Most of us have an idea of how money came to be. It goes something like this: People wanted to exchange goods for other goods, but it was difficult to coordinate. So they started exchanging goods for money, and money for goods. This tells us that money is a medium of exchange. It’s a nice and simple story. The problem is that it may not be true. We may be understanding money entirely wrong. Continue reading “The History of Money: Not What You Think”

Can we Learn from Minsky Before the Next Crisis?

Earlier this month I had a conversation with a regional manager from a major insurance company. She explained to me the many aspects of her industry: the commission based salaries, strategies to sell life insurance to one year-old children, and how to retain employees. To be honest, I don’t find insurance to be the most riveting topic out there, but I did have a question I wanted answered: What does her company do with the money their clients pay for their insurance packages? Her response surprised me for its candor, she said:

- “You know, insurance companies don’t make their money from premiums and things like that anymore. Most profits come from investing in the stock market.”

We truly are in the era, as Minsky called it, of money manager capitalism. What this means is that insurance companies are no longer in the business of insurance, they are just another player in the financial markets; the only thing that differs is how they get their capital. Combine that with the fact that many of their employees have their entire pay check dependent on commissions and we have companies that are trying to sell as many policies as possible – sometimes to people who do not need it or can’t afford it – in order to have more capital for financial investments.

If that sounds familiar it is because those are the kind of practices (while obviously not the only one) that led to the Great Recession and specifically to the crash of insurance giant AIG (which was bailed out with 182 billion dollars). It is, to say the least, disheartening to see that those practices are still in place by insurers and elsewhere, but it is hardly surprising. To know why we must turn to Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis.

The Hypothesis is possibly the most notable part of Minsky’s extensive work, it is indeed brilliant in its accuracy and simplicity. Nevertheless, it seems to escape from the spotlight of economics and politics in an counter-cyclical manner: every time the economy does well, people seem to forget about it – but during the crisis his book Stabilizing an Unstable Economy went from costing less than 20 dollars, to over 800 (that is, if you could find it). Another example, The Economist had only mentioned him once while Minsky was alive, but since the 2007 crisis his ideas have appeared in over 30 of their articles. As the British newspaper puts it, “it remained until 2007, when the subprime-mortgage crisis erupted in America. Suddenly, it seemed that everyone was turning to his writings as they tried to make sense of the mayhem.” Therein lies the irony, it is exactly when the economy is booming that we should pay the most attention to the Financial Instability Hypothesis.

In short, Minsky postulated that stability is destabilizing, as Oscar Valdes-Viera has awesomely explained before in this blog. In his post, Oscar tells us to be skeptical of politicians who say the economy is doing well; that is when individuals and institutions are moving from hedge, to speculative, to Ponzi positions. In most cases, economic actors will become eerie of risk after a crisis and shun from risky investments such as CDOs. It seems, however, that this aversion to risk has not happened. One can speculate many reasons for this behavior, among which is the bailing-out of so called “Too-Big-to-Fail ” organizations.

As such, it is clear that although Minsky’s popularity increased during the last crisis, the people making important financial decision did not learn from his work. The problem of irresponsible behavior and borderline fraudulent financial innovations still remain. It is time to enact on a less popular, although still important, part of Minsky’s work: the “Big Bank”. That bank, naturally, is the Fed and it plays a number of roles: it sets interest rates, it regulates and supervises banks, and it acts as lender of last resort. However, as Randall Wray explains in a 2011 paper, “most Fed policy over the postwar period involved reducing regulation and supervision, promoting the natural transition to financial fragility.”

Case and point, the SEC and the IRS had their budget severely cut in 2014 and do not currently have the capacity effectively regulate the financial industry. To make matters worse, shadow banks and traditional banks – as demonstrated anecdotally by my conversation with the insurance agency manager – still intermingle in financial innovations. Common sense dictates that after the 2008 crisis companies should have reset to the more sustainable and safer hedge position, but it seems that many financial actors went right back to the more unsustainable speculative position after the crash. One could also have expected that financial jobs would decline in popularity post-2008, but the opposite has occurred; finance as an industry now takes 25% of corporate profits, but only makes up 4% of jobs in the US. The rising importance of the finance industry has other adverse effects besides increasing the possibility of crisis, it means that companies are not investing in producing real output for they can earn more by playing the markets.

Hence is the place in which we found the economy: misguided policy has created a weak regulatory environment where irresponsible risk-taking is ‘insured’ by the precedent set by bail outs, and where even the highest ever levels of liquidity do not lead to real investment and a strong economy. This bad omens have inspired many economists to declare that a crisis is coming. Add to that the fact that recently Minsky has been featured in mainstream media sources like The Economist, and that his seminal book in financial instability was recently the number one best seller on Amazon for Public Finance, and one has reason to feel a bit uneasy about the coming year.

