“Don’t be seduced into thinking that that which does not make a profit is without value.”

Arthur Miller

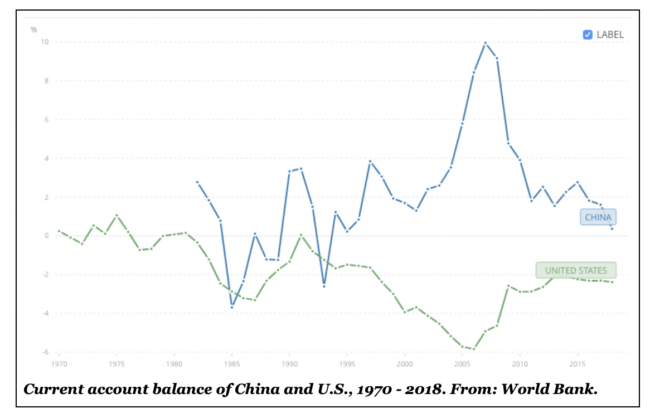

The recent development in the payments industry, namely the rise of Fintech companies, has created an opportunity to revisit the economics of payment system and the puzzling nature of profit in this industry. Major banks, credit card companies, and financial institutions have long controlled payments, but their dominance looks increasingly shaky. The latest merger amongst Tech companies, for instance, came in the first week of February 2020, when Worldline agreed to buy Ingenico for $7.8bn, forming the largest European payments company in a sector dominated by US-based giants. While these events are shaping the future of money and the payment system, we still do not have a full understanding of a puzzle at the center of the payment system. The issue is that the source of profit is very limited in the payment system as the spread that the providers charge is literally equal to zero. This fixed price, called par, is the price of converting bank deposits to currency. The continuity of the payment system, nevertheless, fully depends on the ability of these firms to keep this parity condition. Demystifying this paradox is key to understanding the future of the payments system that is ruled by non-banks. The issue is that unlike banks, who earn profit by supplying liquidity and the payment system together, non-banks’ profitability from facilitating payments mostly depends on their size and market power. In other words, non-bank institutions can relish higher profits only if they can process lots of payments. The idea is that consolidations increase profitability by reducing high fixed costs- the required technology investments- and freeing-up financial resources. These funds can then be reinvested in better technology to extend their advantage over smaller rivals. This strategy might be unsustainable when the economy is slowing down and there are fewer transactions. In these circumstances, keeping the par fixed becomes an art rather than a technicality. Banks have been successful in providing payment systems during the financial crisis since they offer other profitable financial services that keep them in business. In addition, they explicitly receive central banks’ liquidity backstop.

Traditionally, the banking system provides payment services by being prepared to trade currency for deposits and vice versa, at a fixed price par. However, when we try to understand the economics of banks’ function as providers of payment systems, we quickly face a puzzle. The question is how banks manage to make markets in currency and deposits at a fixed price and a zero spread. In other words, what incentivizes banks to provide this crucial service. Typically, what enables the banks to offer payment systems, despite its negligible earnings, is their complementary and profitable role of being dealers in liquidity. Banks are in additional business, the business of bearing liquidity risk by issuing demand liabilities and investing the funds at term, and this business is highly profitable. They cannot change the price of deposits in terms of currency. Still, they can expand and contract the number of deposits because deposits are their own liability, and they can expand and contract the quantity of currency because of their access to the discount window at the Fed.

This two-tier monetary system, with the central bank serving as the banker to commercial banks, is the essence of the account-based payment system and creates flexibility for the banks. This flexibility enables banks to provide payment systems despite the fact the price is fixed, and their profit from this function is negligible. It also differentiates banks, who are dealers in the money market, from other kinds of dealers such as security dealers. Security dealers’ ability to establish very long positions in securities and cash is limited due to their restricted access to funding liquidity. The profit that these dealers earn comes from setting an asking price that is higher than the bid price. This profit is called inside spread. Banks, on the other hand, make an inside spread that is equal to zero when providing payment since currency and deposits trade at par. However, they are not constrained by the number of deposits or currency they can create. In other words, although they have less flexibility in price, they have more flexibility in quantity. This flexibility comes from banks’ direct access to the central banks’ liquidity facilities. Their exclusive access to the central banks’ liquidity facilities also ensures the finality of payments, where payment is deemed to be final and irrevocable so that individuals and businesses can make payments in full confidence.

The Fintech revolution that is changing the payment ecosystem is making it evident that the next generation payment methods are to bypass banks and credit cards. The most recent trend in the payment system that is generating a change in the market structure is the mergers and acquisitions of the non-bank companies with strengths in different parts of the payments value chain. Despite these developments, we still do not have a clear picture of how these non-banks tech companies who are shaping the future of money can deal with a mystery at the heart of the monetary system; The issue that the source of profit is very limited in the payment system as the spread that the providers charge is literally equal to zero. The continuity of the payment system, on the other hand, fully depends on the ability of these firms to keep this parity condition. This paradox reflects the hybrid nature of the payment system that is masked by a fixed price called par. This hybridity is between account-based money (bank deposits) and currency (central bank reserve).

Elham Saeidinezhad is lecturer in Economics at UCLA. Before joining the Economics Department at UCLA, she was a research economist in International Finance and Macroeconomics research group at Milken Institute, Santa Monica, where she investigated the post-crisis structural changes in the capital market as a result of macroprudential regulations. Before that, she was a postdoctoral fellow at INET, working closely with Prof. Perry Mehrling and studying his “Money View”. Elham obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Sheffield, UK, in empirical Macroeconomics in 2013. You may contact Elham via the Young Scholars Directory