Embracing industrial policy and economic planning is essential to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and environmental damage.

By Kevin Cashman

One of Margaret Thatcher’s often-used slogans was TINA, or “there is no alternative.” There is no alternative, she meant, to the neoliberalism that became dominant in the 1970s and 1980s. After a coup led to the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991, this idea led to even more smug declarations of victory for the neoliberal order as well as the popularization of Francis Fukuyama’s articulation of the “end of history.”

With the countless failures of neoliberalism coming into focus for all sides of the political spectrum — one of those failures being climate change, which is already leading to potentially irreversible changes in ecological systems — it is worth considering different approaches to economics that could start to address these problems. These include some concepts, like industrial policy and economic planning, which have been summarily dismissed by powerful people in both major parties in the United States. In the context of a Green New Deal, these ideas provide valuable insights on what successful policy and outcomes would look like.

Industrial policy and economic planning

Industrial policy and economic planning and management are vital to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Briefly, industrial policy is often thought of as policies that strategically supports certain industries, while economic planning involves government intervention in markets to various degrees. (Industrial policy is a type of economic planning.) Over the past 40 years, both concepts have been much maligned by Democrats and Republicans. Industrial policy is attacked as protectionism which spoils “free” trade, and economic planning is often tied to socialist and communist political and economic systems (and thus assumed to be implicitly harmful). Industrial policy is also often tied to economic planning as a way to discredit it.

The dirty secret in development is that the countries that have been most successful at raising living standards and growing their economies engage in planning that is outside what the neoliberal order considers acceptable. These include the Soviet Union, which oversaw vast improvements in living standards and transformed the country into a superpower, and China, which not only has the largest economy in the world today but has reduced poverty to a degree that can only be regarded as one of humanity’s most impressive achievements. The Soviet Union and China didn’t and don’t pretend to be guided by neoliberalism, but other countries, such as Japan and South Korea do. Their development was also characterized by industrial policy, “protectionism,” and currency management. Historically, countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, some of the most enthusiastic promoters of neoliberalism, are guilty of this as well. Simply put, government intervention in markets and industry is how the government can move the economy to solve large problems, like poverty, underdevelopment, and hopefully in the future, climate change.

Planning for the benefit of the rich

If these policies are so beneficial, why does neoliberalism eschew them? While this is perhaps an oversimplification, it’s because the interests that promote neoliberalism risk losing power and money from their adoption. The hollowing out of social welfare programs and the introduction of markets into various facets of life have led to the accrual of wealth and power for some, and those people, who might have been already rich or powerful to begin with, don’t want to lose those benefits. Neoliberalism also has different apparatuses that support it in academia, media, the state, and other institutions that give backing to its ideas. As an example, free trade in a vacuum might make sense, but “free” trade structured to benefit the rich does not. However, said apparatuses will continue to push the narrative that “free” trade is inevitable and unavoidable. Likewise, austerity — the idea the government should close budget deficits and reduce its debt — does not improve economies and makes very little sense, but it was the default policy prescription during the worst recession in 80 years, and it destroyed many lives.

That leads to another point: the United States and other countries committed to capitalism and neoliberalism actually practice industrial policy by enacting policies that largely benefit the rich. This protectionism can be found in many different parts of the economy. The supply of doctors, dentists, and lawyers is artificially restricted (thus raising wages), the Export–Import Bank subsidized large companies that had no need for subsidies, intellectual property rules allow rents to be extracted on drugs or software much longer than is necessary, the gains from government research and development are privatized, and the financial sector is largely waste — just to name a few examples.

