Progressives Trigger warning: Compassion required. When is the last time you heard Greens, Berniecrats or Indie voters not acknowledge the distinct and pressing need for election reform, campaign finance reform, voting reform? More to the point, when haven’t they mentioned unleashing 3rd parties from the fringe of irrelevancy and up onto the debate stage?

That is mostly what is talked about, simply because it is low hanging fruit.

It has long been known that our electoral system and methods of voting are corrupt, untrustworthy, and easily manipulated by less than savvy politicians, state actors, and hackers alike. The answers to many of these issues is the same answer that we would need to push for any progressive reforms to take place in America: namely, we need enlightened, fiery, peaceful, and committed activists to propel a movement and ensure that the people rise, face their oppressors, and unify to demand that their needs be met.

What is not as well-known, however, is how a movement, the government, and taxes work together to bring about massive changes in programs, new spending, and the always scary “National Debt” (should be “National Assets”, but I will speak to that later). In fact, this subject is so poorly understood by many well-meaning people on all sides of the aisle that these issues are the most important we face as a nation. Until we understand them and have the confidence and precision necessary to destroy the myths and legends we have substituted in the absence of truth and knowledge, it must remain front and center to the movement.

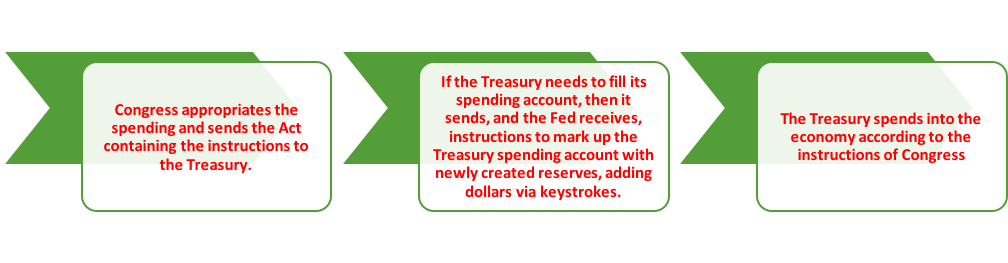

Progressives, like most Americans, are almost religiously attached to the terms “the taxpayer dollar,” and the idea that their “hard earned tax dollars” are being misappropriated. Often, the most difficult pill for people to swallow is the concept that our Federal Government is self-funding and creates the very money it “spends”. It isn’t spending your tax dollars at all. To demonstrate this, consider this simplified flow chart:

These truths bring on even more hand wringing, because to the average voter they raise the issue of where taxes, tax revenue, government borrowing, and the misleading idea of the “National Debt” (which is nothing more than the sum of every single not yet taxed federal high-powered dollar in existence) fit into the federal spending picture. The answer is that they really don’t.

A terrible deception has been perpetrated on the American people. We have been led to believe that the US borrows its own currency from foreign nations, that the money gathered from borrowing and collected from taxing funds federal spending. We have also been led to believe that gold is somehow the only real currency, that somehow our nation is broke because we don’t own much gold compared to the money we create, and that we are on the precipice of some massive collapse, etc. because of that shortage of gold.

The American people have been taught single entry accounting instead of Generally Accepted Accounting Practices, or GAAP-approved double entry accounting, where every single asset has a corresponding liability; which means that every single dollar has a corresponding legal commitment. Every single dollar by accounting identity is nothing more than a tax credit waiting to be extinguished. Sadly, many only see the government, the actual dollar creator, as having debt; that it has liabilities, not that we the people have assets; assets that we need more and more of as time goes on, to achieve any semblance of personal freedom and relative security from harm.

In other words, at the Federal level it is neither your tax dollars nor the dollars collected from sales of Treasury debt instruments that are spent. Every single dollar the Federal Government spends is new money.

