The global system has seen two major shocks in 2016: the Brexit vote and Trump. What these events have in common is their populist rhetoric that promised to bring back jobs. These elections have tapped into growing anxiety over job security, which has not been addressed by most governments and has given room for demagogues to tap into the anger of the people. They reflect a problem that transcends the boundaries of any single nation: the global economy has been in a slump for almost a decade. Governments need to create jobs, and public fiscal stimulus is the way to do so. To allow it, we must rethink that system.

To understand why we have to consider the international system in which nation states currently operate in. Its current characteristics present challenges for developed and developing economies alike. There are two important features to consider: first, the system creates a deflationary bias by requiring recessionary adjustments and hoarding of the international mean of payment (i.e. dollars). Second, it lacks mechanisms to offset the chronic surpluses and deficits between nations, thus breeding financial instability. In a nutshell, it leads to poor creation and distribution of demand that is managed through capital flows. Instead of propping up demand, the global economic system props up debt.

This post will be split into two parts. This first part will employ the theories of Hyman Minsky to explain the features of our current global economy. Next week, we will follow up to discuss an alternative system that would allow for a better distribution of demand among countries and would support emerging economies’ development by freeing them from the swings of international markets.

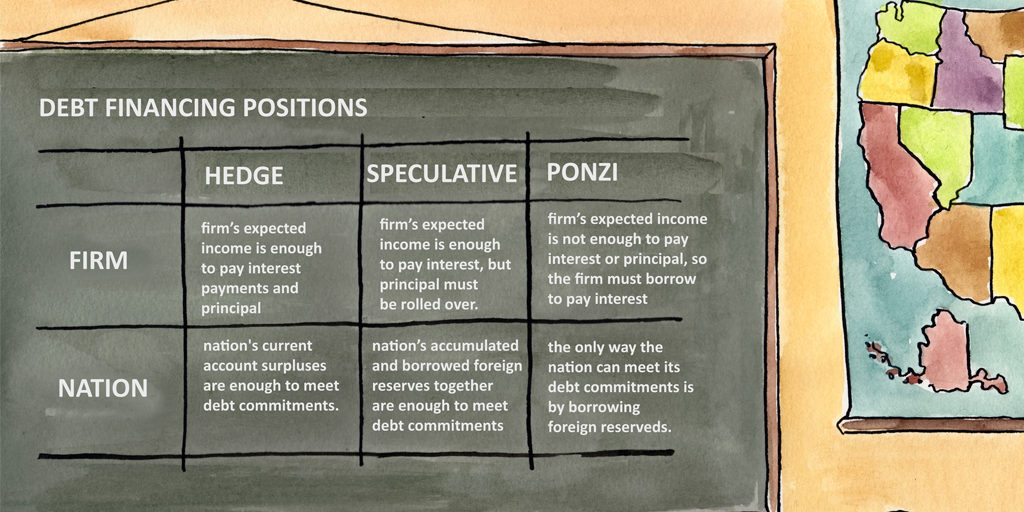

In his Financial Instability Hypothesis, Minsky addresses the ability of a company to honor its debt commitments. Companies can finance investment through previously retained earnings (internal funds) and/or by borrowing (external funds). If retained earnings prove to be insufficient, and the company comes more and more reliant on borrowed funds, the company’s balance sheet structure shifts from being stable to unstable. As presented in a previous post on this blog, Minsky described this process as moving from a stable “hedge” profile to a riskier “speculative” profile, and finally to a dangerous “Ponzi” profile.

Similarly, a country has three ways in which it can meet its debt commitments denominated in foreign currency: i) by obtaining foreign exchange through current account surpluses; ii) by using the stock of international reserves (obtained through previous current account surpluses); and iii) by obtaining access to foreign savings, i.e. borrowing. The first characterizes a hedge financial profile in which the cash inflows are sufficient to pay the foreign currency denominated liabilities. Any mismatch between inflows and outflows can be covered by reserves (its cushion of safety) or by borrowing; while the former can still characterize a hedge profile – as long as the cushion of safety is big enough to cover the shortfall for the necessary period of time – the latter is said to be speculative. In other words, the country borrows to cover a mismatch with the expectation that future revenues will be used to meet those debt obligations.

A situation in which further rounds of borrowing are necessary to meet those commitments is by definition a Ponzi scheme. It can only be sustained over time if it manages to keep fooling investors to continue to lend. Once a greater fool is not found and financial flows are reversed, the economy collapses in a Fisher-type debt deflation: as assets are liquidated to meet those financial obligations, their prices fall and the debt burden becomes increasingly heavier. The case of a country is different from a company, where outflows are often accurately expected, and it commonly leads to massive capital flight, currency devaluation, fall in public bond prices and increase in its premiums (i.e. interest rate payments). This last point illustrates the implications of accumulating foreign liabilities – reserves included – and implies the growth of negative net financial flows from borrowers to creditors through debt servicing. In general, from developing to developed countries.

