By Athullya Gopi | The US housing affordability crisis is driving more and more of the working poor to live out of cars and squatter homes- the solution seems to be creating more affordable homes in both urban and suburban areas where there is a high level of homelessness amongst the working poor but this means more carbon emissions and pollution in urban areas the long run. A green alternative needs to be found if both homelessness and pollution are to be solved simultaneously.

Homelessness is a growing global phenomenon. In the United States (US), its rampant increase is most evident in urbanized areas along the East and West coasts. Homelessness in the US does not only occur as a result of an individual’s perceived social and economic problems such as mental health and substance abuse issues or the stagnation of incomes, it is also the result of long-standing imperfections in the private US housing market that prevent everyone in the economy who demands housing as a dependable and primary source of shelter from accessing it. Such market imperfections limit the number of affordable housing units supplied by the private sector to urban low or very low income households – often making such individuals or households highly susceptible to homelessness as both incomes stagnate and rents or home values spike. An ideal long-run solution to reducing this type of homelessness is to employ federally mandated policies designed to increase the supply of available affordable housing units to those needing dependable shelter. The idea of increasing the number of physical dwelling spaces in already congested and polluted urban areas, however, implies an added burden to carbon emissions and energy utilization in cities at a time when careful consideration needs to be given to the latter. Is there a green solution to solving homelessness caused by the housing affordability crisis in the US?

The rapid growth of urbanization is most evident in the rising number of people living in cities – by 2030 it is estimated that at least 27% of the world population will be concentrated in cities with a population of more than 1,000,000. It is also clear that the rapid growth of urbanization is increasingly becoming a contributor to global climate change – although cities only account for less than 2% of the earth’s surface 71 to 76% of the world’s carbon emissions originate from urban areas. The impact of climate change is being increasingly felt in urban areas including its homeless. Since 2016 the number of homeless individuals in urban areas perishing from being unsheltered in extreme climate conditions has been increasing.

However, it is not just in urban areas that homelessness is growing. Poverty and homelessness have been increasing in suburban areas in the US over the last 15 years. With homelessness on the increase as a social ill not necessarily constrained by population density or geography more and more households/individuals who find themselves chronically unsheltered as a result will also be directly exposed to the increasingly devastating effects of climate change. A sustainable and joint solution needs to be found to address both problems, one that envisions more eco-friendly homes for those who need them as a source of shelter when they have no recourse to one.

