By Justin R. Harbour, ALM

In a recent Financial Times article, Martin Sandbu identifies three major economic failures of competitive capitalism in the West: growing inequality; the disproportionate effects of The Great Recession on young people; and the threat of displacement in labor markets brought by improving technology and the presumed ubiquity of artificial intelligence. Sandbu connects these failures to recent victories of populist “extremist” parties in the EU, UK, and US, and asserts that if liberalism and competitive capitalism are to remain a viable and persuasive platform for the next generations a bolder thinking from the Western political economy is now more necessary than ever.

This need to revamp Western capitalism has brought renewed attention to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a school of thought that offers an important and bold perspective on economics and policy solutions. A universal basic income (UBI), universal basic services (UBS), and a job guarantee by the State are most commonly cited as a bold fix to current problems. So, it is worth asking, what are the merits of these aforementioned proposals, through the lens of MMT?

The Failures of Competitive Capitalism

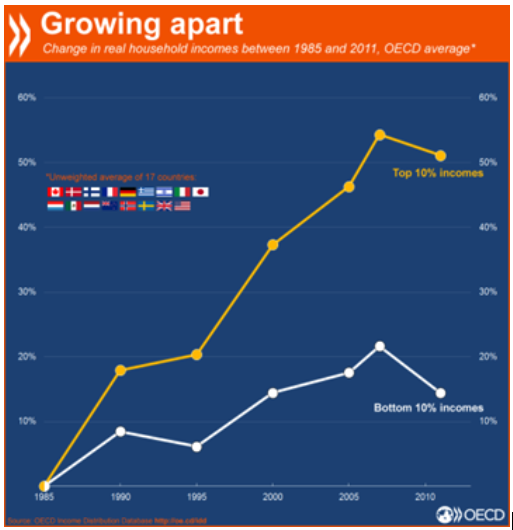

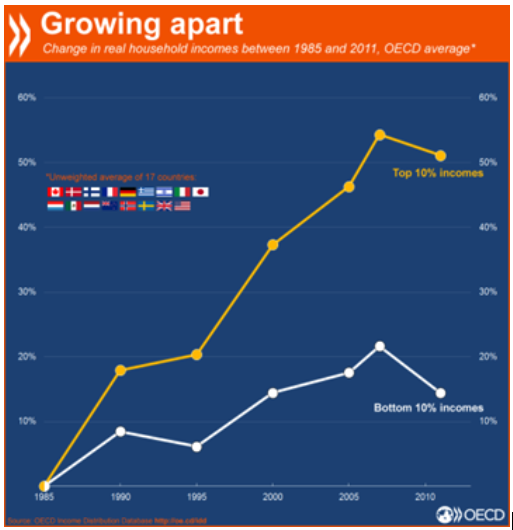

To answer this question, we first look at the failures of the competitive capitalism. Growing inequality is nearly universal. According to the Organization for Economic and Cooperative Development (OECD), the growth in inequality between the incomes of the top 10% of earners and the bottom 10% has not stopped since 1985:

