On August 29th Dilma Rousseff, the democratically elected Brazilian ex-president, defended herself at the Senate against accusations of fiscal fraud, the so called “pedaladas fiscais.” Despite her defense, two days later, the president was formally impeached, putting an end to a process that has been carried on since May, when she first left office to face trial. The crime accusations were mainly accompanied by harsh criticisms of how the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT) fiscal irresponsibility led to the poor economic condition that the country finds itself. Among the economic meltdown and several scandals of corruption, her approval rate and the popularity of her party collapsed in recent years. After 13 years of the leftist PT administration, the presidency is now occupied by the then vice-president Michel Temer, member of the centrist Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro, PMDB), a party also involved in corruption scandals, and whose popularity is as bad as his predecessor.

Political matters “apart,” the Brazilian economic situation is indeed dire. GDP is expected to contract 3.18% in 2016, a second year of contraction, following the 3.85% in 2015. Unemployment increased more than four percentage points from the beginning of last year, reaching 11.3% in June 2016. Despite the poor economic performance, inflation is still above the 6.5% target roof, being expected to accumulate 7.4% this year. The inflationary pressure comes mainly as an effect of the rapid exchange rate nominal devaluation of almost 54% within the years of 2015 and 2016, reaching now R$ 3.29 per dollar. As an attempt to control inflation and attract foreign capital, the Brazilian Central Bank – going in the opposite direction of the major Central Banks – sharply rose the short-term interest rate (Selic), sustaining it at 14.25% (!!!) since mid-2015. This also had a feedback effect on the government’s total deficit. (*)

Two questions remain open: what are the real roots of the economic crisis and will the new administration be able to tackle it? To understand the roots of the bust, it might be easier to refer to the very causes of the boom that preceded it.

The boom and bust

From 2002 to 2008, the Brazilian economy performed really well, growing at an average of 4% per year. This was possible mainly by a combination of policies aimed to reduce poverty and income inequality along with the positive international scenario.

Increasing worker’s real wages and government cash transfers to poor households – channeled mainly through social security and the famous Bolsa Família – established a virtuous cycle of increasing private consumption. Another important factor was the promotion of policies towards labor-market formalization, which guaranteed not only access to social security but also the availability of poor households to private lines of credit. Note, however, that not only poor households benefited from “cash transfers”: the historically high short-term interest rate guaranteed that rich households too enjoyed the fruits of the boom. The government managed to attend then both extremes of the income distribution.

International conditions also played a major role in boosting the domestic economy. High international liquidity and the commodity-price super cycle guaranteed appreciation of the exchange rate, which beyond positively impacting domestic real wages, also helped to keep inflationary pressures under control by making foreign goods more accessible.

International conditions also played a major role in boosting the domestic economy. High international liquidity and the commodity-price super cycle guaranteed appreciation of the exchange rate, which beyond positively impacting domestic real wages, also helped to keep inflationary pressures under control by making foreign goods more accessible.

The Brazilian economy suffered its first hit with the 2008 financial crisis. Despite the GDP growth of 7.5% already in 2010, the fast economic recovery was mainly a result of aggressive counter-cyclical expansionary policies by the government, who acted through state-controlled enterprises (as the oil and energy companies, Petrobras and Eletrobras) and programs of investment in economic and social infrastructure. From 2011 on, GDP returned to low levels, making it necessary for the government to adopt a new set of policies that can be summarized in tax exemptions and subsidized credit expansion to private companies from public banks. As it happens, this attempt to increase private investment had the only effect of deteriorating the public fiscal situation.

The budget, the budget!!!

The change in orientation of government policies – from an expansion of public investment in 2008-10 to a provision of fiscal stimulus to private companies in 2012-14 – happened at the same time as the commodity boom ended. Already in 2011, commodity prices stagnated and, along with Brazilian terms of trade, started its downward path in 2014. The end of the commodity cycle had a harsh impact not only in economy’s aggregate demand but also on the fiscal budget.

Before we get to the fiscal issue though, please, don’t get me wrong. The cause of the Brazilian economic crisis is less a result of the end of the commodity boom in itself than by the productive structure that such cycle reinforced. Brazil’s external sector is highly dependent on the exports of primary goods, and this dependence only deepened in the past decade. In 2015, roughly 50% of Brazilian total exports were composed by primary products, a number that increased 4.5% per year since 2002, when it accounted for less than 30%. If we include natural resource-based manufactures on the calculus, it reaches nearly 70% of total exports! Furthermore, while labor productivity increased 5.3% per year from 2000 to 2013 in the agriculture sector, it decreased 0.6% per year in the manufacturing industry.

No wonder when commodity prices reverted trend the economy took a strong hit. Instead of setting the ground for the eventual bust, Brazil placed all its coins on booming commodities. Despite all the public investment programs and fiscal exonerations to the private sector, the PT administration did not manage to increase investment as share of GDP, which remained stagnant around the 18% level throughout 2002-2015 – with public investment accounting for less than 3% of GDP. Lack of investment in infrastructure and manufacturing industry perpetuated an anemic economy with low productivity and dependent on economic cycles.

