It’s conventional wisdom among pundits that automation will cause mass unemployment in the near future, fundamentally changing work and the social relations that underpin it. Part 1 of this series contrasted this extreme rhetoric with the data that should support the inevitable robot apocalypse, and found that these predictions are likely motivated by politics or outlandish assessments of technology, not data. Part 2 assesses the technology behind these predictions, and follows a thread from the mid-20th century onwards. Subsequent parts will examine the political economy of automation in both general and specific ways, and will also discuss what the future should look like — with or without the robots.

The Automation Grift: From Flying Cars to Ordering Cat Food

on the Internet – Part 2

By Kevin Cashman

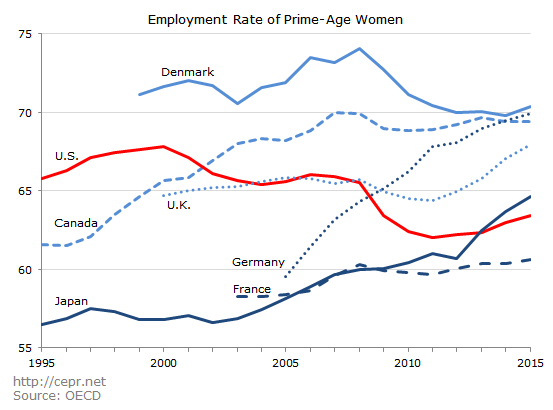

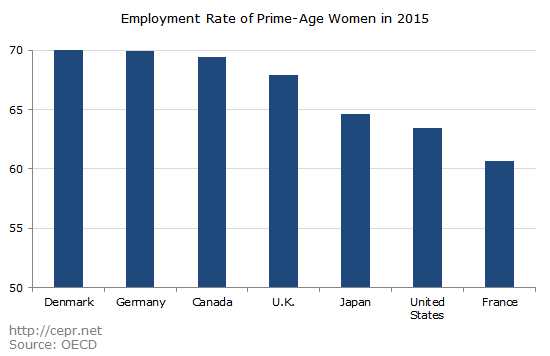

Part 1 of this article made a case that macroeconomic data does not suggest that there is rapid automation occurring broadly in the economy nor in large industries or sectors. Other indicators, like slack in the labor market, support that assertion. It pointed to periods of rapid automation in the past as well, and found these were times with generally low unemployment and healthy job growth.

Regardless of the data past or present, there are still claims that society is on a precipice, facing mass unemployment due to wide-scale automation. Many say that the technology in the near future is different than developments that occurred in the past, and that instead of slow or moderate change that the economy can adapt to, the rate of change will be so profound that suddenly millions will be out-of-work.

There are good reasons to be suspicious of this narrative. First, it is very difficult to predict how technology will develop and affect the world, and if it will be viable or even necessary in the first place. Second, adopting new technology — for example, automating a process and replacing workers — and more importantly, the threat of adopting new technology, gives power to employers and capital instead of workers. This weaponization of technology needs to be credible in order to be taken seriously; hence, it relies on the broader narrative that rapid automation is happening. The first point will be considered now; the second, in Part 3.

The (False) Promises of Technology

Predicting how technology affect the future is a difficult endeavor. The flying cars, spaceships, and moon bases that many were sure would arrive by the year 2000 never materialized. Anthropologist David Graeber posits that technological progress did not keep up with imaginations because capitalism “systematically prioritize[s] political imperatives over economic ones.” In a capitalist system like that in the U.S., if political threats do not align with technological advancement like they did during part of the Cold War, flying cars will stay in science fiction books, he says. As the perceived threat from the Soviet Union fell away, neoliberalism’s project shifted to cementing itself as the only viable political system, at the “end of history.”

More recent predictions have remained as bold as they were in the past, but reflect this change in focus. Audrey Watters, an education technology writer, details many in her excellent presentation, “The Best Way to Predict the Future is to Issue a Press Release.” She makes the case that narratives are spun about technology for mostly political reasons or for self-interest, rather than around higher, collective ideals. Bold predictions today are about the destruction and privatization of educational institutions, technology as consumption, or mass unemployment as human labor fades into obsolescence. Pointing to the dismal track record of those who analyze technological trends — based on methods that include opaque and ill-suited taxonomies and graphs, like the one-way hype cycle — she suggests that we are actually in a period of technological stagnation. “[T]he best way to resist this future,” she says, “is to recognize that, once you poke at the methodology and the ideology that underpins it, a press release is all that it is.”

Recent evidence from the dot-com bubble lends itself to these observations. Over-enthusiastic predictions of how the Internet would fundamentally change nature of shopping — not quite a lofty aspiration to begin with — led in large part to the bubble, which popped when it became clear that these companies’ business models did not work. (For example, individually shipping very heavy bags of pet food is expensive, a fact lost on the “innovative” owners of, and “savvy” investors in, Pets.com.) As neoliberalism was busy fashioning itself as the only ideology left standing, it served as the basis for allocating capital in unproductive ways. Whereas the ballooning of the finance sector over the last forty years is sustainable inasmuch as bankers are able to make money by creating and protecting the illusion of their usefulness, the dot-com era was a hard landing for companies that tried the same approach but ultimately could not drum up enough business to survive.