The adjustment process punishes the borrower much harder than the lender. Greece presents a clear example. For the borrowing country, the standard imposed remedy is austerity: curtail of imports and public expenditure in order to forcefully meet those debts. Or, more often, to stir up enough confidence and access additional financial resources from private investors; in other words, continuing the Ponzi financing. Even in a case where interest payments on the borrowed funds are lower than the rate of capital inflow, the stock of debt would still expand, increasing financial fragility. A development strategy dependable on increasing usage of foreign savings is thus not feasible.

Of course, economic development is an extremely broad subject and we sure don’t want to commit the mistake of suggesting a “one-size-fits-it-all” policy a la neoliberal disciples. Nonetheless, a common issue for many developing economies is the lack of complexity and variety of its production structure – heavily dependent on primary goods – and the low price-elasticity of demand for its exports, which means that shifts in prices (exchange rate) do not do much to stimulate exports (increasing demand). As such, price adjustments might not always work as expected. This is one of the rationales behind the familiar “import substitution industrialization” strategy that tragically seems to have become the case for the UK and US.

These common characteristics affect the ability of emerging economies to face both up- and downswings of the international economy with countercyclical policies. While international liquidity is abundant in booming periods, it becomes extremely scarce during the slumps. Both capital floods and flights can be domestically disruptive for a developing economy, affecting its employment and output level, solvency, and – ultimately, its sovereign power. With scarce demand and international liquidity, the indebted economy falls into the debt-deflation spiral: it has to incur in a recession big enough to collapse imports at a faster rate than exports thus generating surpluses to clear off debt.

It should be clear that besides being completely inefficient – as opposed to the argument commonly used by “free-the-capital” defenders – the current economic system does little to stimulate demand. It is quite the contrary. Notwithstanding, after almost 10 years after the financial crisis, the world economy is still suffering the consequences of economic “freedom,” and the fighting tool has focused excessively on monetary rather than fiscal policy. Instead of cooperation, we are prone to have currency wars, protectionism, “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies and chronic debt accumulation.

These points of criticism are not novel, but they do deserve more of our attention. The same applies to their solutions, which are the focus of Part 2 of this article.

International conditions also played a major role in boosting the domestic economy. High international liquidity and the commodity-price super cycle guaranteed appreciation of the exchange rate, which beyond positively impacting domestic real wages, also helped to keep inflationary pressures under control by making foreign goods more accessible.

International conditions also played a major role in boosting the domestic economy. High international liquidity and the commodity-price super cycle guaranteed appreciation of the exchange rate, which beyond positively impacting domestic real wages, also helped to keep inflationary pressures under control by making foreign goods more accessible.

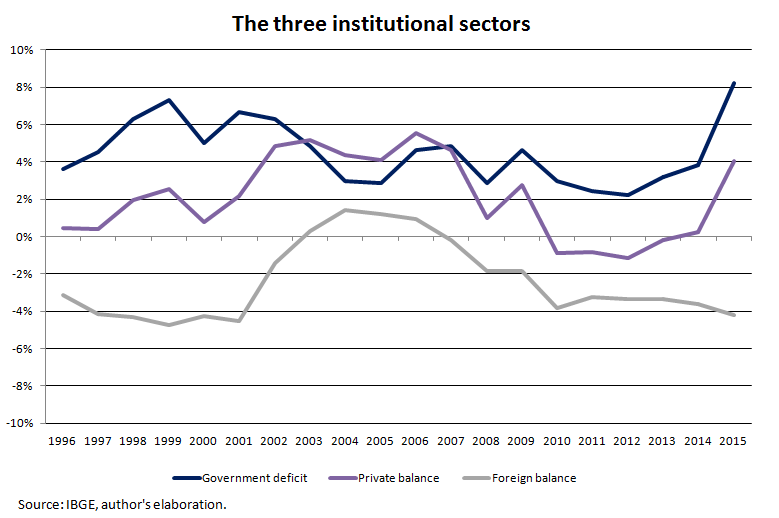

In order for households to get enough deposits so they can pay back their debts, the government should run deficits that end up in their hands. The reliance on the private sector has taken priority over the public good, and most of the deposits have landed in the hands of the top 1%. They were supposed to “

In order for households to get enough deposits so they can pay back their debts, the government should run deficits that end up in their hands. The reliance on the private sector has taken priority over the public good, and most of the deposits have landed in the hands of the top 1%. They were supposed to “