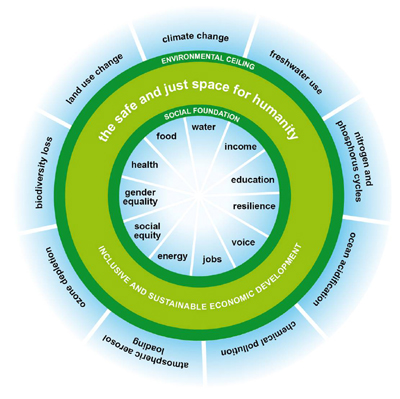

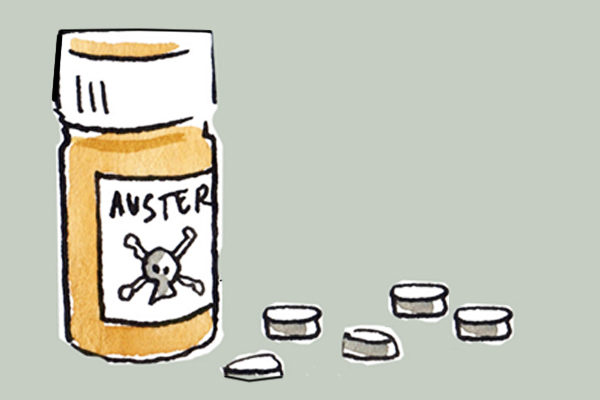

A series of protests have begun to rock Lebanon as of mid-March 2017. Protesters are taking to the streets to denounce the Lebanese government’s plan to introduce or increase 22 new taxes on citizens, most notably increasing the VAT tax from 10-11%, as well as various other taxes on food, drink, public notary services, and other categories that stand to impact daily purchases in the country. These measures will further reduce spending power of average Lebanese citizens during a time period when poverty has already risen by 66%(!) in the past 6 years, when around 30% of the population lives below the poverty line, when 9% of the Lebanese population lives on less than $1 per day, and when Syrian refugees continue to pour into Lebanon by the millions, further exacerbating Lebanese economic woes. Furthermore, Lebanon is the 3rd most unequal country on this planet in terms of wealth inequality, and this inequality implies that these new tax measures will primarily impact those who are already struggling to survive, let alone maintain a decent standard of living. In fact, these newly proposed taxes will be what economists call a “regressive tax,” since they will consume a bigger portion of the poor’s income compared to the rich.

The biggest complaint, rightfully so, of the protesters is that Lebanese politicians, with their entrenched system of confessionalism and nepotism, have stolen from public funds to aggrandize their own wealth, and have left the average Lebanese citizen struggling to survive off of the crumbs tossed to them. This rampant corruption, culture of excess, and paralysis of state oversight has contributed to a debt-to-GDP ratio of 140%, one of the highest in the world. Despite such mounting debt, the Lebanese government has little show for it in terms of providing services to the public.

For example, the Lebanese government cuts off electricity for several hours a day throughout the country— sometimes as much as 40-50% of the day, and claims that there are simply no public funds available to provide electricity for a full 24 hours. This is where the new tax proposal comes in; the government maintains that their hands are simply tied, and that these painful measures are needed to make a dent in paying off the public debt. However, when we examine the issue of public debt from the perspective of Modern Money Theory (MMT), we find that this idea is based on ignorance of how taxes and spending work at the public level.

MMT asserts that any sovereign government is capable of printing its own money into existence to pay for anything that it wishes to, from public healthcare to defense to infrastructure, or any other government-funded project. Because the government can create money out of nothing by simply printing it, or electronically transferring it to bank accounts, this by definition removes the necessity to collect taxes as a form of revenue to pay for things. The Lebanese government, for example, could have enough money to pay for electricity 24 hours a day if it simply created money to pay for it by electronically transferring the sum to the bank accounts to pay electricity companies. All of this can be done without ensuring that there is an equal amount of taxes flowing into the government, because the government does not use these taxes to pay for things. It pays for things by creating money out of nothing.

With this understanding, we can then reverse the causal relationship between taxes and public spending: taxes do not fund public spending. Rather, public spending creates the money by which citizens can conduct economic activity, including paying taxes. This is not an example of the classic “chicken vs. egg” conundrum. In this case, we can definitely say which side came first, for logical reasons. Citizens would simply not be able to pay taxes unless they had the money to pay for them in the first place, which in turn must be created by the government and released into the economy through public spending.

This implies that the government’s debt and deficit, as a matter of principle, does not matter to the public sector in the same way that a debt would matter to a household or firm. Government can always print more money in order to pay for things, including interest on debts. If a household tried to create its own play money and offer it to the credit card company at the end of the month, it would be rightfully ridiculed. However, because the government’s currency is universally recognized as bestowing the holder with value, it is accepted anywhere, and for “all debts, public and private.” In effect, it is the sovereignty of the state, and the credibility of their power to meet contractual financial obligations, that gives the money its value.

So, what then is the purpose of taxes, if they are not used to fund government spending? Primarily, taxes are a way of the government asserting sovereignty over its citizens. By denominating the taxes levied on citizens in the currency that they print, the government ensures that there will always be a widespread demand for its currency that people need to obtain to pay taxes. This ability to create money out of nothing and to generate widespread demand for it is a powerful component of state sovereignty, and, as other articles attest, the modern state as we know it would not even exist today without this power.

Taxes also serve another important economic function: they limit how much money a person can spend (purchasing power). When the government is worried about inflation (rising prices throughout society) brought about by rapid economic growth, for example, increasing taxes would be one way of decreasing spending in the entire economy, thus counteracting the threat of inflation. However, what does this mean for a country like Lebanon with a sizable percentage of its population living under the poverty line, and where the problem is too little spending and economic growth, not too much?

If Lebanese citizens have to pay increasingly higher taxes on daily necessities, their purchasing power will shrink. As their purchasing power and consumption declines, businesses will suffer. Investment and employment rates would likely decline, and poverty would increase. This increase in poverty would translate into citizens having even less money to contribute to taxes, since they would be consuming less and would have a smaller income. In such a situation, instead of these new tax measures decreasing the government debt, it is conceivable that they would actually do the exact opposite by increasing it, due to a decline in consumption and income, which are two of the biggest sources of taxes for the Lebanese government.

To conclude, it is time to admit the problems facing Lebanon are much more complex and fundamental than any new tax proposals would ever fix. Taxes do not create revenue for government spending, and in fact, new taxes in the country would even threaten to propel the already unacceptably high poverty line in the country even higher, as incomes and purchasing power are eroded. There is no reason to believe that the government debt even needs to be paid off in the first place, since government can never run out of money to pay for things, including debt servicing payments. Rather, the most fundamental problem in Lebanon is a political system characterized by diversionary religious sectarianism, and a culture of corruption and disdain for the masses that have allowed the Lebanese politicians to usurp public funds for personal gain, all while keeping a stranglehold on the people’s aspirations for freedom and dignity for decades.

Written by Stephanie Attar

Stephanie is part of the third group of students studying at the Levy Institute. Prior to coming to the Levy, she completed a masters degree in political science, with a concentration in political philosophy. Her research always incorporates Marxian dialectical materialism in order to analyze the interconnected nature between the state and the economy. She is also interested in the Arab world, global inequalities engendered by capitalism-imperialism, and radical solutions to advance the interests of humanity.