“Bankers have an image problem.”

Marcy Stigum

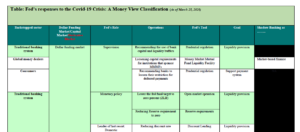

By Elham Saeidinezhad | Despite the extraordinary quick and far-reaching responses by the Fed and US Treasury, to save the economy following the crisis, the market sentiment is that “Money isn’t flowing yet.” Banks, considered as intermediaries between the government and troubled firms, have been told to use the liberated funds to boost financing for individuals and businesses in need. However, large banks are reluctant, and to a lesser extent unable, to make new loans even though regulators have relaxed capital rules imposed in the wake of the last crisis. This paradox highlights a reality that has already been emphasized by Mehrling and Stigum but erred in the economic orthodoxy.

To understand this reluctance by the banks, we must preface with a careful

look at banking. In the modern financial system, banks are “dealers” or “market

makers” in the money market rather than intermediaries between deficit and

surplus agents. In many markets such as the UK and US, these government support

programs are built based on the belief that banks are both willing and able to

switch to their traditional role of being financial intermediaries seamlessly.

This intermediation function enables banks to become instruments of state aid,

distributing free or cheap lending to businesses that need it, underpinned by

government guarantees. This piece (Part l) uses the Money View and a

historical lens to explain why banks are not inspired anymore to be financial

intermediaries. In Part ll, we are going to propose a possible resolution to

this perplexity. In a financial structure where banks are not willing to be

financial intermediaries, central banks might have to seriously entertain the

idea of using central bank digital currency (CBDC) during a crisis. Such tools

enable central banks to circumvent the banking system and inject liquidity

directly to those who need it the most.

Stigum once observed that bankers have, at times, an image problem. They are

seen as the culprits behind the high-interest rates that borrowers must pay and

as acting in ways that could put the financial system and the economy at risk, perhaps

by lending to risky borrowers, when interest rates are low. Both charges

reflect the constant evolution in banks’ business models that lead to a few

severe misconceptions over the years. The first delusion is about the

banks’ primary function. Despite the common belief, banks are not

intermediaries between surplus and deficit agents anymore. In this new system,

banks’ primary role is to act as dealers in money market securities, in

governments, in municipal securities, and various derivative products. Further,

several large banks have extensive operations for clearing

money market trades for nonbank dealers. A final important activity for money

center banks is foreign operations of two sorts: participating

in the broad international capital market known as the Euromarket and operating

within the confines of foreign capital markets (accepting deposits and making

loans denominated in local currencies).

Structural changes that have taken place on corporates’ capital structure

and the emergence of market-based finance have led to this reconstruction in

the banking system. To begin with, the corporate treasurers switched sources

of corporate financing for many corporates from a bank loan to money

market instruments such as commercial papers. In the late 1970s and early

1980s, when rates were high, and quality-yield spreads were consequently wide,

firms needing working capital began to use the sale of open market commercial

paper as a substitute for bank loans. Once firms that had previously borrowed

at banks short term were introduced to the paper market, they found that most

of the time, it paid them to borrow there. This was the case since money

obtained in the credit market was cheaper than bank loans except when the

short-term interest rate was being held by political pressure, or due to a

crisis, at an artificially low level.

The other significant change in market structure was the rise of “money

market mutual funds.” These funds provide more lucrative investment

opportunities for depositors, especially for institutional investors, compared

to what bank deposits tend to offer. This loss of large deposits led bank

holding companies to also borrow in the commercial paper market to fund bank

operations. The death of the deposits and the commercial loans made the

traditional lending business for the banks less attractive. The lower returns

caused the advent of the securitization market and the “pooling” of

assets, such as mortgages and other consumer loans. Banks gradually shifted

their business model from a traditional “original and hold” to an

“originate-to-distribute” in which banks and other lenders could

originate loans and quickly sell them into securitization pools. The goal was

to increase the return of making new loans, such as mortgages, to their clients

and became the originators of securitized assets.