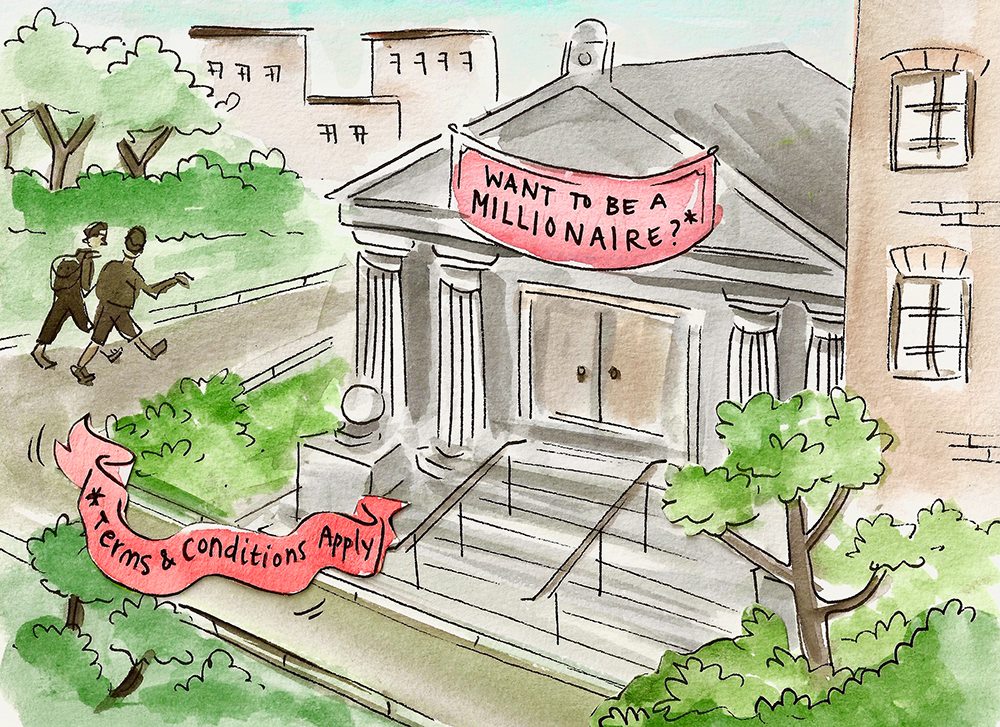

Should Everyone Go To College?

On the first day of the Democratic National Committee we heard Bernie talk about how the new Democratic platform will allow children in any family making less than $125,000 a year to go to a public college or university tuition free, while substantially reducing student debt. This is a big win for the platform, and evidence that Bernie forced Hillary left.

Meanwhile, Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors released a report arguing that the $1.3 trillion in student debt is helping, not hurting, the US economy. They argue it is helping relative to a baseline where people would not attend college if not given access to loans to get there. They come to this conclusion using lifetime earnings models to show that on average someone with a bachelor’s degree makes $1 million more than someone without it. This then outweighs the costs of their student debt. If student debt levels rose to $500,000 for a college education, however, their argument still holds.

The thing is, the economy would be doing even better without the massive debt burden placed on our young people. As Nick Cassella of Civic Skunk Works argues, framing education like they do reveals their preference to view a college education as an investment rather than a right. It also frames a four year bachelor’s degree as “the” college education, rather than helping students to understand all the options available. As sociologist James Rosenbaum highlights, high schools and community colleges encourage almost exclusively four year bachelor degree programs to their students. This downplays important certifications and associate’s degrees. If a bachelor’s degree is a right, a public investment we believe all citizens should have, then it should be available for free without debt. If it is merely an individual investment, than it should not be promoted as the solution for everyone. The highest volume of in demand jobs today do not require a four year bachelor’s degree.

The interplay of education and job access highlights the two, sometimes not overlapping, goals of higher education housed into one institution: educating our population, and training our workforce. This has been an institutional feature of the American system for some time, noted by socio-economist Thorstein Veblen in his 1918 piece The Higher Learning in America. William Deresiewicz, in his book Excellent Sheep, recounts his time at Yale and the stories he saw of youth conflicted between these two goals. Students are taught to be active engaged citizens, which for some would involve teaching and public service, yet careers on Wall Street and in big private sector firms are the ones that allow them to payoff their debts faster and make college “worth it”. Framing college as an investment discounts the true value of an education. Pushing students to take on debt to get their degrees also forces this view of college as a monetary investment rather than an investment in education. Even when it is framed as an investment, it does not payoff the same for everyone. While averaging across all bachelor’s degrees you get a million dollar payoff, those lifetime earnings are not distributed equally among all graduates. Using the 2014 ACS, I calculate that the average income of a white person with a bachelor’s degree is $63,000 versus $48,000 for a black person. The St. Louis Fed shows that racial wealth gaps still exist despite college degrees. Even the CEA report says “ten percent of workers age 35 to 44 with a bachelor’s degree had earnings under $20,000, compared to 25 percent of workers with only a high school diploma.” As an investment then, it pays off the most for those who can already afford it.

If the goal of the university system is to educate our population, then it should be a right for everyone. John Adams said that “the whole people must take upon themselves the education of the whole people, and must be willing to bear the expense of it.” If our definition of educated continues to mean a four year bachelor’s degree, we must bear that public expense and not put it on students through debt. However, if we can accept educated to be at a high school level, then we can stop the college for all rhetoric and help students better understand the demand side of the economy. For every 2 jobs that require a bachelor’s degree, there are 7 that require a certification. FRED shows 5.5 million job openings today in America. Close to a million are in healthcare and social assistance, half a million are in manufacturing and construction, and around 760,000 are in the leisure and hospitality industry. Most jobs in these industries only require associate’s degrees, certifications, or high-school educations with on the job training. These are good jobs. We need social workers, nurses, plumbers and electricians, and these jobs do not require four year bachelor’s degrees. As Rosenbaum argues “the real goal should not be the unrealistic vision of everyone becoming a doctor, but rather the elimination of the all too common outcome of youths facing dead-end jobs and unemployment as their only options.” Yet 5.5 million job openings does not come close to the over 17 million unemployed according to official unemployment numbers. When there just aren’t enough jobs to go around, we should not be encouraging our citizens to take on high levels of student debt.

Rather than suggesting workers take on debt to be “trained” for the workforce, we should focus on creating jobs that pay workers to learn valuable skills. As Minsky said, “it has never been shown that a thorough program of job creation, taking people as they are, will not, by itself, eliminate a large part of the poverty that exists.” A bachelor’s degree is not a blanket guarantee to a better life, so if we believe in having a more educated population it should be a right as the Democrats are now arguing for. If it is purely meant to be thought of as a monetary investment in training yourself for the workforce, then by looking at the demand side we see that it is clearly not for everyone. John Adams said that “laws for the liberal education of youth, especially of the lower class of people, are so extremely wise and useful, that, to a humane and generous mind, no expense for this purpose would be thought extravagant.” This education need not be a four year bachelor’s degree, but I think it should be. As it is today, we need to make sure young people are aware of all the options available in the economy, and only straddle themselves with debt if they truly will benefit from it. Getting rid of student debt for public bachelor’s degrees allows us all to benefit from having a more educated population. Without large amounts of debt to worry about, student’s can focus on learning for four more years. We have the rest of our lives to work.

