This Piece is part of the Stable Funding Series, by Elham Saeidinezhad

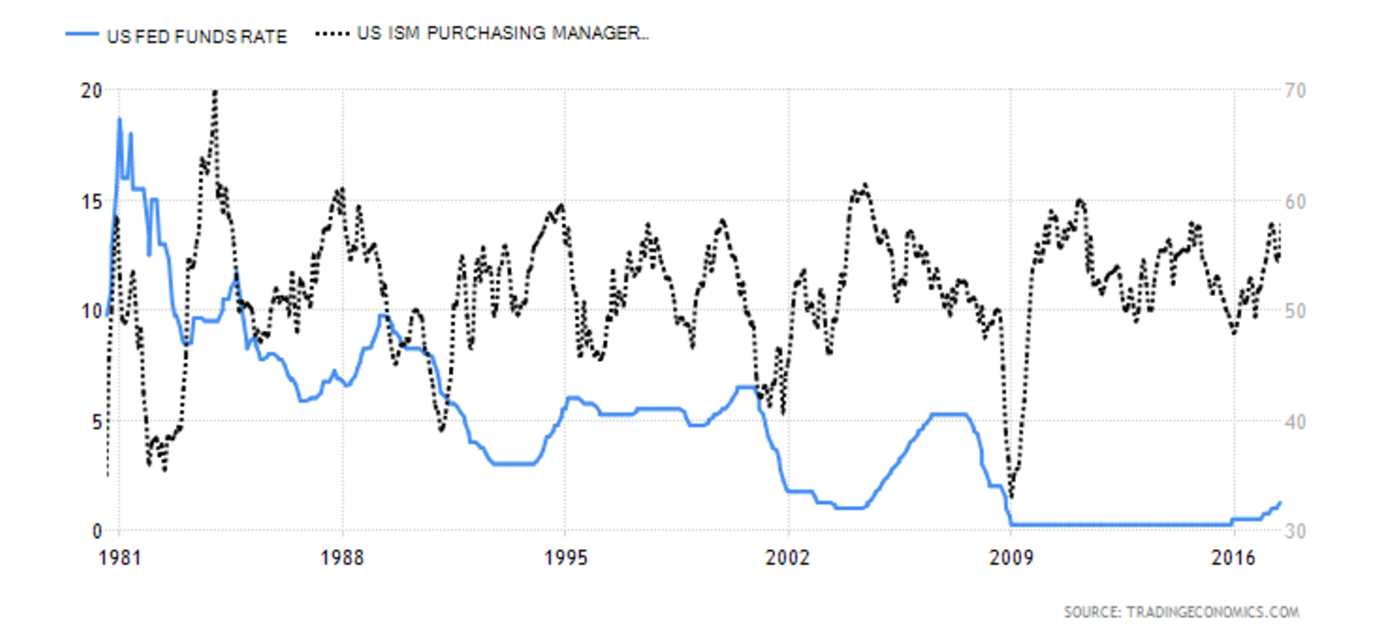

Mary Stigum once said, “Don’t fight the Fed!” There is perhaps no better advice that someone can give to an investor than to heed these words.

After the COVID-19 crisis, most aspects of the dollar funding market have shown some bizarre developments. In particular, the LIBOR-OIS spread, which used to be the primary measure of the cost of dollar funding globally, is losing its relevance. This spread has been sidelined by the strong bond between the rivals, namely CP/CD ratio and the FX swap basis. The problem is that such a switch, if proved to be premature, could create uncertainty, rather than stability, in the financial market. The COVID-19 crisis has already mystified the relationship between these two key dollar funding rates – CP/CD and FX swap basis- in at least two ways. First, even though they should logically track each other tightly according to the arbitrage conditions, they diverged markedly during the pandemic episode. Second, an unusual anomaly had emerged in the FX swap markets, when the market signaled a US dollar premium and discount simultaneously. For the scholars of Money View, these so-called anomalies are a legitimate child of the modern international monetary system where agents are disciplined, or rewarded, based on their position in the hierarchy. This hierarchy is created by the hand of God, aka the Fed, whose impact on nearly all financial assets and the money market, in particular, is so unmistakable. In this monetary system, a Darwinian inequality, which is determined by how close a country is to the sole issuer of the US dollar, the Fed, is an inherent quality of the system.

