Keep track of all of Uber’s problems with The Big List of Uber’s Controversies.

In February 2017, Susan Fowler published a blog post detailing the sexual harassment and gender discrimination she experienced during her time as an engineer at Uber, the ride-hailing company. Although this was not the first time that Uber had been accused of creating a workplace where pervasive sexism and discrimination thrive, Fowler’s piece struck a chord. It built on a wave of criticism of the company from an earlier public relations disaster — Uber’s missteps following protests of President Trump’s racist executive order at John F. Kennedy Airport starting on January 28th and the resulting #DeleteUber campaign — and emboldened others to report sexual and other misconduct at the company (215 complaints about its corporate workplace have been filed).

While the criticisms levied at Uber are generally applicable to Silicon Valley as a whole, public ire was now focused on Uber, which was having a public relations crisis seemingly every week. The one-time $70 billion-valued private company (five times more valuable than the grocery store Whole Foods, which has 431 supermarkets, and was recently acquired by Amazon) was under immense pressure from even investors too. In response, it agreed to two investigations, both led by law firms. One investigated the workplace complaints that had been lodged against the company, leading to the firing of over 20 employees as well as disciplinary action against others. The second’s task was to investigate Uber’s corporate culture and develop recommendations to restructure the company to try to address the root causes of the problems. This team was led by former Obama administration Attorney General, and former Uber advisor, Eric Holder.

The report from Holder’s team, released a few days ago, came up with 13 pages of recommendations, all of which were adopted by Uber’s board of directors. In general, they seek to bring Uber in line with the practices of a company of its size. Some of these are common sense: developing internal controls and processes in a variety of ways, eliminating bias by performing blind reviews, reducing the unusually high amount of power of key executives, giving the board of directors more power, creating oversight and audit committees, using compensation as a carrot and stick, etc. Other recommendations include ensuring that people with children can participate in company events, which is laudable. Where the proposal fails is in its recommendations for changing values and emphasizing diversity, which include training for staff, developing programs to attract qualified diverse candidates, and reforming the list of the company’s core values (from something that a frat boy would write to, no doubt, corporate-speak clichés). It also included symbolic changes, like renaming Uber’s “War Room,” the “Peace Room”.

While revamping Uber’s structure and setting a bunch of (corporate) priorities might seem like a positive change at the company, it’s important to keep a few things in mind. One is that the problems that Uber is facing with regards to its culture and diversity are pervasive in Silicon Valley. Uber might be especially bad in these areas right now, but the typical solutions are unlikely to make much of a difference at the company because they haven’t made much of a difference at most tech companies. There are complicated reasons for these failures, and there should be little confidence that these tired and hollow strategies will work.

Another is that Uber is a private company, with control intentionally held closely among certain people, like CEO Travis Kalanick, who is most responsible for Uber’s reprehensible culture. As the CEO and founder, he ultimately controls much of what happens at the company, whether the Holder recommendations are adopted, and whether they are taken seriously. The most important result from the Holder investigation — Kalanick’s decision to take leave and take on a supposedly diminished role at the company — was undoubtedly due to pressure from the investigation but still entirely Kalanick’s own decision (and he’s still the CEO). Lastly, while the recommendations wisely agreed to use compensation as a way to incentivize and punish managers for transgressions, in practice, out-of-control pay of CEOs and executives, regardless of performance, is a systemic problem among not only tech companies, but companies in general. Kalanick’s poor performance as head of Uber should lead to a pay cut, but it likely won’t.

Thus, the Holder report might have some good ideas about how Uber could be run better, although it is unlikely that Uber will fundamentally change. (Indeed, at the board of directors meeting to discuss the results of the report, an Uber board member made a sexist remark.) But what this conversation about Uber misses are the more fundamental questions about Uber and its business. The narrative that has emerged about the company since the beginning of this year is that Uber’s problems start and stop at its management (specifically, Kalanick) and culture, when they don’t.

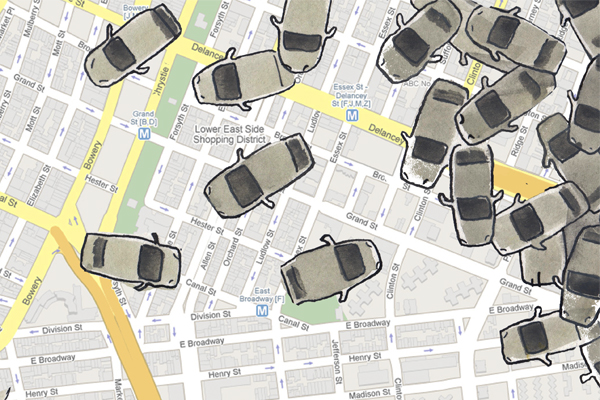

The Big List of Uber’s Controversies is a compendium of the problems and controversies that have plagued the company since its founding in 2009. Many of these are related to the problems the company is very publicly dealing with now; others are not. The goal of the list is to point out that Uber’s problems are pervasive and fundamental to the company’s operations, yet not necessarily unique to the company (although Uber might be an outlier with regard to how poorly it is managed and structured). To that end, the controversies are divided into six categories: Business Practices; Social Costs; Misuse of Data and Software; Corporate Culture; Passenger Issues; and Driver Issues.