Written by Bradley Voracek

Illustration by Heske van Doornen

State of the Unions in the US Economy

Debates about the disappearance of the middle class and the lack of opportunities for the majority of Americans have been at the forefront of the 2016 presidential election. However, discourse surrounding unions and ways to increase the bargaining power of workers are often overlooked in these discussions.

These are integral components of the issue that could enhance the current economic climate for the middle class, and especially benefit low-wage, minority, and immigrant workers. Without unions, employees can be fired at-will in most states and have no collective leverage to negotiate with employers over their most basic terms and conditions. There are almost 15 million union workers across the country who have these rights, and therefore benefit considerably from better wages and working conditions. Here are four ways unions make a difference.

1. Unions benefit workers—especially women and minorities—through the union wage premium,according to data from the Current Population Survey.

- Collective bargaining gives union members wage advantages over nonunion workers, despite holding the same jobs and sharing similar characteristics (e.g. education level, age, race, gender). This is called a union wage premium. On average, union members commanded a 26 percent wage premium in 2015.

- Women tend to have considerably higher union wage premiums than men. In 2015, they made about 33 percent more than their nonunion counterparts, on average, while the union wage premium for men was approximately 17 percent. Unions are also offering another advantage through helping to close the gender pay gap.

- Minorities have also shown to have better economic outcomes when they belong to unions. As of 2015, average Hispanic full-time workers’ weekly earnings were 47 percent higher when they were part of a union. The typical African-American worker received a 30 percent union wage premium.

2. Unions not only push for higher wages, but their members also tend to obtain more comprehensive benefits. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, union workers are more likely to have access to health insurance, as well as have retirement plans and paid sick leave.

- This is especially important for immigrant workers and employees in low-wage jobs. The Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) finds that immigrant workers who are union members have close to a 50 percent higher chance of having employer-provided health insurance, and twice the probability of having a retirement plan. Union workers in low-paying jobs have a 25 percent higher probability of having these benefits.

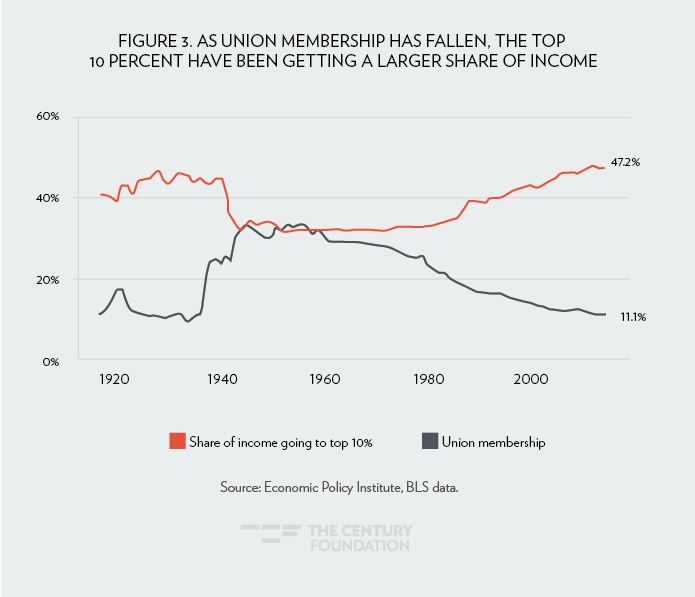

3. Unions fight to maintain an equitable distribution of income among employers and workers.

- It is no coincidence that the percent of income going to the top percent of earners has increased while union membership has declined. The erosion of collective bargain reduces the share of income going to American families in the middle of the income distribution—not only union members. That is because unions pull millions of non-union Americans into the middle class by setting higher compensation standards that push everyone’s wages up. The decline of the middle class is, therefore, directly related to the decline in the density of unions.

- The shrinking middle class has resulted in less spending money for many American families. Considering that household consumption is the main engine of our economy—accounting for around 70 percent of GDP—when the majority of workers can’t afford to spend the economy stagnates. Thus, contrary to popular opinion, unions do not impede economic growth when they fight for labor to receive its fair share of income, they are actually necessary to maintain a strong economy.

4. Unions are crucial for democracy.

- As a recent Century Foundation report explains, unions serve as counterbalancing influences to arbitrary government powers. They function as “schools of democracy” for workers and help maintain a public education system that fosters democratic values. For example, the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Associationsuccessfully advocated to revitalize the school curriculum to include issues surrounding civic engagement. Unions also represent one of the largest forms of an organized voice for low and moderate income Americans. In short, strong unions could ensure that society does not become governed by a small number of wealthy individuals.

So Why Are Union Membership Rates So Low?

Although there is overwhelming data showing the benefits of unions, they are battling to maintain their crucial foothold in the economy, especially in the private sector.

According to data from the Current Population Survey, unions remain strong in the public sector, with more than one-third of employees identifying as union members. Not surprisingly, the public sector employs more minorities and provides more equal wages than the private sector. The professions with the strongest unions include teachers, police officers, and firefighters.

However, workers in the private sector are over five times less likely to participate in unions, with membership rates down to 6.7 percent.

The decline in union participation in the private sector has dragged down the total union membership rate. However, thanks to strong public sector unions, the rate of decline has stagnated in recent years, remaining at 11.1 percent since 2014.

