It’s disappointing to see debates between proponents of the Basic Income Guarantee (BIG) and the Job Guarantee (JG). These discussions detract from the fact that both of these ideal policies are distant from the policies we currently have in place. Supporters of either of these policies should be working together to get either one implemented, and we can debate adding the other later. Today, we need to move beyond our current disjointed welfare system to one that will help Americans, and either policy (or both!) seems like a step in the right direction.

If we look at the current system, the three largest welfare programs we have are Medicaid, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Before the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Medicaid was limited to certain low-income individuals, but the ACA expanded this program so that all adults with incomes below 138% of the federal poverty line are eligible. For FY 2015 Medicaid cost $532 billion to cover 73 million individuals. EITC provides additional income to low wage workers, and in 2014 paid out $67 billion to 27.5 million tax filers. Finally, SNAP guarantees an income to buy certain necessary items, and paid out $69 billion to 22 million households in 2015.

Then beyond those three largest programs, we have a smattering of additional programs that help the poor in this country. There’s a housing assistance program, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for the elderly, Pell Grants for college tuition, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families(TANF) program, the Child Nutrition Program, the Head Start preschool program, various Job Training programs (like AmeriCorps and Job Corps) under the Workforce Investment Act, Unemployment Insurance, the Child Tax Credit, Supplemental Nutrition for Women, Infants, and Children(WIC), and then theres others I’m sure I missed (oh yeah, the Obama phone!) along with various state and local programs. The amount of overlap, overhead, and bureaucracy involved with running all of these programs surely diminishes their effectiveness.

All of these programs provide support by doling out income or necessities, with or without a requirement that the recipient be working. BIG and JG would both be ways to consolidate all of these programs, and then the debate becomes how much does someone have to work in order to receive assistance. A lot of people who advocate for BIG think that our current system has a lot of pointless jobs, and BIG would be away to allow those people to pursue something more creative. Considering that most entrepreneurs have one thing in common — access to capital — that may not be too far off. Then there are JG proponents who probably agree with that point, but think we can use the policy to help organize jobs that need to be done (liking cleaning up our environment, or building our infrastructure). Most people who support BIG worry that a JG would create “make-work”, quoting Keynes famous “bury bank notes and dig them back up” line. To them, just giving people the bank notes makes more sense. On the other hand, JG proponents worry about losing the social utility of work. People want to contribute to society, and they see work that needs to be done. Both policies seem hard to pass in todays political climate.

I think proponents of both the BIG and JG are disappointed with a U6 unemployment rate of 9.5%, current companies lack of interest in maintaining our environment, and over 45 million Americans living in poverty. Call it whatever you want, let’s guarantee every American access to the necessities: healthy food, shelter, and healthcare. Clearly this is going to require some people to do some work, so let’s make sure that work gets done with our social structure as well. Calling it a BIG or a Basic Necessities Guarantee (BNG) or a JG doesn’t matter so much to me.

In fact, I’d probably start with calling it the EITC. Get rid of the minimum income phase in, and we instantly have a “BIG”, with all the infrastructure already in place. It would only go to unemployed or low income citizens, since the EITC phases out, which helps it be a progressive policy. So that it can cover the housing benefits and others, we could expand the credit a bit too. How do we pay for this? It’s simple. Scrap the other welfare programs (keep Medicaid, that one’s complicated). The overhead of having all of these programs is gross. How feasible is this plan? Honestly, no clue. I’ve never made a policy. I’ve barely met anyone who even makes policy. It seems like the closest option there is, however. I can see the complaints already though. These ungrateful welfare abusers will buy alcohol and drugs with their new found income! Somehow it’s not OK to drink and do drugs if you’re poor, but if you’re rich, go for it, right? If you get rid of SNAP, people won’t buy food for themselves! Well surprise, there’s already a way to trade SNAP benefits for cash — it’s called craigslist.