While the 79 controversies and problems currently on the list touch on many different and unique issues, there are themes that give some insight into the inner workings of the company and its problems, and demonstrate that Uber’s problems run much deeper than its culture or even the company itself.

- Uber hemorrhages massive amounts of its investors’ money every year and does not have a viable business model, absent major changes in the industry or the creation of a monopoly;

- Uber’s success depends on attracting more investment and growing quickly, as well as anti-competitive practices: it has not created efficiencies or value that would justify its poor financial performance;

- Uber uses misleading research and fantastic technology forecasts to distract from the dismal failure of its core business, taxi service;

- Uber has large and sophisticated lobbying, public relations, and research departments, often involving former Obama administration officials, that deliberately misleads (and outright lies to) reporters, investors, regulators, and the public in order to justify and give cover to flagrant violations of the law, defend exploitative conditions, and paper over the problems with its business model;

- Uber erroneously claims that it is a technology — not a taxi — company, and that the business conducted on its platform is “sharing” in order to evade responsibility;

- Uber has inadequate internal controls for its data and software tools, leading to improper, and possibly illegal, access and use by employees, including to surveil critics and regulators;

- Uber’s growth-at-any-cost mentality and poor management has led to a culture that ignores problems and creates a toxic culture and workplace for its employees — significantly and negatively impacting its drivers and passengers as well;

- Uber’s past behavior suggests it has a complete disregard for the safety of its drivers and passengers until it is pressured to take action;

- Uber manipulates its drivers, entices them to enter into exploitative arrangements (including their misclassification as independent contractors), opposes their unionization, and exerts undue influence over their working conditions, consistently lowering their pay; and

- Uber’s operation has significant social costs with implications for public safety, public finance, access for those with disabilities, discrimination, investment in public infrastructure, and the regulated taxi industry as well as the taxi driving occupation.

Recent criticism of Uber is undoubtedly a good thing, but as this list demonstrates, its problems extend far beyond the individuals that run it or its corporate culture. With these problems, the fundamental question should not be whether Uber can reform its workplace culture, or whether Kalanick should stay on as CEO, or if he is overly important to the company. Rather it should be whether Uber, and companies like it, should be tolerated at all. In Uber’s case, it is unclear whether it is any better than regulated taxis broadly. Individuals might like Uber’s service — and that’s fine, and also to be expected, considering their rides are all subsidized by Uber’s investors — but policy should not cater what certain segments of the population want, especially if they don’t understand how the company operates.

Another important point is that Uber’s reckless behavior has been tolerated and excused because of its ascending position in the market. But as the clear industry leader today, that is part of the reason why it is now in the crosshairs, even though other ride-hailing companies suffer from some of the same problems as Uber. (Lyft eagerly capitalized on Uber’s misfortunes following the JFK protests, for example.) Importantly, they too have not developed ways to be profitable or more efficient than regulated, fleet-based taxis. Even Juno, the supposedly fair and ethical ride-hailing company that gave its drivers equity in its business, sold them out when it was acquired.

So, while some have suggested that the solution is simply to stop using Uber (and, ostensibly, to use competitors like Lyft or Gett), this is no solution at all. The solution is making sure that these companies are subject to the same regulations as traditional taxis, as well as that they comply with labor and other laws, all of which was unsurprisingly absent from the Holder report. This is the innovative idea that is also a solution to many of Silicon Valley’s problems, regardless of the industry.

Uber might not be able to survive if it started caring about the safety of its passengers, the exploitation of its drivers, or the social costs it shifts onto the rest of us (it’s in trouble already), but maybe it shouldn’t. As politicians plot with Silicon Valley to take over public infrastructure and to revamp the fundamental nature of work, maybe Silicon Valley shouldn’t either.

believed to be a distinct system with its own logic that requires experts to manage it.” Their work carefully explains why our current system is an econocracy and discusses possible ways to change that. Based on my own experiences so far, I can’t help but agree with them.

believed to be a distinct system with its own logic that requires experts to manage it.” Their work carefully explains why our current system is an econocracy and discusses possible ways to change that. Based on my own experiences so far, I can’t help but agree with them.