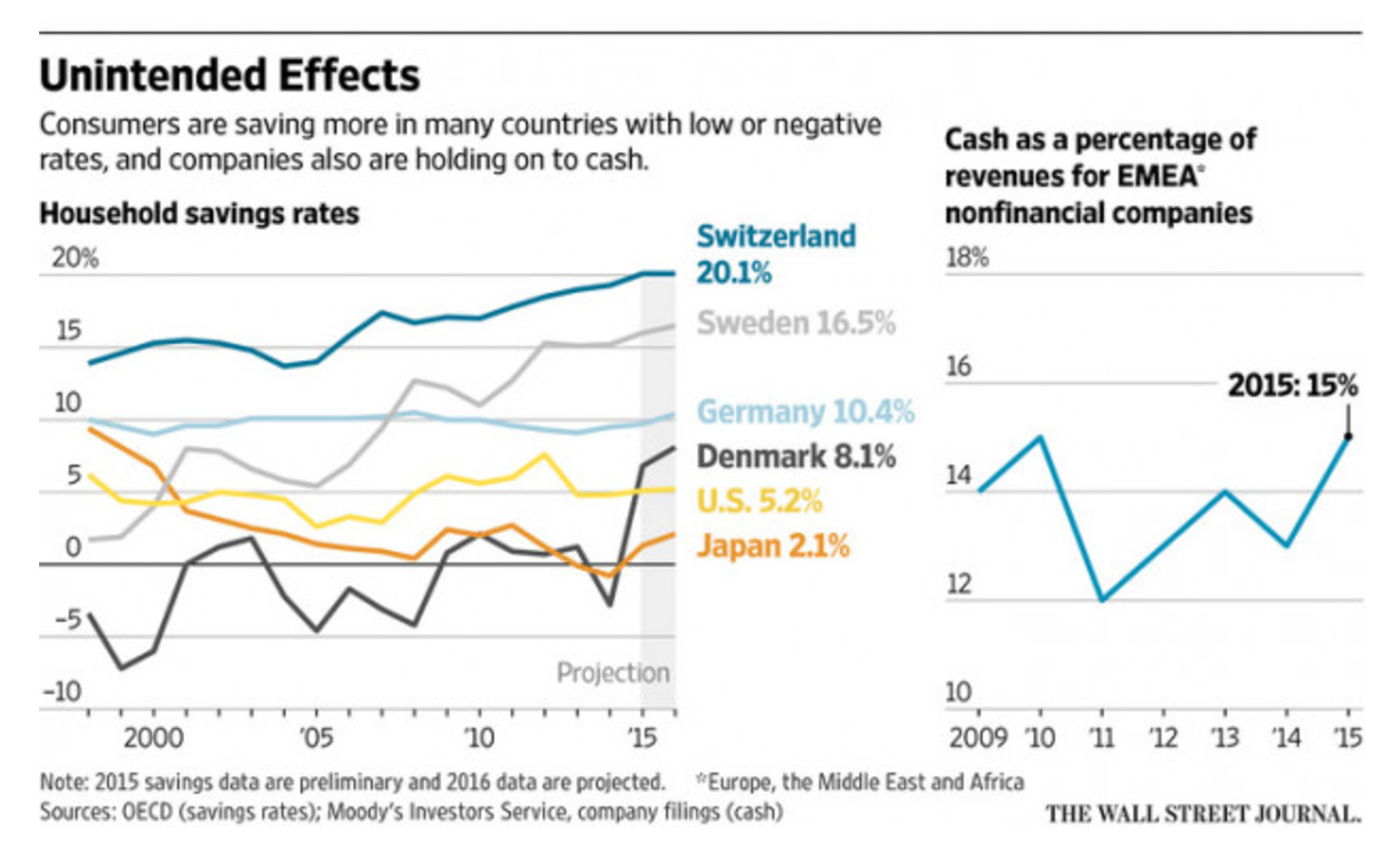

Most of these developments ultimately have their roots in dislocations in the banking system. At the heart of the issue is that a decade after the GFC, the private US Banks are still pulling back from supplying offshore dollar funding. Banks’ reluctance to lend has widened the LIBOR-OIS spread and made the Eurodollar market less attractive. Money market funds are filling the void and becoming the leading providers of dollar funding globally. Consequently, the CP/CD ratio, which measures the cost of borrowing from money market funds, has replaced a bank-centric, LIBOR-OIS spread and has become one of the primary indicators of offshore dollar funding costs.

The market for offshore dollar funding is also facing displacements on the demand side. International investors, including non-US banks, appear to utilize the FX swap market as the primary source of raising dollar funding. Traditionally, the bank-centric market for Eurodollar deposits was the one-stop-shop for these investors. Such a switch has made the FX swap basis, or “the basis,” another significant thermometer for calculating the cost of global dollar funding. This piece shows that this shift of reliance from banks to market-based finance to obtain dollar funding has created odd trends in the dollar funding costs.

Further, in the world of market-based finance, channeling dollars to non-banks is not straightforward as unlike banks, non-banks are not allowed to transact directly with the central bank. Even though the Fed started such a direct relationship through Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility or MMLF, the pandemic revealed that there are attendant difficulties, both in principle and in practice. Banks’ defiance to be stable providers of the dollar funding has created such irregularities in this market and difficulties for the central bankers.

