Sectoral analysis provides a key framework for understanding the macroeconomy. GDP is a flow representing the value of all goods and services produced in a specific time period. This flow can be tracked in two different ways, on the spending side and on the income side. On the spending side the GDP components are: consumption (C), investment (I), government spending (G), and the difference between exports (X) and imports (M)–or just net exports (X-M). On the other hand, the income that makes up GDP, is consumption (C), savings (S), and taxation (T). These two ways of measuring GDP are two sides of the same coin, a product of double-entry accounting, and must always be equal.

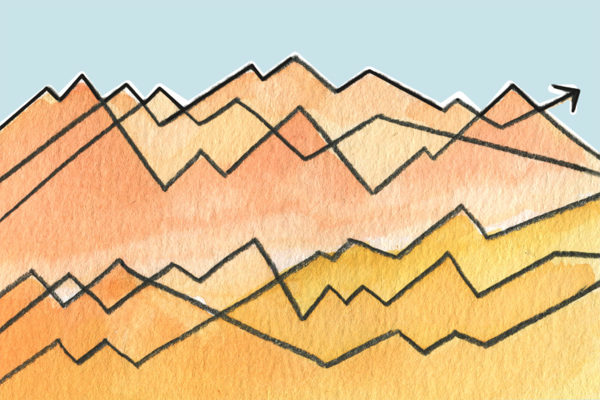

Thus sectoral analysis comes from equating and simplifying the spending and income views on GDP. You can follow the math on the wikipedia page here, but after equating these two different views and simplifying we end up with the equation (S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M). These are our three sectors of analysis. The private sector surplus/deficit is defined by the difference between savings and investment (S – I). The government surplus/deficit is its spending minus the amount it takes back in taxes (G – T). And finally, the foreign sector surplus/deficit is the amount of exports by the country less the amount it imports (X-M). We can see this identity visually in the following graph. You can hover your mouse over specific bars to see specific values and dates.

The graph setup this way shows how government fiscal deficits (orange bars) make their way towards the rest of the world or into the private sector. Why have we had a persistent current account deficit (green bars) since at least 2000? Well, the rest of the world wants US dollars. We want to import their goods and services. Since the US is a net importer of goods and services, we are a net exporter of US dollars. Thus some of the deficit each quarter makes its way out of the country. The rest of the deficit makes its way into the domestic private sector (blue bars). The private sector is composed of households and businesses. The great recession was caused due to poor household balance sheets, among other things. If you were following the sectoral balances graph closely in 2000-2008, you could see how the private sector was continuously indebted, both households and businesses. This was unsustainable.

The government deficit expanded post recession due to automatic stabilizers, repairing poor household balance sheets. This muddling on continues today. The past few years have seen domestic business go into debt, although the last two quarters have shown a slight surplus. Households and institutions have maintained a surplus since 2008. From a purely sectoral balances perspective, as long as we maintain our government deficit and the rest of the world continues to want US goods and services, the US private sector seems poised to continue muddling along. Splitting households into top 10% and bottom 90% would be an interesting exercise to see how these modest surpluses have been distributed. I will keep an updated quarterly graph here on The Minsky’s as FRED releases data. I hope you found these graphs useful and insightful.