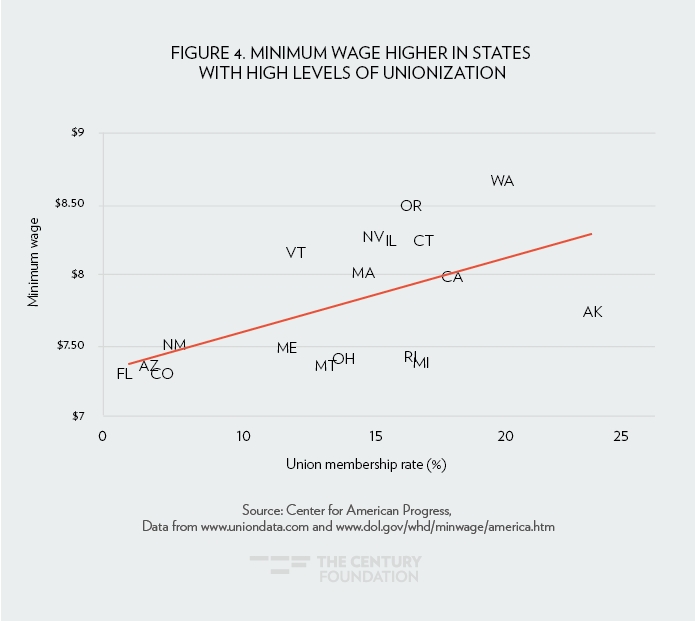

Among states, New York has had the highest percent of union members with 24.7 percent in 2015. South Carolina has been on the other end of the stick, with only 2.1 percent of full-time workers belonging to a union. Examining the breakdown of union workers by state reflects the impact unions can have on lifting the wage floor for all citizens. States with higher union density tend to have a higherminimum wage for union and nonunion workers alike.

Even though polls show that close to 60 percent of workers see unions favorably, structural barriers have been holding back organizations from embracing unions.

The election process to establish a union, governed by federal law (National Labor Relations Act), puts major barriers in place for workers who want to become members. Even when workers want to be part of a union, they are typically harassed and can find themselves illegally fired. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) maintains that workers have the right to “form, join or assist a union.” However, the CEPR found there has been a steep rise in illegal firings of pro-union workers in the 2000s compared to the previous decade. Employers have a variety of unfair labor tactics they have used in union organizing drives—like hiring anti-union consultants (a $4 billion-a-year industry) or spying on their workers. However, minimal penalties and slow enforcement disincentivize companies from following the law. For example, two of the biggest employers in the U.S.—McDonald’s and Walmart—have been targets of such lawsuits but have rarely faced significant enough repercussions to dissuade them from continuing to employ these practices.

Another obstacle to establishing unions have been the Right-to-Work (RTW) laws, which are estimated to reduce union membership rates by 8.8-9.6 percent. With the addition of Wisconsin and West Virginia in the past two years, twenty-six states now have RTW laws. Under RTW state laws, companies can’t lawfully agree to agency shop, which allows workers to receive benefits secured by unions without contributing to cover collective bargain costs. The lack of agency shop cripples unions, and dissuades those interested in organizing drives.

Proponents of RTW argue these laws foster economic growth by raising competitiveness and attracting more business into their states. However, these laws promote economic growth by supplying their citizens labor at the cheapest price, instead of promoting and creating higher wage jobs. Workers in RTW states, which are most common in the South, are estimated to make $1,558 less per year, on average.

How Are Unions Responding?

Unions and their allies are developing new strategies to overcome these challenges and build alternative forms of workers bargaining.

A first priority has been strengthening labor laws and access to unions. Promising developments include the WAGE Act introduced last year that would extend civil rights laws to workers in unions. And, an emboldened National Labor Relations Act has put in place new rules to make elections faster and to make it easier to organize workplaces, like McDonald’s, that are jointly owned by a main company and numerous franchise.

In response to the limitations of firm-by-firm bargaining, unions are mounting cross-industry, cross-state campaigns to uplift the working conditions of all workers. The Fight for $15 movement is bringing together thousands of workers to demand a $15 minimum wage,which has already been implemented for workers in Seattle,New York, and California.

Unions are also partnering with alternative labor organizations, like workers centers, to provide support to workers—mainly people of color, immigrants, and low-wage workers but also those in the patchwork economy—that do not have access to union

representation.

By Oscar Valdes-Viera

Illustration by Heske van Doornen

This piece was originally published (here) by The Century Foundation in New York.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership, Trade Deals and Income Inequality

When Oxfam’s 2016 Davos Report revealed that 62 people own half of the global wealth many were shocked by this finding and attributed it to high poverty levels in low-income countries. However, wealth inequality is also a problem in rich countries like the US. The OECD found that the wealthiest 10% of US households own 76% of the total wealth, while those at the bottom 40% of the distribution have no wealth at all. To make matters worse, the 2008 Great Recession wiped out the wealth of many American families, and they failed to regain it in the ensuing recovery. Research done by Levy Institute’s Pavlina Tcherneva found that in the aftermath of the Great Recession, real incomes of those in the bottom 90% of the US income distribution have fallen, while those in the top 10% have enjoyed all the gains of the recovery.