The first peculiar trend in the global dollar funding is that the FX swap basis has continuously remained non-zero after the pandemic, defying the arbitrage condition. The FX swap basis is the difference between the dollar interest rate in the money market and the implied dollar interest rate from the FX swap market where someone borrows dollars by pledging another currency collateral. Arbitrage suggests that any differences between these two rates should be short-lived as there is always an arbitrageur, usually a carry trader, inclined to borrow from the market that offers a low rate and lend in the other market, where the rate is high. The carry trader will earn a nearly risk-free rate in the process. A negative (positive) basis means that borrowing dollars through FX swaps is more expensive (cheaper) than borrowing in the dollar money market.

Even so, the most significant irregularity in the FX swap markets had emerged when the market signaled a US dollar premium and a discount simultaneously. The key to deciphering this complexity is to carefully examine the two interest rates that anchor FX swap pricing. The first component of the FX swap basis reflects the cost of raising dollar funding directly from the banks. In the international monetary system, not all banks are created equal. For the US banks who have direct access to the Fed’s liquidity facilities and a few other high-powered non-US banks, whose national central banks have swap lines with the Fed, the borrowing cost is close to a risk-free interest rate (OIS). At the same time, other non-US banks who do not have any access to the central bank’s dollar liquidity facilities should borrow from the unsecured Eurodollar market, and pay a higher rate, called LIBOR.

As a result, for corporations that do not have credit lines with the banks that are at the top of the hierarchy, borrowing from the banking system might be more expensive than the FX swap market. For these countries, the US dollar trades at a discount in the FX swap market. Contrarily, when banks finance their dollar lending activities at a risk-free rate, the OIS rate, borrowing from banks might be less more expensive for the firms. In this case, the US dollar trades at a premium in the FX swap market. To sum up, how connected, or disconnected, a country’s banking system is to the sole issuer of the dollar, i.e., the Fed, partially determines whether the US dollar funding is cheaper in the money market or the FX swap market.