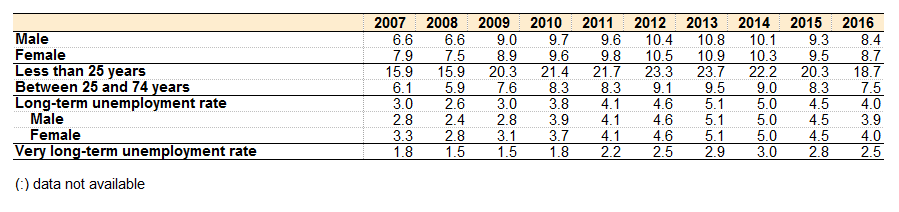

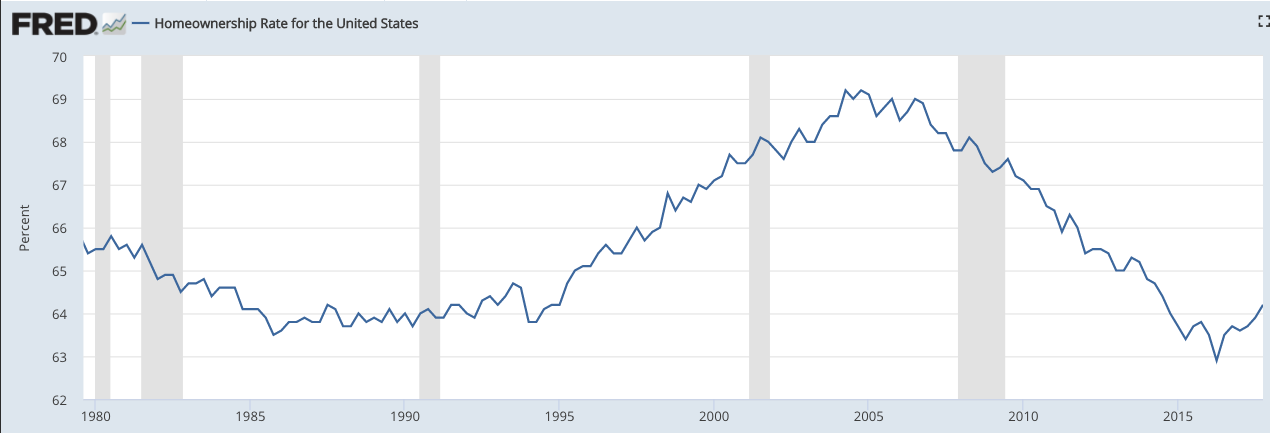

To start formulating such a joint solution we must begin with understanding the source of growth in homelessness over the last few decades. While foreclosures in the post-recession era have largely been responsible for people losing their owner-occupied homes, the source of homelessness relating to economic conditions extends beyond mere market forces that are freely operating. In the United States, the private housing market is an imperfect one, meaning that there are constraints imposed upon it that prevent demand and supply of housing from fully clearing. The imperfect housing market leads to renters being priced out of housing that is affordable when they are faced with either income shocks (like being made redundant when the economy goes down) or rental price shocks (when an upturn in the economy leads to a surge in property prices and therefore rents). This leads to a growing number of individuals/households that are at risk of becoming temporarily homeless. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) refers to such individuals as “transients”. Modern-day representations of homelessness are no longer restricted to the visibly homeless woman forced to live in her car while working as an adjunct professor and the army veteran who can only afford housing through a gofundme crowdfunding campaign. The housing crisis is one that is increasingly an affordability crisis.

The imperfect market leads to demand for housing persistently remaining relatively higher than the supply of available housing at any point in time. Often this mismatch between housing demand and supply is the result of the relative inelasticity (low sensitivity to price changes) of housing supply. Generally speaking when the price of a good or service increases, the supply of housing should respond over time by increasing too and vice versa. Housing supply, however, is relatively quite slow to respond to price signals due to a number of factors that do not directly impact the housing market. For example state regulations regarding land use vary across the United States and often favor the use of land in urban areas for commercial purposes rather than for housing, making it difficult to quickly increase housing supply in such areas in response to a sudden surge in housing real estate prices.

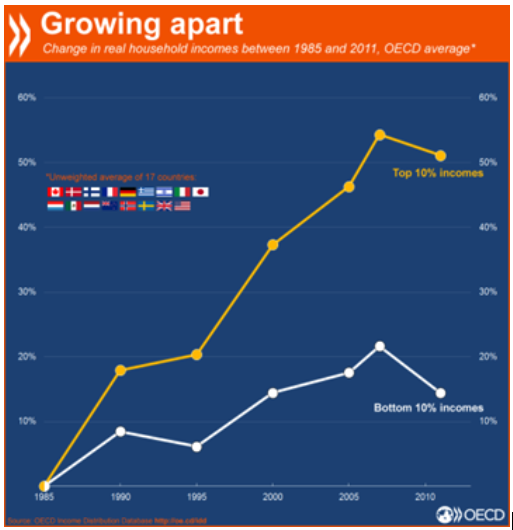

Additionally, the increasing use of housing real-estate as sources of investment leaves more and more units either vacant or used in a way that allows investors to gain higher than market returns – such as converting them to “AirBnB” units. This indicates that the market is biased towards those in the economy who demand housing real-estate as an investment good rather than as a basic form of shelter. This bias towards housing investors is clearly seen in urban areas by the rising levels of gentrification in cities – a way of making housing investments more attractive and therefore valuable to investors. Ultimately the existence of this bias means that richer entities/households that can afford to purchase or rent more than the one unit of housing they need for shelter gain access to the additional units they demand more readily than the relatively poorer households that need at least one unit for basic shelter. With a ‘sticky’ housing supply and a bias in how demand for housing is met, poorer households are ever more at risk of transient homelessness and not receiving at least the single unit of housing they require to meet their need for basic shelter.

