In a meeting with Angela Merkel and Francois Hollande on August 22, the Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi proudly announced that Italy has the lowest public deficit of the last 10 years, and will continue with structural reforms to reduce it further. Monti has long aimed to “restore credibility” by cutting the public deficit, and now the Finance Minister Pier Carlo Padoan enjoys praise on his achievement of a deficit as small as 2.4% of GDP. The FED (Financial and Economic Document) goes so far as say this makes Italy “among the most virtuous countries in the Eurozone.”

A closer look at Italy’s economy, however, shows this “virtuosity” has no basis in reality. In 2015, 1.5 million households lived in absolute poverty. Another 4.5 million individuals saw stagnant incomes. The situation has not been this bad since 2005. In addition, the Migrantes foundation informs us that there has been a boom of italians who go abroad, 107,000 in 2015 (+6,2%). Especially youth from 18 to 34 years old (36,7%).

Source: [Ansa.it “Rapporto fondazione Migrantes”]

The percentage of serious material deprivation index is 11,5% for total households members. Official unemployment rate is at 11,9% whereas the real unemployment rate is well above the 20%. The inactivity rate is at 36,0 % and the fixed capital investment ratio is stuck well below the pre-crises (2007-08) levels.

Source: [“Rapporto annuale Istat, 2016”]

It is clear that Italy is stuck in a deep depression. And it’s not alone. Many other euro countries are suffering the same fate. Cutting public spending cannot help them recover. We turn to Keynes to see why it cannot, and consult the work of Minsky and Wynne Godley to see what can.

Keynes and Aggregate Demand

In The General Theory, J.M. Keynes explains the challenges blocking achieving and maintaining full employment in a market economy. He argues that the booms and busts associated with capitalism make this state of equilibrium very difficult to reach. When a bust occurs, and businesses expect their profits to fall, there’s no reason to expect a magical market-force to step in and fix employment while costs are being cut.

This applies to Italy, too. After years of austerity and a Global Financial Crises, aggregate demand levels have declined sharply most people feel uncertain about the future. Additional demand for labor is close to zero and the private sector is pessimistic. Investment and spending is not sufficient to employ the unemployed. Cutting down government expenditure is not going to to help. It will simply make it worse.

Minsky and Fiscal Policy

A follower of Keynes, Hyman Minsky explained how any analysis of a monetary capitalist economy must start from the analysis of balance sheets and its relative financial interrelations ‘measured’ in of cash flows. If balance sheets and especially the relative financial relations are not taken into account within an analysis of an essentially financial and monetary economy, that analysis fails to reflect the full reality.

Minsky’s alternative analysis shows that in case of crisis, a nation needs a “Big Government” (The Treasury Department) and a “Big Bank” (The Central Bank) to step up. These institutions must focus on serving as an “Employer of Last Resort” and a “Lender of Last Resort”, respectively. This way, they can prevent wages and asset prices from dropping further, and tame the market economy. In the Euro-zone, this has not been realized. The Treasury Department is constrained, leaving them unable to reach full employment. Meanwhile, citizens continue suffer under austerity.

Wynne Godley and the Government Budget

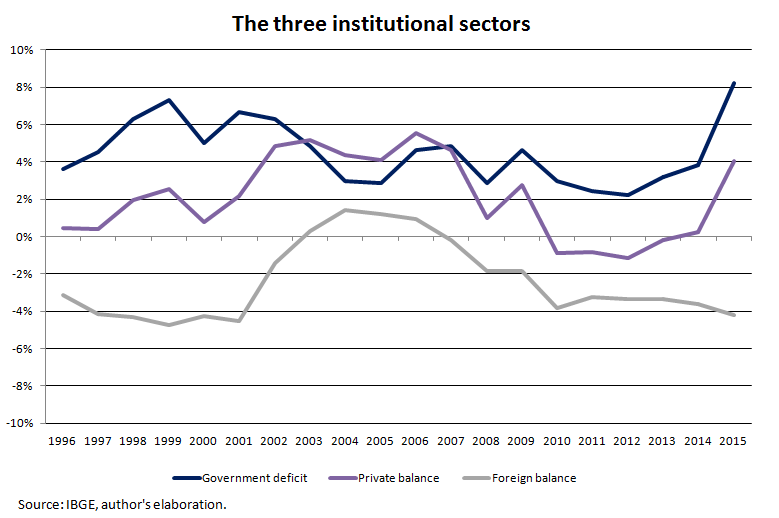

Wynne Godley’s sectoral balance approach sheds more light on this Minskyian alternative. He shows the economy consists of two sectors: The government sector, and the private sector (all households and businesses).** The private sector can accumulate net financial assets only if the other sector, government, runs a budget deficit. That is, only if the flows of the government spends more than it receives in taxes. It is impossible for both sectors to run a surplus at the same time.

And as a simple matter of macro-accounting, for aggregate output to be sold, total spending must equal the total income generated in the production process. So given households’ decisions to consume and given firms’ decisions to invest, there will be involuntarily idle labour for sale with no buyers at current wages, if the government deficit spending is too small to accommodate the net desire to save of the private sector.

What Renzi and Padoan are Really Saying

We can now see what Renzi and Padoan are really congratulating themselves for. Having done nothing to lift a struggling private sector out of the recession, they patting themselves on the back for worsening it’s social and economic situation. Renzi may claim he will go to Brussels to “sbattere i pugni sul tavolo”, but his executives continue to respect the Stability and Growth pact regime, and decrease the deficit further.

From Wynne Godley, we know that further decreasing the government deficit corresponds to further deterioration the private sector surplus. So when the officials say they “need to put public accounts in order,” they are actually saying they will put households and business accounts in dis-order. So when they say that Italy has the lowest budget deficit of the last 10 years, they are actually stating that the government is draining more financial assets from the private sector than it has in a decade.

When they call Italy virtuous for keeping a smallest deficit, they assign virtue to the nation that most effectively perpetuates poverty and social disarray. When Renzi says that his non elected executive “will continue […] the reduction of the deficit for our children and grandchildren”, he is instead telling us that his government is going to reduce the net desire to save of the current population, to keep involuntary unemployment and part-time working levels high and to firmly deteriorate the (net) financial and real wealth of the future generations.

Unless Italy changes its approach and adopts expansionary fiscal policy, it will not serve the well-being of the society and its economy. The main goal of full employment will never be attained and maintained. Work will lack moral and economic dignity, public sector goods will fall short in quantity and quality, and basic human rights will be violated. Not only will policy goals fail to be achieved, they will be even farther out of reach. One thing is certain: either Renzi and his ministers don’t know what they’re doing, or they are doing it in bad faith. I am afraid of it may be both.

* To be as precise as possible, Italian public budget deficit has been systematically reduced from 1991, that is the year when the Treaty of Maastricht was ratified which, among other things, established the respect of the parameter of the 3% to the public deficit and 60% to the (flawed) public debt/gdp ratio.

** I do not take into account the foreign sector balance sheet, because the substance of my brief argument won’t be undermined.

International conditions also played a major role in boosting the domestic economy. High international liquidity and the commodity-price super cycle guaranteed appreciation of the exchange rate, which beyond positively impacting domestic real wages, also helped to keep inflationary pressures under control by making foreign goods more accessible.

International conditions also played a major role in boosting the domestic economy. High international liquidity and the commodity-price super cycle guaranteed appreciation of the exchange rate, which beyond positively impacting domestic real wages, also helped to keep inflationary pressures under control by making foreign goods more accessible.