The other crucial interest rate that anchors FX swap pricing and is at the heart of this anomaly in the FX swap market is the “implied US dollar interest rate in the FX swap market.” This implied rate, as the name suggests, reflects the cost of obtaining dollar funding indirectly. In this case, the firms initially issue non-bank domestic money market instruments, such as commercial papers (CP) or certificates of deposits (CDs), to raise national currency and convert the proceeds to the US dollar. Commercial paper (CP) is a form of short-term unsecured debt commonly issued by banks and non-financial corporations and primarily held by prime money market funds (MMFs). Similarly, certificates of deposit (CDs) are unsecured debt instruments issued by banks and largely held by non-bank investors, including prime MMFs. Both instruments are important sources of funding for international firms, including non-US banks. The economic justification of this approach highly depends on the active presence of Money Market Funds (MMFs), and their ability and willingness, to purchase short-term money market instruments, such as CPs or CDs.

To elaborate on this point, let’s use an example. Let us assume that a Japanese firm wants to raise $750 million. The first strategy is to borrow dollars directly from a Japanese bank that has access to the global dollar funding market. Another competing strategy is to raise this money by issuing yen-denominated commercial paper, and then use those yens as collateral, and swap them for fixed-rate dollars of the same term. The latter approach is only economically viable if there are prime MMFs that are able and willing, to purchase that CP, or CD, that are issued by that firm, at a desirable rate. It also depends on FX swap dealers’ ability and willingness to use its balance sheet to find a party wanting to do the flip side of this swap. If for any reason these prime MMFs decide to withdraw from the CP or CD market, which has been the case after the COVID-19 crisis, then the cost of choosing this strategy to raise dollar funding is unequivocally high for this Japanese firm. This implies that the disruptions in the CP/CD markets, caused by the inability of the MMFs to be the major buyer in these markets, echo globally via the FX swap market.

On the other hand, if prime MMFs continue to supply liquidity by purchasing CPs, raising dollar funding indirectly via the FX swap market becomes an economically attractive solution for our Japanese firm. This is especially true when the regional banks cannot finance their offshore dollar lending activities at the OIS rate and ask for higher rates. In this case, rather than directly going to a bank, a borrower might raise national currency by issuing CP and swap the national currency into fixed-rate dollars in the FX swap market. Quite the contrary, if issuing short-term money market instruments in the domestic financial market is expensive, due to the withdrawal of MMFs from this market, for instance, the investors in that particular region might find the banking system the only viable option to obtain dollar funding even when the bank rates are high. For such countries, the high cost of bank-lending, and the shortage of bank-centric dollar funding, is an essential threat to the monetary stability of the firms, and the domestic monetary system as a whole.

After the COVID-19 crisis, it is like a tug of war emerged between OIS rates and the LIBORs as to which type of interest rate that anchor FX swap pricing. Following the pandemic, the LIBOR-OIS spread widened significantly and this war was intensified. Money View declares the winner, even before the war ends, to be the bankers, and non-bankers, who have direct, or at least secure path to the Fed’s balance sheet. Marcy Stigum, in her seminal book, made it clear not to fight the Fed and emphasized the powerful role of the Federal Reserve in the monetary system! Time and time again, investors have learned that it is fruitless to ignore the Fed’s powerful influence. Yet, some authors put little effort into trying to gain a better understanding of this powerful institution. They see the Fed as too complex, secretive, and mysterious to be readily understood. This list of scholars does not include Money View scholars. In the Money View framework, the US banks that have access to the Fed’s balance sheet are at the highest layer of the private banking hierarchy. Following them are a few non-US banks that have indirect access to the Fed’s swap lines through their national central bank. For the rest of the world, having access to the world reserve currency only depends on the mercy of the Gods.

Elham Saeidinezhad is lecturer in Economics at UCLA. Before joining the Economics Department at UCLA, she was a research economist in International Finance and Macroeconomics research group at Milken Institute, Santa Monica, where she investigated the post-crisis structural changes in the capital market as a result of macroprudential regulations. Before that, she was a postdoctoral fellow at INET, working closely with Prof. Perry Mehrling and studying his “Money View”. Elham obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Sheffield, UK, in empirical Macroeconomics in 2013. You may contact Elham via the Young Scholars Directory