Every dollar is keystroked into existence. Every single one of them. Which brings up the next question: “Where do our hard-earned tax dollars and borrowed dollars go if, in fact, they do not pay for spending on roads, schools, bombs and propaganda?” We already know the answer. They are destroyed by the Federal Reserve when they mark down the Treasury’s accounts.

In Professor Stephanie Kelton’s article in the LA Times “Congress can give every American a pony (if it breeds enough ponies)” (which you can find here ) She states quite plainly:

“Whoa, cowboy! Are you telling me that the government can just make money appear out of nowhere, like magic? Absolutely. Congress has special powers: It’s the patent-holder on the U.S. dollar. No one else is legally allowed to create it. This means that Congress can always afford the pony because it can always create the money to pay for it.”

That alone should raise eyebrows and cause you to reconsider a great many things you may have once thought. It will possibly cause you to fall back to old, neoclassical text book understandings as well, which she deftly anticipates and answers with:

“Now, that doesn’t mean the government can buy absolutely anything it wants in absolutely any quantity at absolutely any speed. (Say, a pony for each of the 320 million men, women and children in the United States, by tomorrow.) That’s because our economy has internal limits. If the government tries to buy too much of something, it will drive up prices as the economy struggles to keep up with the demand. Inflation can spiral out of control. There are plenty of ways for the government to get a handle on inflation, though. For example, it can take money out of the economy through taxation.”

And there it is. The limitation everyone is wondering about. Where is the spending limit?

When we run out of real resources. Not pieces of paper or keystrokes. Real resources.

To compound your bewilderment, would it stretch your credulity too much to say that the birth of a dollar is congressional spending and the death of a dollar is when it is received as a tax payment, or in return for a Treasury debt instrument, and deleted? Would that make your head explode? Let the explosions begin, because that is exactly what happens.

Money is a temporary thing. Even in the old days we heard so many wax poetically about how they took wheelbarrows of government — and bank – printed IOUs to the burn pile, and set the dollar funeral pyre ablaze.

In the same LA Times piece, Professor Kelton goes on to say:

“Since none of us learned any differently, most of us accept the idea that taxes and borrowing precede spending – TABS. And because the government has to “find the money” before it can spend in this sequence, everyone wants to know who’s picking up the tab.

There’s just one catch. The big secret in Washington is that the federal government abandoned TABS back when it dropped the gold standard. Here’s how things really work:

- Congress approves the spending and the money gets spent (S)

- Government collects some of that money in the form of taxes (T)

- If 1 > 2, Treasury allows the difference to be swapped for government bonds (B)

In other words, the government spends money and then collects some money back as people pay their taxes and buy bonds. Spending precedes taxing and borrowing – STAB. It takes votes and vocal interest groups, not tax revenue, to start the ball rolling.”

Let’s be clear, we are not talking about the Hobbit or Lord of the Rings. We are not talking about Gandalf the Grey or Bilbo Baggins. We are not referencing “my precious!”. It’s not gold, or some other commodity people like to hold, taste and smell. It is simply a tally. Yet somehow, we have convinced ourselves that there is a scarcity of dollars, when it is the resources that are scarce. We have created what Attorney Steven Larchuk calls a “Dollar Famine”.

To quote Warren Mosler in his must-read book “The 7 Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy” (you can download a free copy right here) he states:

“Next question: “So how does government spend when they never actually have anything to spend?”

Good question! Let’s now take a look at the process of how government spends.

Imagine you are expecting your $1,000 social security payment to hit your bank account which already has $500 in it, and you are watching your account on your computer screen. You are about to see how government spends without having anything to spend.

Presto! Suddenly your account statement that read $500 now reads $1,500. What did the government do to give you that money? It simply changed the number in your bank account from 500 to 1,500. It added a ‘1’ and a comma. That’s all.”

Keystrokes. Is it becoming clearer? Let’s go further for good measure. Mosler continues:

“It didn’t take a gold coin and hammer it into its computer. All it did was change a number in your bank account. It does this by making entries into its own spread sheet which is connected to the banking systems spreadsheets.