Then there’s the other major complaint this would cause — now there is no incentive to work. We have to keep abject poverty as a social option so that people keep working at McDonalds making the McObese, and keep stocking the Wal-Mart shelves so that Wal-Mart can pay starvation wages which allow people to be eligible for the EITC in the first place. I’m not really sure those are the jobs that need to be done. If our low wage workers were working on local farms producing fruits and vegetables, I’d probably agree… someone has to do those things (or make robots to do them!). Yet I haven’t seen any proof an income stops people from working. It’s all speculation. I bet people still do things. Here I am, incomeless, and I’m doing something. I’m writing. I’m volunteering. I’m applying to jobs that I want to do and think will have a positive benefit. Getting rejected, but still, I’m trying.

Let’s see what happens when everyone has some cash on hand. If we start starving and need the government to force us to produce food, we’ll do it then. Yet from the friends I’ve talked to, boredom is a very potent driver of change. I know my fellow millennials and I have dreams of growing our own food in our parents backyards, or the empty lot across the street, or the empty K-Mart, or the empty mall. If only they’d let us. If only we had a little income, a little land, and some water to give it a try. If only the police weren’t killing and hurting us. If only Nestle wasn’t pumping out water from government land for free and forcing us to spend money on it. A lot of us worked our asses off at school, and what did we get? The choice between huge corporations who we see as destroying the environment, or low incomes working retail living with our family and friends. Meh. My friends and I want something different. I choose believing there’s something better than choosing between two evils.

Remember when the public hated huge corporations for destroying small business, not each others’ identities? Do we remember The High Cost of Low Price? BIG and JG proponents, let’s not quibble. We’re on the same side. There’s work to be done. Get organized. Make it happen.

Originally published on Medium

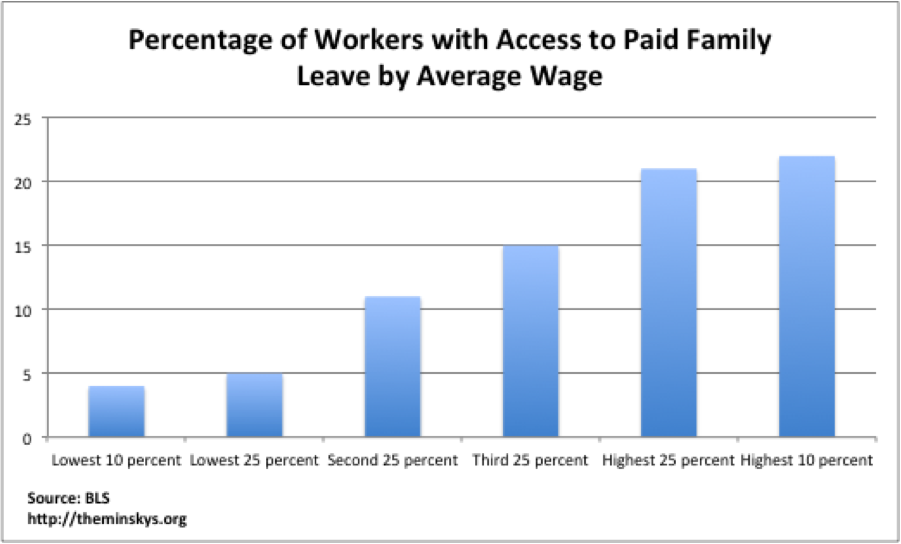

months for a company that hires at least 50 people. While this might be a start, it leaves about half of the workers uncovered. Even for those who are covered by the FMLA, they must afford giving up their paychecks for those 12 weeks. The act does little to help those who are left out or cannot afford to renounce their paychecks. This adds pressure on people at the lower end of the income distribution that might be pushed below the poverty line if forced to give up their incomes.

months for a company that hires at least 50 people. While this might be a start, it leaves about half of the workers uncovered. Even for those who are covered by the FMLA, they must afford giving up their paychecks for those 12 weeks. The act does little to help those who are left out or cannot afford to renounce their paychecks. This adds pressure on people at the lower end of the income distribution that might be pushed below the poverty line if forced to give up their incomes. introducing the policy had a positive or no noticeable effect on 89 percent of the businesses surveyed. However, these policies are very modest compared to the rest of the

introducing the policy had a positive or no noticeable effect on 89 percent of the businesses surveyed. However, these policies are very modest compared to the rest of the

disproportionately affects lower-income families is the cost of childcare. The Economic Policy Institute

disproportionately affects lower-income families is the cost of childcare. The Economic Policy Institute  With childcare costs

With childcare costs