By Juan Ianni. Why does mainstream economics recommend the application of Inflation Targeting (IT) regimes? Is it because of its sophistication? Are there other ways of addressing inflation? Perhaps a historical analysis of the roots of what is now the dominant stabilization regime can shed light on these questions.

Although the concept “financialization” is still up to debate, some economists like Chesnais (2001) argue that, since 1970, capitalism has mutated toward a “financialized” model of accumulation. According to Fine (2013), financialization is the derivation of the use of money as a credit other than the use of money as capital. Other authors believe that financialization is the determining structure of other (political, social, economic) structures. Long story short, this would mean that changes in social relationships produce new economic (and non-economic) structures, which replicate the mode of production (or “the dominant structure”). But what does that mean?

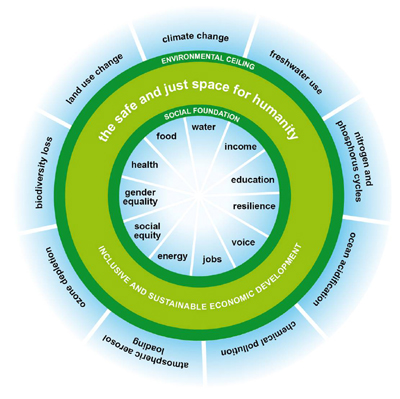

The French school of regulation can answer that question. According to the theory they developed, every accumulation pattern (for instance, “financialized” capitalism) needs a mode of regulation. The latter consist of a set of institutions (or policies), which enable social and economic reproduction by solving conflicts (inherent to every accumulation pattern) between agents of the society. Therefore, institutions will appear, disappear and relate in a non-random way, structuring a certain institutional configuration related to the accumulation pattern.

Boyer and Saillard are two of the most influential theorist of the French school of regulation. In one of their articles (Boyer and Saillard, 2005), they identify five core conflicts between agents in every accumulation pattern. Nevertheless, two are enough to understand the emergence of Inflation Targeting regimes: the “wage-labor nexus” and the “valorization of wealth”. While the first conflict refers to the dispute over the economic surplus between the worker and the capitalist, the latter refers to the prevailing mode of accumulation and valorization of wealth.

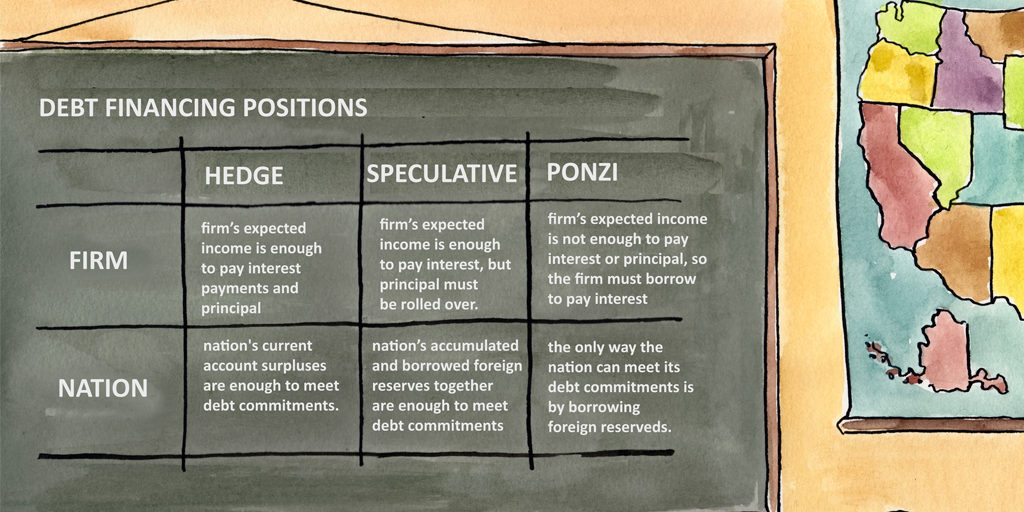

In their opinion, financialized capitalism is characterized for having the “valorization of wealth” as the central conflict to solve (or stabilize) within a particular set of institutions. In the contrary, the “wage-labor nexus” is the “adjustment” conflict. This means that accumulation will no longer be led by an equal distribution of the production surplus between workers and entrepreneurs. On the contrary, financialized capitalism will ensure a way for wealth to be valued related to credit (and not capital), no matter how damaging that could be to workers.

