Traditional economics reveals the dynamics of exchange. But is that all there is? Late economist Kenneth Boulding recommends that we look further. Once we consider that some transactions only go one way, we can see the economy in a different light.

If you’re a high school student and you’re hungry for lunch, you may go out and buy yourself a sandwich. You give the deli guy five bucks, and he gives you a BLT. That’s exchange! But where did your five dollars come from? If you’re lucky, your parents gave it to you. Just like they gave you breakfast, your clothes, and a home to live in. And what did you give them? Probably your dirty laundry.

Modern-day, Western world parenting is an example of a one-way exchange. Parents provide for their children because the market doesn’t. And they do so without expecting much in return. Upon reaching adulthood, none of us receive an invoice detailing the costs we incurred. If we did, we’d probably be quite disturbed. In some cultures, children “pay back” by supporting their parents when they are older. But in the West, retirement plans, social security, and old-age homes have largely removed that expectation too.

Economist Kenneth Boulding advocated for such one-way exchanges, or “grants”, to be included in our study of the economy. Grants make up a big part of our distribution of resources, he argues, but economists have limited themselves to the study of exchange. To construct a more holistic framework in which both systems are fully represented, Boulding introduces “Grants Economics,” which adds to our understanding of the economy both at the micro-level (grants within the household) as well as at the macro-level (grants from the government*).

Boulding distinguishes grants by their motivating force. In the example of parental care, the motivating force is one of love. Parents provide for their children because they care about them. Charity, scholarships, and much of government transfers fall into the same category. But each economy also contains grants based on threat. If you’re about to buy your deli sandwich, and an armed robber comes in, you may hand over your money because you’re scared of getting hurt. That’s a grant as well.

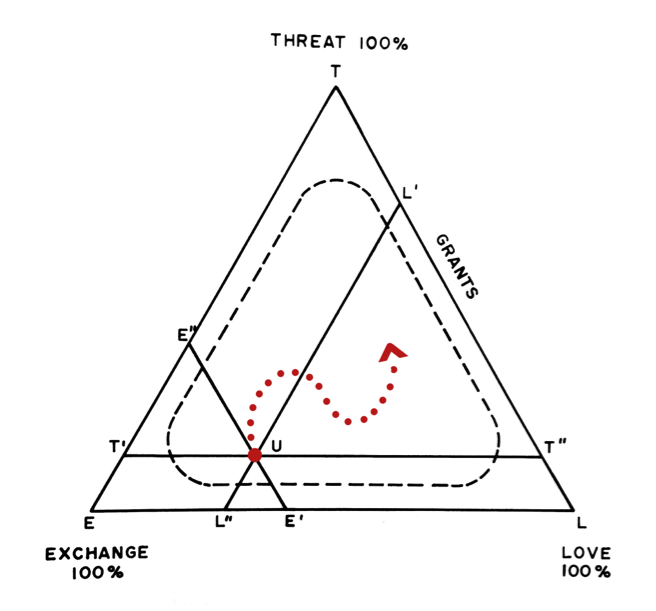

Every system, he explains, contains elements of exchange, love-based grants, and threat-based grants. But their respective shares in the total economy vary. To visualize this, Boulding presents a triangle, the corners of which represent a pure exchange-system, a pure love-based grant system, and a pure threat-based grant system. All the points inside the triangle represent different proportions in which the three systems can be combined. Where in the triangle we are, and where we are going, is the question.

At times, Boulding adds, the love-based grants economy may grow to compensate for failure in the exchange economy. If, for example, a hurricane strikes, we recognize the exchange system cannot support the situation, and make donations (grants) to fill the gap. But if we feel the efficiency of our grants is inadequate, the grants economy may shrink again. Only if perceive our grant to be able to be more useful in the hands of the grantee than in our own, do we want to provide it.

Since the 1970s, Boulding’s work has largely been forgotten. Perhaps because his definition of a grant, and the distinction between love and fear can be fuzzy at times, or because the scope of the theory is so vast. Nevertheless, the framework deserves credit for its potential to open our eyes to all the different ways in which resources are distributed. It can get us to think about the nature of our transactions.

Today, it may look like our current economy is increasingly based on exchange. Whereas we used to call a friend to help us assemble a new IKEA couch, many people may now use Handy to book an hour of paid-labor from someone they never met. Later that day, they may log in to TaskRabbit to hire someone for an errand. With the help of modern technology, Interactions that we would otherwise do without asking much in return are becoming two-way transfers.

At the same time, exchange continues to fail us, making large numbers of people rely on grants. In 2016, one in seven Americans received food stamps. That’s 43 million people for whom exchange is not bringing enough food on the table. On the other end of the income distribution, it may seem like things are different. But half of young adults (many with families of a high socio-economic status) rely on financial help from their parents. That’s a grant–typically with less of a stigma than food stamps–but a grant nonetheless.

These trends, and our potential path in the triangle raise various questions. How equal is our access to grants? Should we supply more grants (even a basic income?) or should we boost exchange (perhaps with a job guarantee?) Do we think we’re moving more towards a system based on love, in which care for one another dominates? Or are we finding it tough to get grants out of people unless we threaten them into providing them? Is there an ideal point in the triangle? Can we get there? Ponder on it. Boulding did so too, and being the only economist to sprinkle his books with poetry, he put his thoughts as follows:

Four things that give mankind a shove

Are threats, exchange, persuasion, love

But taken in the wrong proportions

These give us cultural abortions

For threats bring manifold abuses

In games where everybody loses

Exchange enriches every nation

But leads to dangerous alienation

Persuaders organize their brothers

But fool themselves as well as others

And love, with longer pull than hate

Is slow indeed to propagate

– Boulding, 1963

*Sometimes, of course, the lines between exchanges and grants are blurry. If we use taxes toward social security, and cash in at old age, that might be better described as a deferred exchange. If we, however, find ourselves on unemployment benefits, food stamps, rent support that we receive without having made an equal contribution, we can speak of a grant.