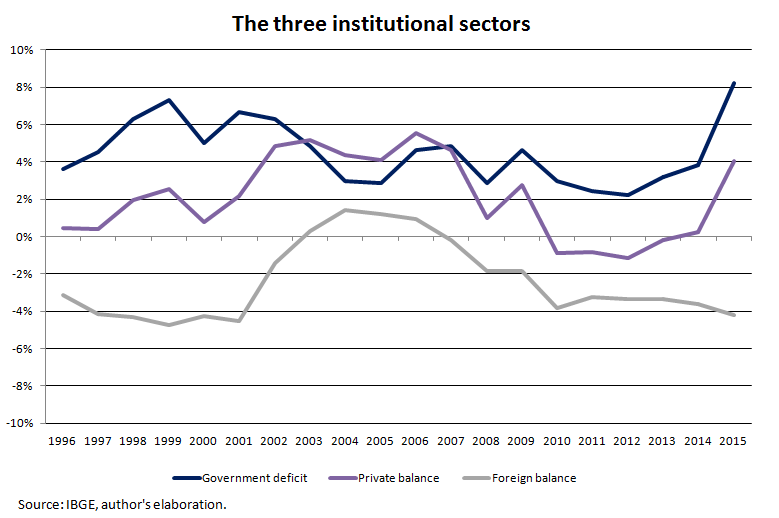

Public consumption and investment decreased even further after 2014 when the rapid deterioration of the fiscal budget turned the 3%-of-GDP government fiscal surpluses to almost 3%-of-GDP deficits. It is interesting to notice that the decreasing surpluses started in 2011, not accidentally when commodity prices stagnated. We can look at the three institutional balances for the Brazilian economy, representing the government, private, and foreign sectors, as follows below in order to see these trends more clearly.

We already know from previous posts on this blog (see here and here) that the government sector has a “crowding-in” effect on the private sector, meaning that government expenditure will, by an account identity, revert in private sector savings. Of course, in an open economy, this is only true as long as we assume the foreign sector to remain “stable”. Both the private and government sectors can only simultaneously run a surplus if the foreign sector generates a surplus that is big enough to account for both. (The intention of the figure presented is not to show that the balances sum to zero – which could be demonstrated by inverting the sign of the private sector and using a bar graph – but to show the movements of the financial assets and liabilities between the three sectors).

In the case of the Brazilian economy, the improvement of the foreign sector in 2001 allowed an increase in the private sector savings and a decrease in government total deficits. Once the financial crisis struck at the end of 2007, despite the counter-cyclical policies, the deterioration of the current account was mainly absorbed by a decrease in savings of the private sector, with government persisting to run primary surpluses and to sustain its total deficit level – even decreasing it until late 2012. On that year, we observe a sharp deleveraging of the private sector which, given the steady trend of the current account, was completely mirrored by the public sector.

Once again, the mistake – to name one – of the PT administration is that instead of increasing fiscal stimulus through direct government expenditure and investment in infrastructure it bet on providing credit and fiscal exonerations to the private sector as an attempt to increase private investment. In a scenario in which – to use Minsky’s terminology – the demand price of capital decreases at a faster rate than the supply price of capital, investment will not take place. In other words, despite the stimuli reducing the cost of new investment, expectations of profits were falling at a faster rate. In a situation of lack of aggregate demand, the government has to directly spend in order to create the necessary stimulus to the private sector through the generation of profits. Its avoidance led to the deterioration of the fiscal budget through the revenue side, surpassing now 10% of GDP, a result of the economic meltdown.

Instead of stimulating the economic activity by driving aggregate demand and adjusting the economy by sustaining the levels of output and employment, the government opted, mainly after 2014, for a “building confidence” strategy in which it compromises to reducing inflation, generating primary surpluses by increasing interest rates, and cutting government deficits, an adjustment that comes, in such case, through deepening the economic recession. All of it with the intention to attract market’s attention and foreign capital inflows. It, in fact, has a huge potential to generate financial fragility – but this is subject for another post.

And what now?

To address the second question posed at the beginning of this text, it is hard to believe that the new administration will be able to revert the dire scenario. It is still unsure if Temer will have the political leverage to pass important fiscal structural reforms in Congress, such as pension reform. Temer’s pledge to sharply reduce the government deficit can be summarized in the attempt to pass a law that will impose a limit to government expenditure indexed to the inflation level of the previous year. Besides reducing the ability of the government to invest, it also means cutting spending on areas such as education and public health, thus reducing the welfare state that was established in the previous decade, a major element in the virtuous cycle.

Whether or not promising to reduce inflation and the public deficit will be miraculously enough to stimulate agents confidence in the future, it will for sure hurt the economy and lead to a further decrease in demand price of investment in the short-run. In a situation of deleveraging private sector and slow global trade, it is unlikely that private investment will rise anytime soon. Until then, workers will be the ones to suffer from the increasing unemployment levels. The interest rate, beyond undermining any conceivable investment effort that could come from private agents, also carries a feedback effect to government budget and a distributive matter, as mentioned in the beginning of this text. When the pressure to cut government spending increases, “attend both extremes of the income distribution” becomes a hard job. We already know which side was chosen. Unfortunately, very often the adjustment burden comes from the weaker side.

(*) All the data presented in the text are extracted from the Brazilian Central Bank (BCB) and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).