But even if past predictions are incorrect and past technological advances were limited (or had an economic potential that was much less than anticipated), the technology that is developing today could still could be extraordinary and kick off a period of very rapid automation, right? Before going further it is important to define what sort of technological developments could lead to these sorts of changes in the labor market. Often general advances in technology, or things like Moore’s law or speculation about the singularity, are used as evidence that the conditions that underlie the economy are shifting today. Here it is worth quoting directly from Economic Policy Institute’s State of Working America:

“We are often told that the pace of change in the workplace is accelerating, and technological advances in communications, entertainment, Internet, and other technologies are widely visible. Thus it is not surprising that many people believe that technology is transforming the wage structure. But technological advances in consumer products do not in and of themselves change labor market outcomes. Rather, changes in the way goods and services are produced influence relative demand for different types of workers, and it is this that affects wage trends. Since many high-tech products are made with low-tech methods, there is no close correspondence between advanced consumer products and an increased need for skilled workers. Similarly, ordering a book online rather than at a bookstore may change the type of jobs in an industry — we might have fewer retail workers in bookselling and more truckers and warehouse workers — but it does not necessarily change the skill mix.”

The takeaway from this should be that some technological advances that seem significant are not necessarily things that threaten jobs, change their pay or working conditions, or point to a jobless future. Technology can create new consumer products — let’s say smartphones — that seem like they fundamentally change the foundation of the economy. But they actually only shift jobs to the companies making smartphones, and don’t mean that workers making consumer products are somehow unnecessary. More significant developments like the technology behind the car or airplane can make entire industries obsolete but also can create an entire ecosystem of industries that generate wealth. Still other advancements can reduce the costs of products to a large degree so that they are increasingly used as inputs in other industries, benefiting both supplier and buyer.

These sorts of technological development are usually conflated with each other, and with the kind that is supposed to lead to mass automation and job loss. That kind of development is when very expensive robots or software replace humans completely, without spawning new industries and jobs. Two commonly cited examples are self-driving cars and delivery services. Delivery robots and drones might capture imaginations (and make for good PR) but that doesn’t mean that the economics behind them lead to a situation where workers will be replaced anytime soon. Self-driving car technology is massively hyped, but many think they won’t arrive in even a lifetime. Labor platforms, like TaskRabbit, a marketplace to find help with errands or odd jobs, or Uber, the taxi app, are other Silicon Valley “innovations” often lumped in with this discussion. But they don’t threaten to reduce the total number of jobs at all: they shift jobs to their platforms.

This doesn’t mean that more original uses for technology couldn’t significant impact specific sectors. However, it’s likely that, in general, technology that does affect jobs will complement those positions, replacing or changing the specific tasks that workers do, but not going as far as replacing them in all cases. For jobs that are replaced wholesale, it shouldn’t be assumed that they will disappear overnight. There still need to be decisions, investment, and planning involved in replacing workers with (usually expensive) alternatives, which are all things that take time. This has certainly been the case in manufacturing. One interesting table from the Bureau of Labor Statistics that supports this point details the fastest declining occupations. Even extrapolating out ten years, the BLS assumes that there will be significant employment in these occupations. And any changes will vary by specific industry and occupation. Even then, many “low-skill” or low-paying jobs, especially in the service sector, are not conducive to automation very much at all. (And the robots must have forgotten that those were their targets, since many of the fastest growing jobs require no formal education or only a high school degree.)

There’s really no definitive way to tell either way if the robot apocalypse is upon us. But the precedence for wildly inaccurate predictions; the history of technology companies being unable to deliver on extravagant promises; the fact that the technology that would threaten jobs today is more suited toward slow, incremental changes like in the past; and that the orientation of our political system is toward prioritizing political, rather than economic imperatives, strongly suggests that the robots are probably much farther off than is conventionally accepted.

Is the recent deluge of talk of disruptive technological change, ubiquitous automation, and mass unemployment a continuation of the trends and mistakes that Graeber and Watters have highlighted? It seems so, and might even be approaching the lunacy of the dot-com era. Venture capitalists pour billions of dollars into unprofitable companies with questionable business models, which are in turn valued at billions of dollars. Many of the most popular and “innovative” businesses are simply delivery services, transportation companies, or in the consumer goods industry. How many different delivery services does society need? How many different taxi apps does it need? Does anyone really need a $700 juicer, especially if it isn’t even necessary? How are these ways of doing business adding value to the economy, let alone the beginning of a jobless future? More ambitious technology has proven to been a bust, especially in biotechnology. One also has to question the value of recent technological assessments and predictions when many of the economic and political commentators that are doing that prognosticating couldn’t see the dot-com bubble or even the massive housing bubble that preceded the Great Recession.

The reality is that companies that are seen as the forebearers of mass automation are often unoriginal, repackaging old ideas and existing technology and using political power, venture capital money, and a lot of press releases to survive. Like Graeber said, these “innovations” seem to be more in line with boosting the prevailing economic and political ideology. Old, obsolete ideas like flying cars have been resurrected; for example, as part of a public relations and investment strategy to distract from Uber’s myriad scandals and disastrous finances.

If anything, the novelty of this new era of technology seems to come from the lessons business have learned from the survivors of the dot-com bubble, like eBay, Google, and Amazon: mainly, that business models don’t need to make sense as long as a company is able to take over a big slice of the market and change the terms of that market. In this way, vague ideas about technology and the usefulness of Silicon Valley — promoted by neoliberal icons like Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg — are used as a smokescreen for anti-competitive and anti-worker practices that seek to change the economic landscape.

Part 3 will explore an underexamined consequence of this debate: how it affects the social relations between employers, workers, and the government that are a foundation of the economy.

About the Author

Kevin Cashman lives in Washington, DC, and researches issues related to domestic and international policy at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Follow him on Twitter: @kevinmcashman.