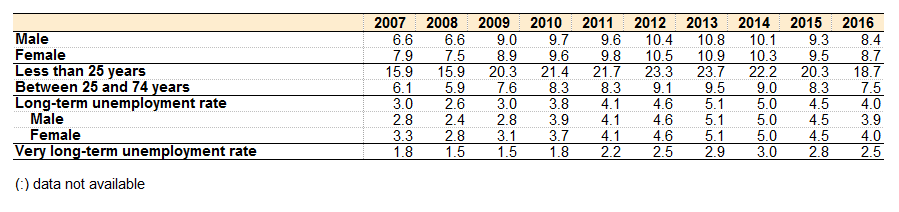

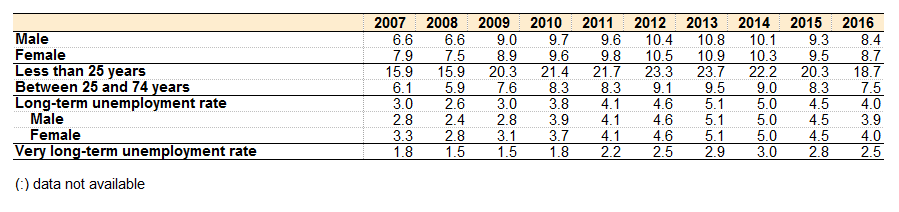

The Great Recession accelerated this trend and brought into stark relief the confounding need of the West to rescue and protect the Recession’s primary contributors (i.e., “too big to fail” banks). This approach made the resulting trends in unemployment all the harder to take, especially for the West’s younger workers. A 2012 report on the employment effects of The Great Recession by Stanford University found that those groups hit hardest were found those 25-54 years of age (i.e., the “prime working age” range, and hence a significant variable in overall economic growth). The report also found that minority groups found themselves bearing more of the burden than their racial-majority peers. A similar report from the Federal Reserve bank of St. Louis found that the recovery rates from unemployment after The Great Recession were lowest amongst younger prime-age workers and older workers. In Europe the young have fared even worse, according to a recent report from Eurostat:

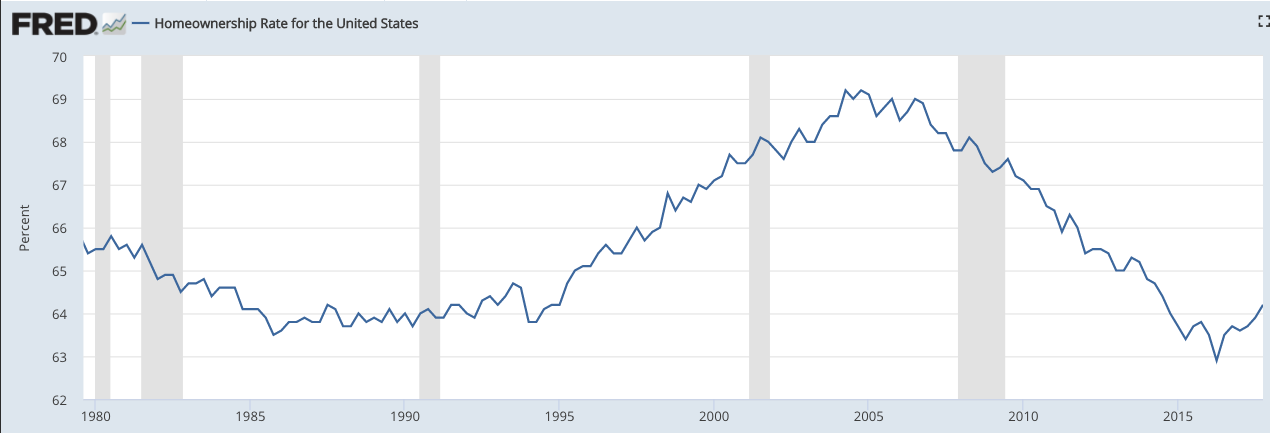

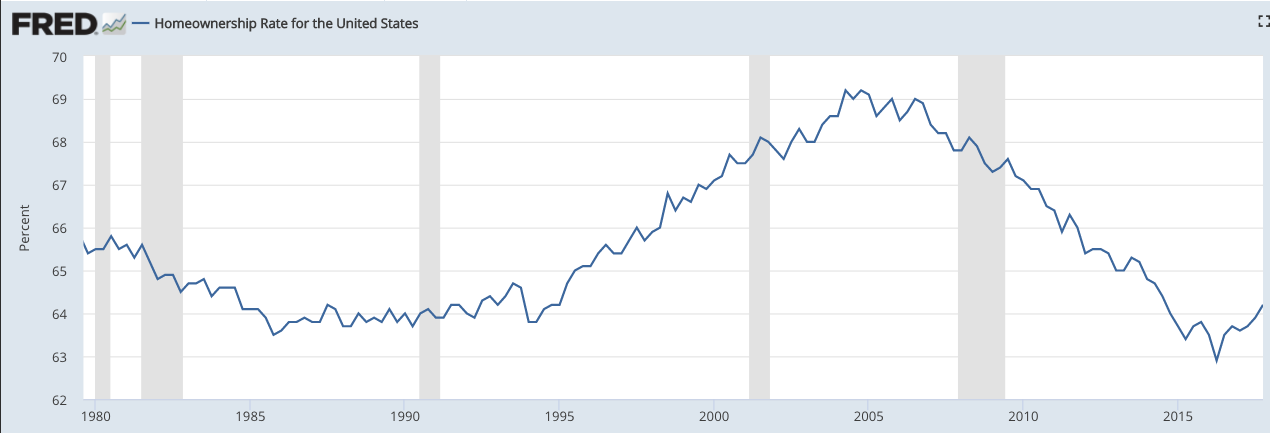

The story for wealth creation and asset acquisition for younger citizens homeownership is similarly alarming. Since World War II, homeownership has been considered to be the financial outcome indicative of a successful economy due to its positive value as a long-term asset. The decline in home ownership thus includes a worrying picture, ceteris paribus. As shown in the graph below, declining home ownership in the United States accelerated during the Recession, and remains at a rate not experienced since the economic boom of the nineties:

Though homeownership is less likely to be understood as a sign of economic success and health in Europe, research suggests a similar trend in declining home ownership in the aftermath of the Great Recession was also seen in the EU. Taken together, these trends make a generation’s economic skepticism of the ability of our current economy to deliver prosperity more of a logical first principle than not.

Three bold proposals to address this skepticism have become nearly commonplace in such reform-minded discourse: a UBI, a UBS, and a job guarantee. What does each propose, and which is best suited to address the issues identified above?

Three Bold Proposals

A UBI offers all citizens a basic level of income. UBI’s proponents commonly claim that this income is necessary for a variety of reasons. The fear of artificial intelligence taking over traditional labor tasks is commonly cited in defense of UBI. Some UBI proponents also argue that such an income would enhance human freedom by providing an option free from coercive and freedom-reducing labor arrangements. A UBI could also streamline social entitlement spending to be more efficient and less bureaucratic. A UBS does not offer income, but a variety of services deemed essential to maximize freedom and economic potential. Though the services offered differ between advocates, they often include improved and free public transportation, access to the internet, and job training, among others. A job guarantee is just as it sounds: anyone needing or wanting work but currently out of work would be offered a job by the local government to provide labor and/or services toward local projects that a community needs.

Each of these proposals includes explicit costs that must be heavily weighed. For example, the literal cost of providing a UBI substantial enough to achieve its purpose is very high. Some have suggested that its cost could range in the 30-40 trillion-dollar range in the United States. Cost-of-living variations also diminish the streamlining argument for a UBI since adjusting it for regional purchasing parity may make it even more complex bureaucratically than the current system. Explicit costs also represent an issue for UBS, though ostensibly less so than a UBI. Though the job guarantee does face some cost concerns, important work has recently demonstrated that the opportunity costs of such a program are well worth the explicit costs it may incur.

Though each proposal is bold in its promises and its trade-offs, the more important question here is which offers a better redress of the concerns raised by the Great Recession. It appears that the job guarantee is the better situated to address all those concerns on both explicit and implicit cost fronts. The job guarantee addresses the unemployment problem and wages problem directly. The job guarantee has the additional appeal of making it more likely that the newly employed will accumulate enough wealth to make home ownership an attractive option, and thus satisfy the third concern. Conversely, a UBI only deals with the wage issue directly and therefore the unemployment problem indirectly, while a UBS program does not address any of the problems directly. There are several other variables at play that strengthen the argument for job guarantee over the others. Most importantly, the job guarantee is the only one that signals the value of work – an implication necessary for future growth if an economy hopes to move beyond its current frontier. In doing so, it is more likely to find traction in our polarized political paradigm by avoiding the typical debates associated with strengthening social safety nets.