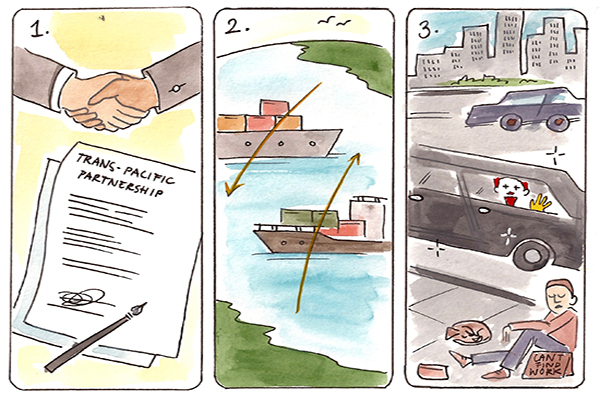

These trends are the result of neoliberal “free-market” policies implemented since the 80s, which emphasized tax cuts, deregulation, and weakening of labor protections, all under the guise of increasing efficiency. Trade deals, while not the sole culprit, have played an important part in the downward pressure on wages for American workers and the loss of numerous domestic manufacturing jobs. The rise in global trade has created severe competition for many American workers, many of whom have lost their jobs or been forced to accept pay cuts. Trade agreements put in place by the US offer corporations the necessary legal protections to safely relocate their business overseas. While proponents of trade agreements continue to insist these will create new jobs for American workers, the opposite has been true. For example, the Economic Policy Institute estimates that almost 700,000 jobs have been lost as result of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), despite it promising to create 200,000 new jobs for American workers.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an agreement between 12 countries, which together make up for 40% of world trade, is considered by Obama a key element of his legacy and follows a “pro-market” approach similar to most policies of the neoliberal era. This pact will eliminate tariffs, and impose and enforce stronger patent protections overseas while also reducing restrictions for tech companies to enter foreign markets. Obama’s administration promises the deal will “level the playing field for American workers & American businesses,” and “strengthen the American middle class.” However, a closer reading of the provisions of the agreement offers a different interpretation. The TPP will strengthen the power of multinational corporations, expand their influence over governments, and increase profit margins at the expense of American workers.

Amongst the most concerning provisions of the TPP is one that gives corporations an easy path towards suing governments and thus undermining their sovereignty. The treaty agrees to establish an Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS), through which corporations can challenge domestic laws in countries that are part of the TPP. These challenges would be resolved through arbitration, rather than traditional courts. The arbitration process is led by panels composed of three corporate lawyers, only one of whom is government appointed. As Elizabeth Warren warned in this Op-Ed, the provision “would allow big multinationals to weaken labor and environmental rules.”

Those arguing in favor of the TPP claim it will allow the US to write the rules on how trade with Asia should be conducted. Yet this argument fails to mention that it’s American corporate interests that will write the rules. Free trade with the countries participating in the TPP is already established, and this agreement does not open up new opportunities for trade; rather it sets the terms in favor of business interests. The TPP will further erode bargaining power of American workers, who will face increased legal scrutiny over protections they enjoy. By solidifying the legal power corporations enjoy abroad, the agreement will facilitate smooth relocation and outsourcing of more and more jobs. This additional threat to job security for American workers will increase downward pressure on their wages, while the profits of corporations will grow, thus upholding the trend of rising income inequality. It is not a coincidence that as the global influence of corporations increases, so does disparity of wealth.

The positive impacts the TPP might have on the economy would be absorbed by the wealthy, while average American workers would suffer the negative consequences. The TPP protects large multinational corporations; yet offer few safeguards for lower-skilled domestic workers. Overall, it is reasonable to argue that the TPP would only further exacerbate income inequality by tilting the balance even further in favor of big companies. However, it is also unrealistic to argue that by rejecting the TPP and other trade agreements the US can bring back all the manufacturing jobs it lost.

American policymakers need to realize that it is vital to draft agreements that take into account the needs of working people, and not just of corporations; that there is an active need for policies that can once again strengthen the American middle class. Otherwise, the discontent of workers who continue to see their incomes decline and job prospects worsen will allow fringe candidates such as Donald Trump, who foster racist and xenophobic rhetoric, to rise to power. Although the solutions offered by Trump make little economic sense, he gains in popularity by recognizing that American workers have been disadvantaged by various trade deals.

It is urgent for policymakers to stop pushing for policies that expand income inequality, and to look for strategies to reverse this trend. In the late 1970s full employment was abandoned as a policy goal, labor protections were eroded, finance deregulated, and taxes for the wealthy reduced. Seeing the consequences of these changes in the falling living standards of most Americans and exploding income inequality, it is time to take action and work to rolling back these policies. Pushing for more agreements amongst those same lines, such as the TPP, will only make matters worse.

By Lara Merling

Illustration by Heske van Doornen

Class Interests & Discordant Politics: Brexit & the Trump Campaign

The shortcomings and false promises of mainstream economics are impossible to ignore in the context of the Brexit vote and Trump’s success in the Republican primaries, with working and middle class individuals in both the UK and the US clinging to some promise of socio-economic salvation. Lately, we’ve seen an especially pronounced disconnect between political parties and the social classes they respectively govern. These instances of political manipulation have similar dynamics: the key is to cultivate an image of the far right’s intentions that suggest they are aligned with class interests, only to pursue methods that further marginalize their own supporters. And when their policies inevitably fail and it’s time to place blame, who bears the brunt of it all? Immigrants.

But, I digress. Let’s talk neoliberal restructuring to set the stage. You know, that period that began in the 70’s where the US and the UK experienced pronounced economic stagnation. When stagflation set in, who better to blame than those damn liberals and the economic policies of the welfare state they induced (am I right, Reagan)? The resentful rhetoric propagated by Reagan and Thatcher suggested that such policies created “welfare queens” looking to loot the government for all they’ve got (just when mainstream economics had me convinced these were the self-interested economic actors dreamed up by the neoclassical synthesis). The ascent of conservative capitalism- in the US under Reagan and George Bush Sr. and in the UK under Thatcher- meant tax cuts, the erosion of labor unions, and new regulations imposed on the economy. These economic regime changes were based on the mainstream theoretical presupposition that what we really needed to do was create an economic environment conducive to unbarred corporate innovation and investment and eagerly accept international policy which, together, opened the proverbial floodgates allowing neoliberalism to leak all over the globe. What a mess.