Government spending is all done by data entry on its own spread sheet we can call ‘The US dollar monetary system’.

There is no such thing as having to ‘get’ taxes or borrow to make a spreadsheet entry that we call ‘spending’. Computer data doesn’t come from anywhere. Everyone knows that!”

So why do we allow people to tell us otherwise? Maybe it is too abstract. And on cue, Mosler explains this phenomenon via a sports analogy for those who are not comfortable with the straight economic narrative:

“Where else do we see this happen? Your team kicks a field goal and on the scoreboard the score changes from, say, 7 point to 10 points. Does anyone wonder where the stadium got those three points? Of course not! Or you knock down 5 pins at the bowling alley and your score goes from 10 to 15. Do you worry about where the bowling alley got those points? Do you think all bowling alleys and football stadiums should have a ‘reserve of points’ in a ‘lock box’ to make sure you can get the points you have scored? Of course not! And if the bowling alley discovers you ‘foot faulted’ and takes your score back down by 5 points does the bowling alley now have more score to give out? Of course not!

We all know how ‘data entry’ works, but somehow this has gotten all turned around backwards by our politicians, media, and most all of the prominent mainstream economists.”

Ouch! Mosler pointed out the obvious, the propaganda machine has polluted our understanding. So how is this done in economic language? Let’s let Warren finish the thought:

“When the federal government spends the funds don’t ‘come from’ anywhere any more than the points ‘come from’ somewhere at the football stadium or the bowling alley.

Nor does collecting taxes (or borrowing) somehow increase the government’s ‘hoard of funds’ available for spending.

In fact, the people at the US Treasury who actually spend the money (by changing numbers on bank accounts up) don’t even have the phone numbers of the people at the IRS who collect taxes (they change the numbers on bank accounts down), or the other people at the US Treasury who do the ‘borrowing’ (issue the Treasury securities). If it mattered at all how much was taxed or borrowed to be able to spend, you’d think they’d at least know each other’s phone numbers! Clearly, it doesn’t matter for their purposes.”

So why do progressives allow the narrative that the nation has run out of points deter us from demanding we leverage our resources to gain points, to win the game of life, and have a robust New Deal: Green Energy, Infrastructure, free college, student debt eradication, healthcare as a right, a federal job guarantee for those who want work and expanded social security for those who do not want to or cannot work?

How has a movement so full of “revolutionaries” proved to be so “full of it” believing that we must take points away from the 99% to achieve that which the federal government creates readily, when people do something worth compensating? Why does the narrative that the nation is “broke” resonate with progressives? Why do they allow this narrative to sideline the entire movement?

I believe it is because progressives are beaten down. Many have forgotten what prosperity for all looks like or sounds like. Many are so financially broke and spiritually broken that the idea of hope seems like gas lighting. It feels like abuse. It crosses the realm of incredulity and forces people into that safe space of defeatism.

If they firmly reject hope, then they can at least predict failure, be correct and feel victorious in self-defeating apathy. If the system is rigged; if the politicians are all bought off; if the voting machines are hacked; if the deep state controls everything; then we think we are too weak to unite and stand up and demand economic justice, equality, a clean environment, a guaranteed job, healthcare and security and then we have a bad guy to blame.

Then we can sit at our computers, toss negative comments around social media, express our uninformed and uninspired defeatism about the system, and proclaim it is truth by ensuring it is a self-fulfilling prophecy about which we can be self-congratulatory in our 20/20 foresight as we perform the “progressive give-up strategy”. Or, if we want to achieve a Green New Deal, then in a radical departure from the norm we can own our power; we can embrace macroeconomic reality through the lens of a monetarily sovereign nation with a free floating, non-convertible fiat currency and truly achieve the progressive prosperity we all deserve.

The choice is ours. It is in our hands.

**For more of Steve’s work check out Real Progressives on Facebook or Twitter