In one of Donald Trump’s rants, he claimed the reason why there are so many German cars in the U.S. is that their automakers do not behave fairly. The German economy’s prompt response was that “the U.S. just needs to build better cars.” However, this time, probably without even realizing it, Donald Trump was on to something – Germany’s currency setup does give it unfair trade advantages.

While China is commonly accused of currency manipulation to provide cheap exports, the IMF has recently decided the renminbi (RMB) is no longer undervalued and added it in its reserve currency basket, along with other major currencies. However, an IMF analysis of Germany’s currency found “an undervaluation of 5-15 percent” for the Euro in the case of Germany. Thus for Germany, the Euro has a significantly lower value than a solely German currency would have.

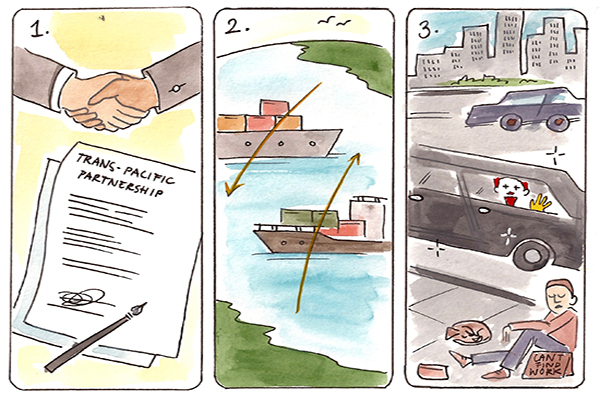

Since the Euro was introduced, Germany has become an export powerhouse. This is not because after 2000 the quality of German goods has improved, but rather because as a member of the Eurozone, Germany had the opportunity to boost its exports with policies that allowed it to maintain an undervalued currency.

Germany and France are the largest Eurozone economies. Prior to joining the Eurozone, both countries had modest trade surpluses.

In the above figure we can see how following the implementation of the Euro, the trade balances of Germany and France completely diverged. The French moved to having a persistent trade deficit (importing more than they export), while Germany’s surplus exploded (exporting much more than they import). After a brief decline in the surplus in the immediate aftermath of the crisis, it is now again on the rise.

In the early 2000s Germany undertook several national policies to artificially hold wages down. These measures were seen as a success for Germany globally. By being part of the Eurozone and holding down wages, the Germans could export at extremely competitive prices globally. Had they not been part of the Eurozone, their currency would have appreciated, and they would not have the same advantages.

In the aftermath of the European debt crisis, Germany took a tough stance on struggling debtor countries. Under German leadership, the European Commission imposed draconic austerity measures on countries such as Greece to punish them for spending irresponsibly. Spearheaded by Germany, The EU (along with the IMF) offered a bailout to Greece so that it could pay the German and French banks it owed money to.

This bailout came with strict conditions for the Greek government that was forced to impose harsh austerity. The promise was that if the government cut its spending, the increased market confidence would help the economy recover. As a member of the Eurozone, Greece had very limited monetary policy tools it could use. Currency devaluation was no longer an option, the country was stuck with a currency that was too strong for its economy.

Meanwhile Germany prospered and enjoyed the perks of an undervalued currency. Being able to supply German goods at relatively low prices, Germany’s exports flourished. At the same time, Greeks, and other countries at the periphery of the union, were only left with the choice to face a strong internal devaluation, which meant letting unemployment explode and wages collapse until they become attractive destinations for investment.

Germany consistently broke the rules of the currency area, without ever being punished. When it first broke the deficit limits agreed upon by Eurozone members in 2003, the European Commission turned a blind eye. Germany is often considered to have set an example for other EU nations by practicing sound finance, and having a growing, healthy economy.

Greece, on the other hand is blamed for spending too much on social services, and many of its problems are blamed on being a welfare state. When you compare the actual numbers, however, Greece’s average social spending is much less than that of Germany. Between 1998 and 2005, Greece spent an average of 19 percent of GDP, while Germany spent as much as 26 percent.

To address these vast differences in the trade patterns of the EU nations, the European Commission introduced the so-called “six-pack” in 2011. These regulations introduced procedures to address “Macroeconomic Imbalances.” However, as found in the Commission’s country report “Germany has made limited progress in addressing the 2014 country-specific recommendations.”

Germany’s trade competitiveness comes at the price of making other members of the Eurozone less competitive. This is something that Germany needs to be aware of when responding to the problems other economies are facing. Currently Germany is demanding punishments for countries whose have few policy tools available to stimulate growth as Eurozone members.

However, Germany should keep in mind that the Euro is preventing the currency adjustments that would take away its trade competitiveness. Without a struggling EU periphery, there wouldn’t be a flourishing Germany.

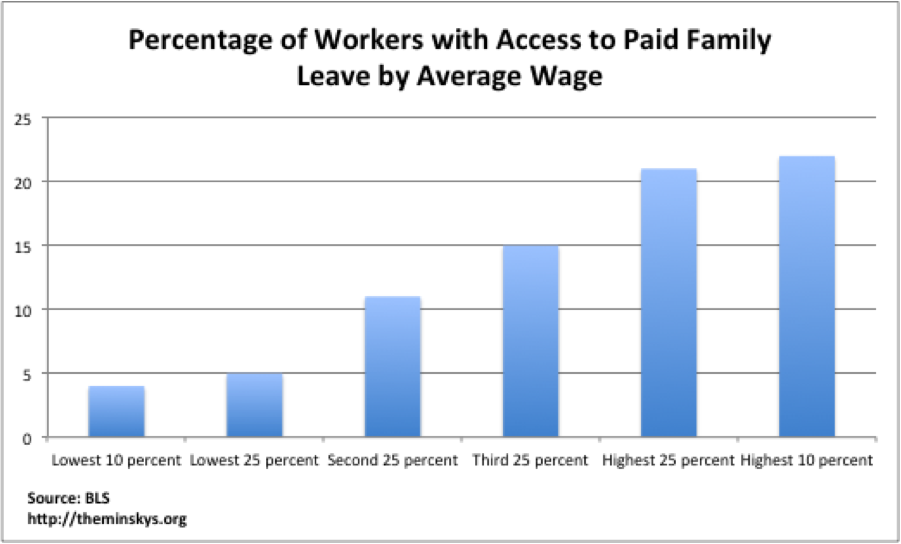

months for a company that hires at least 50 people. While this might be a start, it leaves about half of the workers uncovered. Even for those who are covered by the FMLA, they must afford giving up their paychecks for those 12 weeks. The act does little to help those who are left out or cannot afford to renounce their paychecks. This adds pressure on people at the lower end of the income distribution that might be pushed below the poverty line if forced to give up their incomes.

months for a company that hires at least 50 people. While this might be a start, it leaves about half of the workers uncovered. Even for those who are covered by the FMLA, they must afford giving up their paychecks for those 12 weeks. The act does little to help those who are left out or cannot afford to renounce their paychecks. This adds pressure on people at the lower end of the income distribution that might be pushed below the poverty line if forced to give up their incomes. introducing the policy had a positive or no noticeable effect on 89 percent of the businesses surveyed. However, these policies are very modest compared to the rest of the

introducing the policy had a positive or no noticeable effect on 89 percent of the businesses surveyed. However, these policies are very modest compared to the rest of the

disproportionately affects lower-income families is the cost of childcare. The Economic Policy Institute

disproportionately affects lower-income families is the cost of childcare. The Economic Policy Institute  With childcare costs

With childcare costs