Free trade agreements, like The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), and the emergence of the World Trade Organization allowed labor and capital mobility across borders. Interestingly, the majority of Democrats and Labor party folks alike took no issue with such policies-not under Clinton, not under Blair, not even under Obama. Obama, in fact, unfortunately followed the policy-tide of the bank-bailout Bush administration- the very administration that watched middle and working class American homeowners drown financially (but sure, save the banks)- before him. Post-2008 financial crisis, Obama supported the Trans Pacific Partnership, which certainly aids the perpetuation and spread of Neoliberalist influence. While Obama has made modest strides in terms of challenging the Neoliberal economic scheme- enduring the constant stymie of the republican party- his approaches to socio-economic issues have been predominantly market centered (e.g., Dodd Frank, ACA, etc.). The economic and political quintessence of neoliberalism remains unfettered. As a parallel, the Labor Party actively attempted to defend minorities, but did very little to keep the UK in the EU and have also struggled to directly address neoliberalism.

Unfortunately, the general population of U.S. and the dominant political parties of Europe have bought the story of neoliberalism told by our paternalistic politicians. They convinced the majority that the continuation of this approach is what’s best for them. Meanwhile, the working class suffered and the middle class disappeared; but how? Aren’t we all being provided the greatest possible economic good? Mainstream preachers of Pareto Optimality – a scenario where economic actors can improve their position without disadvantaging/compromising the position of another economic actor- imply the changes that come out of neoliberalism (that of the economic structure, the promotion of free trade and globalization, etc.) should be “efficient;” the loss of some jobs in domestic goods production would be neutralized by the trade stimulus, right?

Wrong. The myth of trickle-down economics proved itself, well, mythological. We’ve seen surging inequality, static wage growth over the last four decades, and disappearing jobs in manufacturing (a 37% decrease in the number of manufacturing jobs since 1979, as per the BLS). These are all hindrances to working and middle class Americans. They paid for neoliberal restructuring only to be denied the prospect of economic security and benefit which induced them to submit to such a socio-economic and political climate.

At the same time, we watched Bush and Blair start politically chaos with Bush’s War on Terror- again, an unrequested paternalistic move that subverted and unsettled the Middle East (note: not a monolith) and provoked an occidental response (well, duh), thus designing an ideal birthplace for ISIS. We’ve seen the Syrian crisis displace millions of Syrians- refugees sprawled across European nations with unequal access to livelihood.

Trump enters the race (and unfortunately the hearts of far too many Americans) and Britain exits the EU. We’ve seen neoliberalism literally create the “problem” Trump has convinced many Americans we have; Mexico’s economic instability is arguably due to the effects of NAFTA and to escape poverty, many immigrate to the US in search of employment. Low-skill working class whites perceive additional threats to their already delicate economic standing-posed by people of color at that- and suddenly the existing issues built by neoliberalist restructuring are not the problem.

The Leave campaign and Trump have hacked the interests of UK and US low-skilled working class white individuals, who blame immigrants for their job losses. These individuals really lost their jobs because of neoliberalist restructuring as free trade moved manufacturing jobs overseas, while simultaneously causing economic insecurity in nations like Mexico, thereby motivating immigration. By creating and playing on the sentimentalism attached to xenophobia, patriotism/nationalism, religion, racism, and lack of economic confidence (all bound up with one another, by the way) caused by neoliberalist restructuring, Trump and the UK’s Independence Party became the “saviors” with class interests at the heart of their intentions. This is undoubtedly a self-reinforcing mechanism. Their manipulation continues to reap them undue success and secure mass appeal. It is only suitable that the last 30-40 years of the Right wing utilizing racism and the conflict between traditionalist and progressive values has culminated into the likes of a Trump candidacy and the Leave campaign. These are merely the current guise of the neoliberal economic agenda, still hell-bent on toiling any hope for socio-economic equity.

The moral of the story? If we, presumably progressives and proponents of heterodoxy, seek to challenge the social constructions which contribute to economic instability, rising inequality, unjust wage structure, and a labor force altered by free trade like racism and harmful traditionalist notions, we cannot let the underlying perpetuity of neoliberalism go unaddressed. Working and middle class individuals will only continue to act against their class interests. Workers will continue to feel hopeless. Wages will continue to stagnate and jobs to disappear. This cycle will continue as long as we allow a power-serving social, economic, and political climate- that says rejecting the establishment in the form of racism, xenophobia, and overt nationalism is the solution to their problems- to persist.

Written by Daniella Medina

Illustrations by Heske van Doornen

The Job Guarantee: The Coolest Economic Policy You’ve Never Heard Of

When you think of economic issues what are the first things that come to mind? Poverty, inequality, unemployment, inflation, and crisis are all common answers to the question. Wouldn’t it be great if there was a policy that could address all of those issues (and more) in a cost-effective manner? In this piece I will give a very brief introduction to Job Guarantee (JG) schemes, the proverbial economic silver bullet.

Hyperboles aside, Job Guarantee proposals (which may come in many different names such as Employer of Last Resort, or Public Service Employment) are a remarkably good way to address many of the social economic problems current faced by populations all over the world. Ideas about JG programs date back to as early as the 1600s, they have been implemented in many nations during a variety of different stages of the business cycle – and usually to a great deal of success.

Simply put, JG is a direct public employment policy where all of those people who are willing and able to work are guaranteed a job given that these individuals meet some basic employability requirements. Most proponents of JG establish that these jobs should pay a basic, fixed, uniform wage plus full medical coverage and free child care (the latter can be provided by JG workers themselves). The goal of the program should be to ensure that all full-time JG workers are able to obtain a living standard that is above a reasonable poverty threshold. Thus, this sort of program go a long way in addressing poverty. Furthermore, it would also target another major economic problem, the stagnation of real wages and the currently low minimum wage granted to US workers. The JG wage would instantly become the minimum wage for the entire economy: workers in other sectors that are receiving less than the JG wage would be very compelled to take one of those guaranteed jobs, and employers would have to raise their salary offers in order to keep their workforce. Finally, the wages would also act as price anchor, which improves upon the stability of the economy.

