Back in 2002, economists Shane Frederick, George Lowenstein, and Ted O’Donoghue found that people generally value the present over the future—something they called a time preference. While this seemed intuitive for most people, economists Marcus Dittrich and Kristina Leipold later showed that this time preference is not necessarily uniform across gender lines. Following an online experiment with 1019 subjects, they found that men were more impatient than women, choosing to receive rewards immediately, while “women are better able than men to delay gratification and tend to be more self-disciplined.” In a county like the United States—which is mostly controlled by men—it is not surprising that policymakers have continually privileged the present over the future.

Despite the fact that 97 percent of all climate scientists believe that climate change is real, many Republican leaders (Donald Trump, for instance) still argue it is some fictional conspiracy, while many others who do recognize the reality of climate change, still privilege economic growth over environmental protection. There is a deeply embedded culture of masculinity in the United States that is problematic for those who want to create constructive solutions for mitigating climate change. Researchers Aaron R. Brough, James E.B. Wilkie, and their colleagues conducted a series of experiments with over 2,000 participants and found a “psychological link between eco-friendliness and perceptions of femininity” and that “men may shun eco-friendly behavior because of what it conveys about their masculinity.”

Perhaps what is needed is a more feminist approach to climate change. As journalist Maria Laurino writes, “Contemporary American feminism has primarily come to mean championing women’s autonomy and challenging the privileging of male over female.” In other words, it means that feminists do not privilege men over women—who are equal in every capacity and therefore should have equal opportunity. If you are a man, being a feminist does not mean you are somehow feminine or unmanly, it simply means that you don’t believe that men are somehow exceptional and that women are equally competent to take leadership positions.

Do more women in leadership roles translate into more environmental protection? Sociologists Kari Norgaard and Richard York surveyed women policymakers in 19 countries that hold 92 percent of the world’s population and found that “nations with higher proportions of women in Parliament are more prone to ratify environmental treaties than are other nations.” If women are more likely than men to delay gratification, pursue environmental protection, and cooperate internationally, doesn’t it make sense that they should have greater authority over environmental research and policy?

What about those who guide policymakers, such as economists? Researchers Ann Mari May, Mary McGarvey, and David Kucera surveyed economists in universities across 18 nations in the European Union and found that male economists not only prefer market solutions over government intervention, they are more skeptical of environmental protection than women economists. Isn’t economics supposed to be an objective science? As economist Duncan Foley wrote in 2016, economics is not an objective science because it is guided by values — which determines which research questions to pursue and which kinds of economic policies economist will support and legitimize.

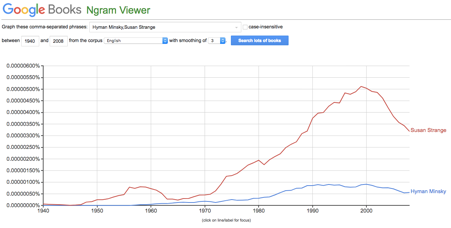

In addition, May, McGarvey, and Kucera also found that male economists were two times more likely to become full professors. “Despite an increase in the number of women entering economics from the 1970s to the 1990s,” the researchers wrote, “the profession remains predominantly male.” Even the former chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, acknowledged that the field of economics favors men over women. Despite the evidence that suggest the economics profession discriminates against women, Ben Casselman and Jim Tankersley of the New York Times, report that some male economists dismiss the notion of a gender bias, “arguing [instead] that gender disparities must reflect differences in preference or ability.” As this article has shown, this is clearly not the case.

Given the data that suggests that female economists and policymakers are more open to responding to environmental issues (see also here, here, and here), it seems pretty clear that we need a more feminist approach to alleviating climate change. A greater representation of women in senior economics positions, as researchers May, McGarvey, and Kucera show, would lead to a more diverse set research questions — widening the range of discussion about climate change and creating a more diverse set of conclusions and policy outcomes.

About the Author: Johnny Fulfer received a B.S. in Economics and a B.S. in History from Eastern Oregon University. He is currently pursuing an M.A. in History at the University of South Florida and has an interest in political economy, the history of economic thought, intellectual and cultural history, and the history of the human sciences and their relation to the power in society.