses $50 billion a year in illicit financial flows. These flows relate principally to commercial transactions, tax evasion, criminal activities (money laundering, and drug, arms and human trafficking), bribery, corruption and abuse of office. Countries that are rich in natural resources and countries with inadequate or non-existent institutional architecture are the most at risk of falling victim to illicit financial flows. These illicit flows have a negative impact on Africa’s development efforts: the most serious consequences are the loss of investment capital and revenue that could have been used to finance development programmes, the undermining of State institutions and a weakening of the rule of law.”

Former South African president Thabo Mbeki stated at a High-Level Panel on IFFs “Africa is a net creditor to the rest of the world.” The amount of IFFs out of Africa were between $854 billion and $1.8 trillion over the period 1970-2008, according to estimates by GFI. There is a campaign to end IFFs, “Stop the Bleeding”, led by Trust Africa Foundation. Mr. Mbeki stressed that Africa can no longer afford to have its resources depleted through IFFs. On the other hand, illicit financial transfers by African elites paint a different picture. It shows that African elites lack confidence in their own economies. Because they have the privilege to go abroad for education and healthcare, they are less likely to invest in their own countries.

Curbing IFFs

When searching the literature on IFFs, the focus seems to be on developing nations, which are the source. However, there is little focus on the destination countries like Switzerland, Ireland, United Kingdom, etc. A paper by GFI titled “The Absorption of Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: 2000-2006”, discusses that there are two types of destinations for money leaving the developing world. These are offshore financial centers and non-offshore developed country banks. The greatest challenge is getting the money back from the destination countries.