The first question I usually get when telling someone about the Job Guarantee is “yeah but, how can we afford it?!” Questions about the deficit and national debt have been put to rest previously on this blog (see here), hence I shall focus on other questions regarding its affordability. For starters, it has been shown elsewhere that JG is remarkably cheaper and more effective than other proposals, such as Basic Income and Negative Income Tax, in achieving lower poverty and unemployment rates (see here, and in many pieces by Rutger’s Phillip Harvey). Secondly, the newly employed JG workers would bring in savings in many different ways: they would get out of unemployment insurance, food-stamps, and other such programs; they will pay income tax, medicare and social security tax, as well as more consumption related taxes; and the government would spend less on issues that are related to poverty, such as higher crime rates. In addition, employment multipliers would make it so the JG program would not have to employ the entire unemployed population. The extra consumption and production related to the JG will create indirect and induced jobs which will represent a significant portion of the job creation from the program. Finally, yours truly is among a number of economists who have modeled the implementation of a a JG for the US and found that eliminating unemployment at a living wage would cost just around 1% of the American GDP.

At this point many say something like “but employing everyone while raising the minimum wage has to be inflationary!” the answer to which is a simple “nope”. First, we have to bear in mind that in the current system the economy’s most precious resource – workers – is being wasted in unemployment, while under a JG program it will be put to use. Orthodox economic thought claims that millions of people need to be unemployed in order to contain inflation, that it is financially “sound” to a tenth of the population in idleness for an unknown period of time. It comes from the idea that the economy is always operating at full capacity, which then brings the inflation problem to being a matter of equilibrating the demand and supply forces of the economy. Both of these assertions are, to quote Keynes, “crazily improbable – the sort of thing that which no man could believe had not his head fuddled with nonsense for years and years.” Government expenditure is as inflationary as any other sector expenditure. Unemployed workers are spending in consumption either way, being sustained by welfare or, dangerously, by credit – and there’s nothing financially “sound” about that.

A JG program would in fact control for inflation by proving a minimum wage anchor for prices and by increasing the productive capacity of the economy through its projects. It would take off the pressure put on demand from the unemployed by increasing supply of goods and services by incorporating those idle workers in the productive structure. Furthermore, even if we assume it to be inflationary it would be a “one-time” increase in inflation, and not an accelerating type one, meaning that demand (and inflation) wouldn’t rise above the full employment level.

In that sense, the costs associated with a JG program (increasing budget deficit and inflation) are not more than ideological myths that obscure the true social costs of unemployment and poverty and curtails any innovative attempts to deal with them. Indeed, generating aggregate demand, employment and inflation is all what the US economy has tried to do since the 2008 financial crisis, but through the wrong ways. A JG program would be extremely more efficient and less costly than QE or negative interest rates. As the world crumbles in economic and political instability, guaranteeing jobs would surely deal with most of its problems. It is up to governments to load and shoot that silver bullet. I don’t think there’s a more appropriate time than now.

Written by Carlos Maciel & Vitor Mello

Illustrations by Heske van Doornen

Carbon Trading, Sustainable Development and Financial Fragility

The response to climate change is one of the most pressing policy issues of our time. Carbon trading assets are currently worth more than $100 billion. This market is expected to reach $3 trillion by 2020. In Stabilizing an Unstable Economy Hyman Minsky notes that the markets for financial assets are inherently unstable, leading to the cyclical behavior of the economic system. How effective then are market-based solutions to solving climate change? It might just be that carbon markets have not reduced environmental instability and may increase financial instability of the entire economic system.

The core of carbon trading isnot trading of physical GHGs, but the trading of the right to emit GHGs and the unit of account is a ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e). The carbon market stems from the Kyoto Protocol, and its specifics are target of discussion as scholars debate about the legal characteristics of the carbon unit. Some countries view it as a commodity while others see it as a monetary currency.

Under the Kyoto Protocol trading mechanisms were made up of three types: international emissions trading, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), and Joint Implementation (JI). The European Union Emission Trading System (EU ETS) is the world’s largest carbon market. According to the 2016 ICAP worldwide emissions report, there are 17 emissions trading systems operating around the world, which are currently pricing more than four billion tons of GHG emissions. In 2017, two new systems will be launched: China and Ontario, the former will become the largest of such systems, and will drive worldwide coverage of ETSs to reach seven billion tons of emissions by 2017.

Voluntary markets exchanges (carbon markets outside the Kyoto) are also on the rise because they make trading, hedging and risk management easier by providing liquidity. Furthermore, they develop sophisticated financial instruments such as CER futures, options, and swaps, which will help establish a price forecast for carbon. Some of these markets are the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX), Multi-Commodity Exchange of India (MCX), and Asian Carbon Trade Exchange.

Sustainable Development

From their foundation, carbon markets have failed to address the underlying root causes of climate change. They divert money from technological investment that will actually reduce the use of fossil fuels towards the financial markets. Furthermore, they are causing instability in the environment through the use of carbon offsets, which have caused massive green grabs to occur in the global South, and through outsourcing emissions to developing nations. Carbon offsets were created by Kyoto to describe emissions reductions projects that are not covered by an ETS. For instance, tree plantations, fuel switches, wind farms, hydroelectric dams…etc.

The world’s richest have over-consumed the planet to the brink of ecological disaster. Instead of reducing emissions within their own countries, they have created a carbon dump in poorer regions. As such, emissions trading system represent the world’s greatest privatization of a natural asset. The Kyoto protocol is set up in a way that carbon sink projects (forests, oceans, etc.) are only accepted when people with official status manage them. Hence, it expands the potential for neocolonial land-grabbing to occur. Rainforest inhabited by indigenous people will only qualify as “managed” under the Kyoto when they are run by the state or a registered private company.