With the gestation of financialized capitalism (along with its respective institutional configuration process) and the centrality of the “valorisation of wealth” conflict, the New Macroeconomic Consensus was established as a theoretical paradigm. In order to legitimize and deepen this institutional configuration, it propiated the emergence and propagation of Inflation Targeting regimes as a conceptual apparatus regarding anti-inflationary policy-mix.

As these regimes consider inflation as an exclusive consequence of an excess in aggregate demand, contractive monetary policies are “always needed”. In the case of IT, they must constantly ensure a positive real interest rate, which fits perfectly with the need of a way to value wealth. What is more, it decreases inflation by incrementing unemployment, which shows how the “wage-labour nexus” is the adjustment conflict.

However, it is well known that inflation is a multi-faceted problem. Empirical research shows that in addition to an excess in aggregate demand, inflation can be the consequence of the distributive conflict, international prices, inflationary inertia, etc. The way IT address this phenomena (setting a high real interest rate, increasing unemployment, and letting the exchange rate float) shows how it is the perfect piece for the financialized capitalism puzzle. However, since the existence of very close interconnections between the international monetary systems and the national financial markets (what Chesnais call the “financial globalization”), IT’s effectiveness has lowered.

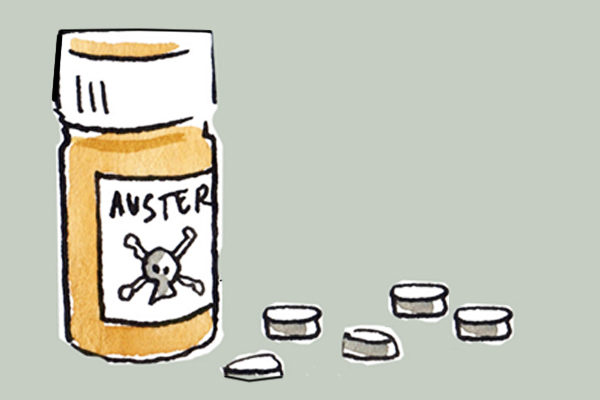

In addition, when the main cause of inflation is not related to an excess in aggregate demand, IT’s efficiency falls. Vera (2014) argues that using IT demands a strong reliance on the unemployment channel (that is to say, to stop inflation, unemployment needs to increase), which has adverse side effects on both employment and income distribution.

Given these drawbacks, some economic schools have developed other tools to tackle inflation, which may be both more efficient and effective. To that end, a different policy mix in which real exchange rate targeting is combined with income distribution targeting can be structured. In this case, the nominal exchange rate could be set to sustain a balanced external sector, whilst income policies could preserve a more equitable distribution of income. Consequently, a low level of inflation is sustained while the “disciplinary effect” of unemployment is avoided.

In conclusion, Inflation Targeting is not the mainstream policy instrument because of its results or theoretical coherence; after all, it has needless consequences regarding employment and income distribution. The main cause of IT’s popularity is that it assures the reproduction of an institutional configuration related to the “dominant structure”: financialized capitalism. Explaining this process, in addition to noting alternative stabilization regimes, should motivate the design and application of economic policies more consistent with increasing employment and a more equitable income distribution.

About the Author: Juan Ianni just completed a bachelor’s degree in Economics, and has a an interest in political economy and macroeconomics. He is currently studying alternative political schemes to tackle inflation, which is a big challenge for his home country, Argentina.