Furthermore federal government safety nets for low income and very-low income households have been declining over the years instead of increasing: there have been no significant increases in federal housing voucher funding to make housing more affordable and more public housing units have been retired or demolished than built between 2000 and 2016 leading to an overall drop of around 200,000 units during this time. All of this implies a greater need for more physical housing units to be supplied outside of the imperfect private sector – to be made available ideally through federal government-led policy intervention that creates housing for the growing population of working poor that are most likely to be made transiently and then chronically homeless.

Increasing the supply of affordable housing to meet the real demand for housing as a source of shelter is only one half of a joint solution – the second half must resolve how to achieve this in a sustainable manner without adding to pollution levels. In this regard, special emphasis needs to be made on urban as opposed to rural areas mainly because the former are focal points of energy and durable goods consumption, both of which contribute significantly to the overall carbon footprint. For example, concentrated energy consumption in urban areas tends to create enough heat to change their surrounding microclimates, even causing them to differ in temperature on average by more than 1 degree Celsius than neighboring rural areas. Urban areas also generate undesirable runoff patterns in water – the way urban landscapes are constructed means that less water gets filtered back to replenish the local water table. At the same time urban areas, because of their warmer microclimates, generate more rainfall, meaning that run-off containing pollutants from industrial sites occurs more quickly and intensely than rural industrialized areas and significantly reducing water quality.

Innovative sustainable construction methods are becoming more popular. One example of a green construction standard is the Living Building Challenge, a green building certification program that outlines how sustainable built-up structures that are net water and energy positive (i.e. water is re-treated onsite and that more energy is generated onsite than consumed). This building standard was successfully used in a sustainable affordable housing project is present in Minneapolis. In 2015 two local nonprofit organizations, Aeon and Hope Community launched “the Rose”, a 90 unit mixed-income apartment complex with half the units assigned as affordable housing at a monthly rent of around $636 for a single bedroom apartment. What is remarkable is that the per square foot cost of constructing the Rose was less than a half that of a similar conventional high-end sustainable building. While it was 20% more expensive and more complicated to build than a comparable code-compliant building the Rose was intended to offer long-term cost-effectiveness by being up to 75% more energy efficient.

Affordable housing is largely not a favorable investment option for real-estate developers and so its sustainable development must be incentivized through policy change – one option would be through tax credits. However future policymakers must remain cautious about private investors using green building techniques in the name of climate change to deliberately ramp up property values.

Such an example appears in a case study of a multifamily residential property development supported by the City of Portland Oregon Department of Environmental Services. The latter is responsible for managing the city of Portland’s wastewater and stormwater infrastructure. In the Barrington Square Apartments project, the property owner retrofitted stormwater controls with greener technology that enabled the removal of more than 350,000 gallons of runoff with pollutants. While at first glance it appears that the Environmental Services Department that supported the project successfully promoted the implementation of green technology in the private sector to clean up of the environment, the project report indicates that the property owner was motivated to make these changes to increase the value of the property itself – an idea that is counter-intuitive to the expansion of sustainable affordable housing.

About the Author

Athullya is originally Indian, born and brought up in the United Arab Emirates. She joined the Levy Masters Program in 2016 after leading a successful career in credit insurance. The choice to swap her role as the head of commercial underwriting with that of a full-time student came after being inspired to see how Economics works in the real world. She now works at the Institute for New Economic Thinking in New York.