Furthermore, carbon trading has also failed to reduce global GHGs emissions. When a country claims to have reduced its carbon emissions, one must question whether it is by adopting low-carbon technologies, like how Sweden used well-crafted public policies and market incentives to decarbonization, or by outsourcing its emissions to another country, most likely to developing nations. For example, the Chinese government has questioned whether the emissions coming out of Chinese smokestacks were really ‘Chinese’ or should they be accounted to those in Western countries who are consuming Chinese goods or are owned by joint venues with developed countries. The question arose because Europe claimed that it was making progress on climate change based on tabulating the physical locations of molecules. Larry Lohmann phrased it perfectly when he said that Europe’s statistical claim “[conceal[s] an important fact that it has offshored much of its emissions [to China].” Take the UK, it has not in fact reduced its emissions it merely offshored one-third of its emissions by not accounting for emissions of imported goods and international travel.

Carbon markets have had many fraudulent activities within them. In 2002, the UK had a trial emissions trading scheme worth £215 million, which resulted in fraud. Three chemical corporations had been given £93 million in incentives when they had already met their reduction target. Another famous fraudulent activity revolved around international offset projects whereby companies would create GHGs just to destroy them and make money off of the credits.

As nature is being commodified and privatized,the current policies for sustainable development, under the guise of conservation, are alienating the poor from their means of livelihood by securing resources for organizations. These indigenous people — land users — are seen as needing to be saved from their primitive ways and to be educated on utilizing sustainable development within the bounds of the market. If it sounds like colonialism that is because it is.

For example, there exists specific types of green grabs known as conservation enclosures where the market is seen as the best way to conserve biodiversity. Hence, authorities are privatizing, commercializing and commoditizing nature at an alarming rate through payment for ecosystem services to wildlife derivatives. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), a multilateral treaty set up at the 1992 UN Earth Summit has a target the protection of 17 percent of terrestrial and inland water and 10 percent of coastal and marine areas. For instance, Conservation International (CI) pushed the government of Madagascar to protect 10 percent of its territory, while in Mozambique a British company negotiated a lease with the government for 19 percent of the country’s land. President Elizabeth Sirleaf Johnson of Liberia called for the extradition of a British businessman accused of bribery over a $2.2 billion carbon offsetting deal. The deal was to lease one-fifth of Liberia’s forests, which account for 32 percent of its land. In Uganda, a Norwegian company leased land for a carbon sink project, which evicted 8,000 people in 13 villages.

In Oxfam Australia’s 2016 report on land grabs, palm oil has become “responsible for large-scale deforestation, extensive carbon emissions and the critical endangerment of species… India, China and the European Union (EU) are the largest consumers of palm oil globally.” The European Union’s renewable energy policy being a significant driver of global palm oil demand due to its aim to source 10 percent of transport energy from renewable sources by 2020, which has increased its palm oil usage by 365 percent.

Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) is an effort to create a financial value for the carbon that is stored in forests. It is used to justify green grabbing and is expected to be one of the biggest land grabs in history. By using REDD+ as a conservation mechanism and a financial stream, “the CDB is both legitimating the commodity of carbon itself and helping to create the market for its trade.” The CDB is forming new nature markets along with new nature derivatives whereby investors speculate on future values encompassed in, for instance, species extinction like that of tigers.

Financial Fragility

Hyman Minsky was fully aware that a capitalist system was a monetary system with financial institutions that were prone to instability. Minsky is famous for saying that the strength of capitalism is that it comes in at least 57 varieties. The last and current stage is Money Manager Capitalism, which was made up off highly levered profit- seeking organizations like that of money market mutual funds, mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds, and private pension funds. The financial instability hypothesis argues that the internal dynamics of capitalist economies over time give rise to financial structures, which are prone to debt deflations, the collapse of asset values, and deep depressions. Minsky has always warned, “Stability is Destabilizing.”

Money managers act as agents. They pursue short-term profits by trading instruments that are not easily verifiable, which makes fraud likely possible in carbon markets. The dramatic rise in securitization has opened up national boundaries leading to the internationalization of finance. Securitization within the carbon markets increases the risk of leading to boom-bust cycles. At present, speculators are the major players in carbon trading and their dominance in carbon markets is growing at an alarming rate. Financialization is an important precondition for the rise and operation of carbon offsets. The financial innovation in this scheme is that it uses nature itself as a financial instrument. Moreover, it is selling nature to save it and then saving nature to trade it.

‘Green bonds’ are carbon assets that are sold to the Northern hemisphere, backed by Southern land and Southern public funds. Lohmann shares that financial speculation of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) are at least based on specifiable mortgages on actual houses while climate commodity or subprime carbon cannot be specified, quantified, or verified even in principle. Even conservatives and Republicans have said, “if you like credit default swaps, you’re going to love carbon derivatives.” It has become apparent that carbon markets are not only driven by trade, but also by speculation. Carbon derivatives are growing at a fast rate as speculators are moving from other assets towards carbon. Whereas once investors bet on the collapse of the US housing market, there are some traders who are betting on the collapse of the carbon credit market.

As more investors, specifically hedge funds, enter the carbon markets, they increase market volatility and create an asset bubble or ‘carbon bubble’. Money managers by acting as agents trade carbons and increase financial fragility. Their income is driven by assets under management and short-term rates of return. Hence if they miss the benchmark, they will lose their clients. So they act on short profit bases by taking risky positions, and carbon trading provides those risks. In brief, using Minsky’s theory, we can predict with confidence that the carbon market is inherently unstable and that in addition to its not achieving its goal of reducing emissions, it is also heading to a financial disaster.

Even though Minsky pushed for regulation when it came to financial markets, regulating carbon markets will not solve the problem. Tighter regulation of carbon markets, particularly secondary and derivative markets is just a Band-Aid solution and will fail to affect fundamental change. Financial markets have had to be bailed out again and again. However, as a British Climate Camp activist said “nature doesn’t do bailouts.” On a global scale, GHG emissions have gone up. There is an offshoring of emissions. The best policy would be eliminating offsets, specifically from the developing world. Furthermore, there needs to be policies that encourage low-carbon technology as used in Sweden. Another policy recommendations would be a harmonized carbon tax.

Written by Mariamawit F. Tadesse

Illustrations by Heske van Doornen