The Rise of Modern Monetary Theory

The economic school most strongly advocating for the affordability of a job guarantee program – Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) – has been experiencing a surge of public interest and acceptance as of late. This is not to say it is brand new or has not been trying to advocate for the policies its theory substantiates for a long time. But its appeal since the experience of the Great Recession is obvious once one digs into it. MMT is a theory of sovereign monetary policy that asserts that sovereign nations that issue debt in its own fiat currency cannot ever run out of money. Any restraint by a nation on their spending for any reason, including to stimulate demand or provide needed relief is, therefore, a purely political decision, and only restrained by the availability of real resources. MMT’s advocates thus model how under MMT’s reorientation of fiscal perspective, a nation’s fiscal and monetary policy options are much broader than under older and perhaps more dominant paradigms. The implication is that there are bolder and further reaching policy options always available to state to provide relief for distressed citizens during downturns if they can move beyond the unnecessary concerns for debt and deficits during such times.

The most notable of MMT’s more active contemporary economists include L. Randall Wray, Warren Mosler, and Stephanie Kelton. There are several websites dedicated to the defense of its theory by these authors and others: one by another of its theorists Bill Mitchell; and The Minskys, so named to honor one of the more prominent economists to set the foundations of MMT, Hyman Minsky. Of additional note would be Ms. Kelton’s work with the campaign of Bernie Sanders in 2016 and her recent inclusion into Bloomberg View’s stable of writers – an inclusion suggesting that MMT’s theories are gaining traction. There have also been recent news items such as a history of MMT in Vice News and a review of its contemporary appeal in The Nation. Finally, there has been the consistent work and advocacy of the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. MMT, in other words, appears here to stay.

Important work has been produced recently by MMT economists as well. In the United States, the Levy Institute recently published a report on the macroeconomic effects of canceling all student debt. The report finds that effects of such a policy would have a greater economic stimulus on employment and GDP than its costs can reasonably argue against. So too did the Levy Institute publish a report on the feasibility of the guaranteed job program discussed above. The job guarantee has helpfully garnered bipartisan support from the political right, left, and center.

Though popular within certain corners of the public sphere and gaining traction, it is not without its legitimate faults and challenges. Nonetheless, an undergraduate or higher level secondary student is unlikely to be exposed to MMT during their introductory training. I am not here suggesting that the more traditional curriculum is not appropriate for introductory students, nor universally ambivalent about the inclusion of emerging theories. But I am saying that for some teachers and some curriculums, finding ways to include such exciting emerging work with profound implications on their economic thinking and potentially their communities are harder the more they are not engaged with by “mainstream” outlets. What’s more, some of the more ubiquitous and far-reaching introductory curriculums (Advanced Placement in America, for example, or the International Baccalaureate program) don’t consider it at all.

At a time when some are rightfully calling for economists to better communicate economic concepts, ignoring newer and bolder conceptions of economic pillars that have popular momentum and real-world applicability behind them – such as MMT – leaves a fruitful learning opportunity to advance economic thinking and communicating skills for the youngest of economists at the door. Mr. Sandbu is right; the experience of the Great Recession by Gen Xers, Millennials, and those closely on their heels demands bold reform to reanimate the economy’s perceived legitimacy. A generation of economists and their work will be informed by their experience with the Great Recession. Let us all hope that MMT and its similar promising competitors are taken as seriously as the older theories so that we can rethink and rebuild economics in a way that makes economic thinking and understanding economic theory a universal pillar to our civic discourse.

About the author

Justin Harbour is currently an Instructor for Advanced Placement Economics at La Salle College High School in Philadelphia, PA. Having studied history, government, and political economy at UMASS, Amherst and Harvard University, he has previously published book reviews on teaching and education for the Teacher’s College Record and essays in CLIO: Newsletter of Politics and History, The World History Bulletin, and Political Animal. Justin lives in Philadelphia with his wife and two children. Follow him on twitter @jrharbour1