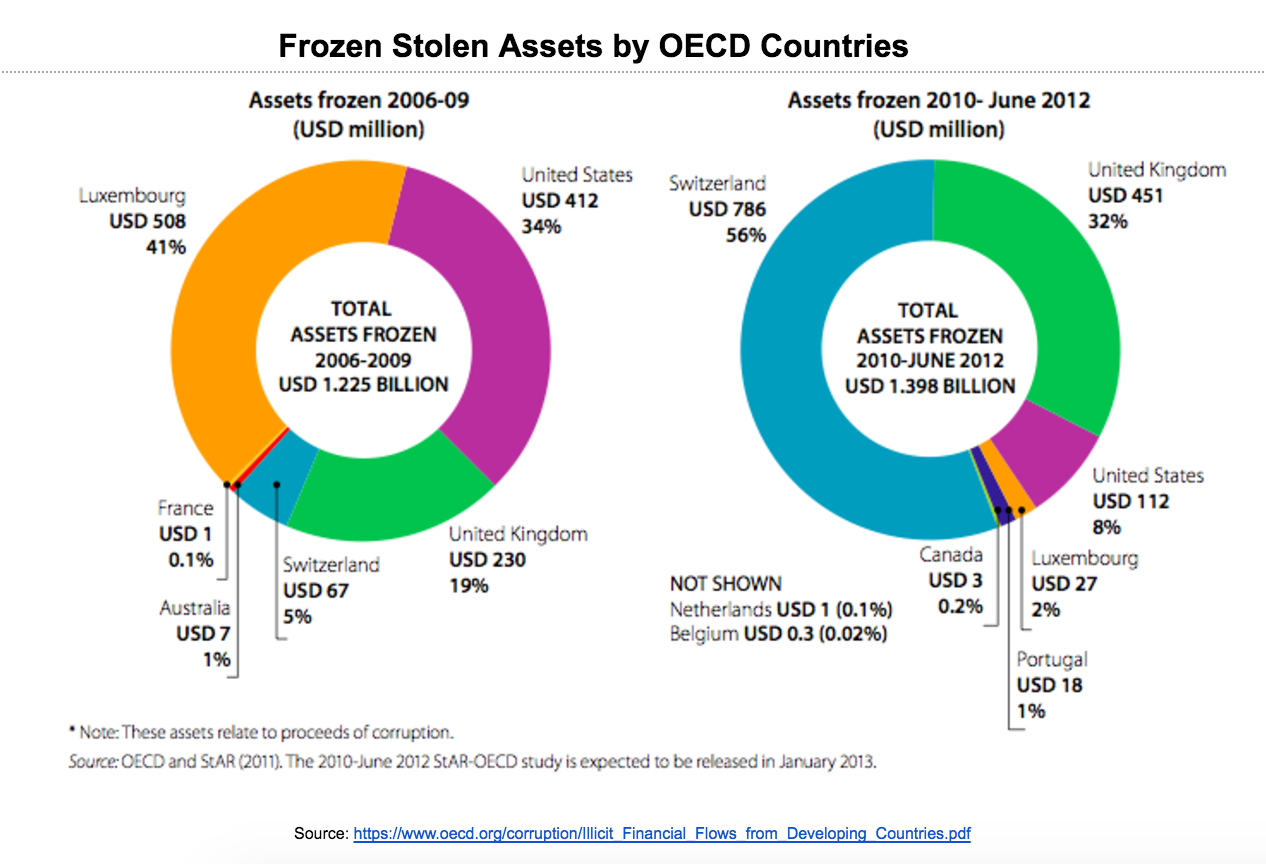

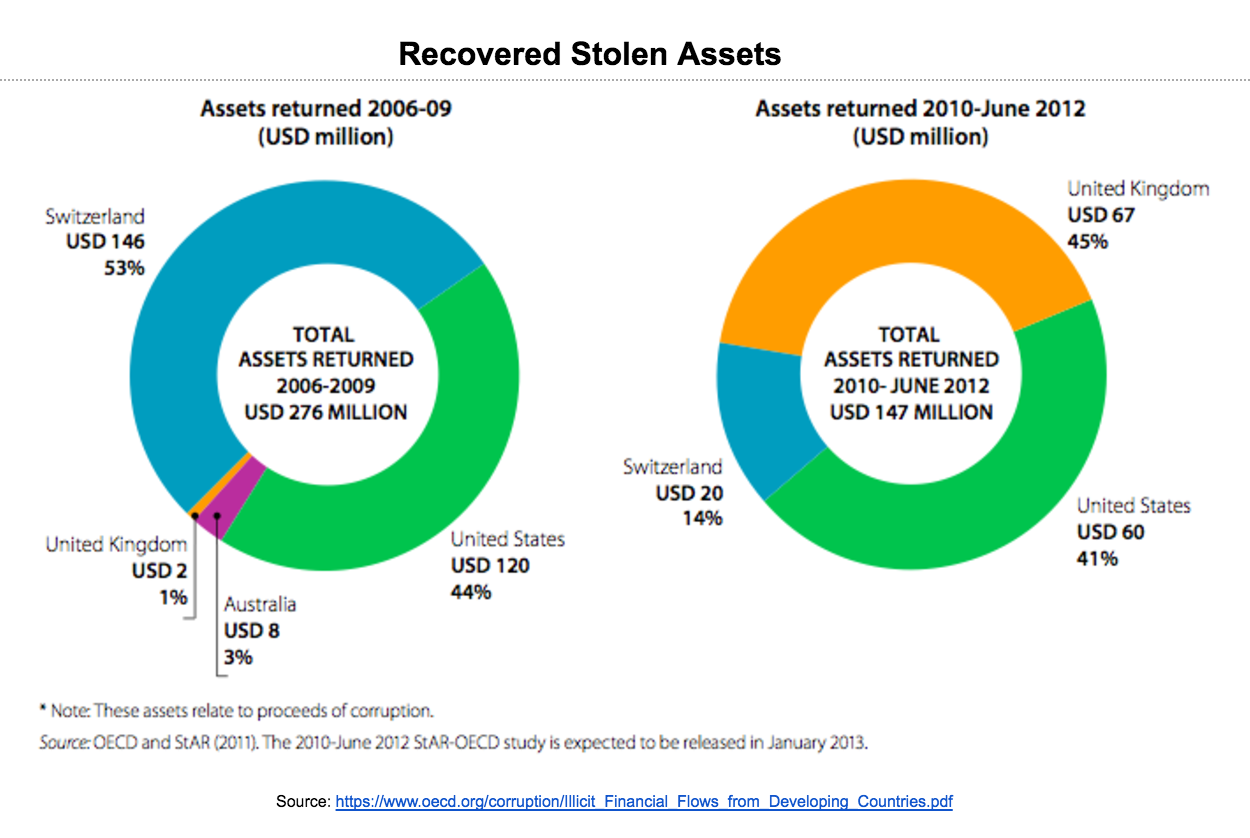

The OECD and the Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR) surveyed frozen assets held by OECD countries and how much of them were returned to the countries of origin . Between 2010 and June 2012, $1.4 billion of corruption-related assets were frozen and only $147 million was returned.

During the Arab Spring, banks and governments froze billions of dollars held by previous leaders along with their associates from Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya. However, following the Arab Spring, only few assets have been returned and the process of recovering stolen assets is very cumbersome. In order to recover stolen assets, there needs to be solid enough proof that these assets were in fact gained through corruption to begin with.

During the Arab Spring, banks and governments froze billions of dollars held by previous leaders along with their associates from Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya. However, following the Arab Spring, only few assets have been returned and the process of recovering stolen assets is very cumbersome. In order to recover stolen assets, there needs to be solid enough proof that these assets were in fact gained through corruption to begin with.

Illicit financial flows is an issue that plagues the developing world. Nations are denied tax revenues that could be geared towards providing necessities, employment, and economic growth. Nations should hold their financial institutions accountable if they participate in tax evasion activities. There is a need for the creation of financial supervision agencies focused on IFFs. Another suggestion would be the development of a global trade-pricing database so that customs officials are not tricked by false prices. Lastly, the Bank of International Settlement should publish data on international banking assets by country of origin and country of destination in order to better comprehend where IFFs are headed.

Written by Mariamawit F. Tadesse