The critical aspect of these developments is that they are mainly

off-balance sheet profit centers. In August 1970, the Fed ruled that funds

channeled to a member bank that was raised through the sale of commercial paper

by the bank’s holding company or any of its affiliates or subsidiaries were

subject to a reserve requirement. This ruling eliminated the sale of bank

holding company paper for such purposes. Today, bank holding companies, which

are active issuers of commercial paper, use the money obtained from the sale of

such paper to fund off-balance sheet, nonbank, activities. Off-balance sheet

operations do not require substantial funding from the bank when the contracts

are initiated, while traditional activities such as lending must be fully

funded. Further, most of the financing of traditional activities happens

through a stable base of money, such as bank capital and deposits. Yet,

borrowing is the primary source of funding off-balance sheet activities.

To be relevant in the new market-based credit system, and compensate for the

loss of their traditional business lines, the banks started to change their

main role from being financial intermediaries to becoming dealers in money

market instruments and originators of securitized assets. In doing so, instead

of making commercial loans, they provide liquidity backup facilities on

commercial paper issuance. Also, to enhance the profitability of making

consumer loans, such as mortgages, banks have turned to securitization

business and have became the originators of securitized loans.

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak, the Fed, along with US Treasury,

has provided numerous liquidity facilities to help illiquid small and medium

enterprises. These programs are designed to channel funds to every corner of

the economy through banks. For such a rescue package to become successful,

these banks have to resume their traditional financial intermediary role to

transfer funds from the government (the surplus agents) to SMEs (the deficit

agents) who need cash for payroll financing. Regulators, in return, allow banks

to enjoy lower capital requirements and looser risk-management standards. On

the surface, this sounds like a deal made in heaven.

In reality, however, even though banks have received regulatory leniency,

and extra funds, for their critical role as intermediaries in this rescue

package, they give the government the cold shoulder. Banks are very reluctant

to extend new credits and approve new loans. It is easy to portray banks as

villains. However, a more productive task would be to understand the underlying

reasons behind banks’ unwillingness. The problem is that despite what the Fed

and the Treasury seem to assume, banks are no longer in the business of

providing “direct” liquidity to financial and non-financial institutions. The

era of engaging in traditional banking operations, such as accepting deposits

and lending, has ended. Instead, they provide indirect finance through their

role as money market dealers and originators of securitized assets.

In this dealer-centric, wholesale, world, banks are nobody’s agents but

profits’. Being a dealer and earning a spread as a dealer is a much more

profitable business. More importantly, even though banks might not face

regulatory scrutiny if these loans end up being nonperforming, making such

loans will take their balance sheet space, which is already a scarce commodity

for these banks. Such factors imply that in this brave new world, the

opportunity cost of being the agent of good is high. Banks would have to give

up on some of their lucrative dealing businesses as such operation requires

balance sheet space. This is the reason why financial atheists have already

started to warn that banks should not be shamed into a do-gooder

lending binge.

Large banks rejected the notion that they should use their freed-up equity

capital as a basis for higher leverage, borrowing $5tn of funds to spray at the

economy and keep the flames of coronavirus at bay. Stigum once said that

bankers have an image problem. Having an image problem does not seem to be one

of the banks’ issues anymore. The COVID-19 crisis made it very clear that banks

are very comfortable with their lucrative roles as dealers in the money market

and originators of assets in the capital market and have no intention to be

do-gooders as financial intermediaries. These developments could suggest that

it is time to cut out banks as middlemen. To this end, central bank digital

currency (CBDC) could be a potential solution as it allows central banks to

bypass banks to inject liquidity into the system during a period of heightened

financial distress such as the COVID-19 crisis.

Elham Saeidinezhad is lecturer in Economics at UCLA. Before joining the Economics Department at UCLA, she was a research economist in International Finance and Macroeconomics research group at Milken Institute, Santa Monica, where she investigated the post-crisis structural changes in the capital market as a result of macroprudential regulations. Before that, she was a postdoctoral fellow at INET, working closely with Prof. Perry Mehrling and studying his “Money View”. Elham obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Sheffield, UK, in empirical Macroeconomics in 2013. You may contact Elham via the Young Scholars Directory