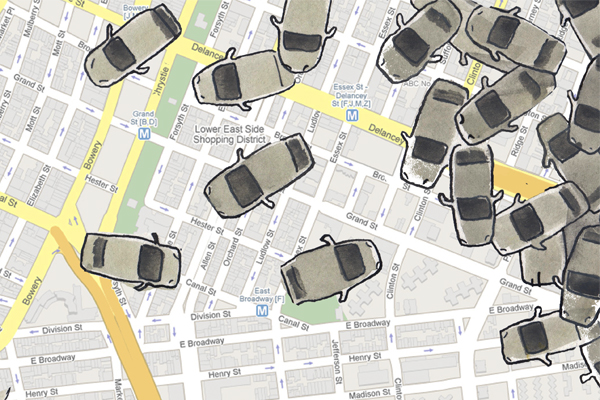

Transportation and urbanism as examples of poor planning

Since economic planning in the United States is focused largely on extracting gains for the rich, it also means that there is inadequate planning around pressing problems, like climate change. The transportation sector illustrates these inefficiencies and coordination failures well.

The transportation sector is the largest or second-largest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Overwhelmingly, light-duty vehicles are responsible for most of these emissions — 60 percent — while Medium- and Heavy-Duty Trucks are 23 percent. Aircraft (9 percent), Rail (2 percent), Ships and Boats (2 percent), and everything else (4 percent) make up the rest.

In many cities in the United States, vehicles are the most common way to commute to work or get around. This is in large part due to poor and disjointed transportation policy and is also why light-duty vehicles contribute so much to emissions. Medium- and heavy-duty truck emissions are high as well (and rail, low) because trucks are the predominant way goods are transported across the country and within cities. A sensible climate policy to address this would 1) limit the emissions from vehicles and 2) shift to better ways of transporting people and goods.

Over the last thirty years, the United States has largely failed at both of these goals. Vehicle fuel efficiency has increased modestly via standards (after efficiency decreased in the 1990s), although these are undermined by states in various ways. Gasoline is by far the most common fuel, despite the availability of technology that could have supplanted it. Electric vehicles and gasoline/electric hybrid vehicles were developed and viable in the 1990s, but absent incentives to produce them or require their adoption were not produced in large numbers. Electric vehicles were clearly superior in terms of their environmental impact because they relied on electricity generation, which could be from clean sources. Instead, the United States spent significant time and money developing hydrogen, ethanol, and compressed natural gas vehicles, which had significant disadvantages (ethanol subsidies also had significant harmful effects abroad, raising the prices of food in poor countries, some of which had been encouraged to adopt trade policies that exposed themselves to this danger). This mirrors the United States’ slow recognition that wind and solar power represented the future of electricity generation, which was in part due to the promotion of natural gas as supposedly a “transition fuel” and coal as “clean.”

The United States also has questionable priorities when organizing how people get around. Cities rely on car use to an unacceptable degree, which imposes large environmental and social costs. In Ivan Illich’s Energy and Equity, Illich argues that structures like the transportation system in the United States replicate class divisions and also reproduce and justify themselves without concern for whether they make sense at all. In this, he calculates that the “true” speed of a car, taking into account all of the costs, is 3.7 miles per hour. This serves more as a thought experiment than a calculation to rely on but makes his point. Given these costs, cities should focus on the ways of getting around that have the least social costs, like walking, cycling, and public transportation, as well as designing cities better in the first place so that the average person does not need to rely on cars to get around. Instead, cities are mostly doing the opposite: expanding car use, defunding public transportation, building boondoggles like Elon Musk’s under-city single-serve tunnels, expanding in irresponsible ways, relying on ride-hailing services, and indulging in poorly thought out services like dockless bikes and scooters. In this sense, venture capital is subsidizing modes of transportation that have high social and environmental costs, with the government’s backing. The promise of self-driving cars is also influencing the government’s actions. Self-driving cars, although useful in some respects, will exacerbate environmental and social problems in cities, and should represent only a small slice of how people travel in the future. Venture capital and Silicon Valley more broadly are changing how goods are transported as well. Deliveries, both within cities and between cities, are becoming more common. There are environmental costs to these distribution models, although there is scant acknowledgment of them. Packages sent from Amazon or a grocery delivery probably have more environmental costs than the equivalent trips to the store, for example.

A sensible way to limit emissions from transportation in the United States would be to rethink how cities develop and orient them around walking, cycling, and public transportation while restricting private car use. People should live close to where they work, cities should invest in free public transportation (especially buses, which are cheap and effective), and ban or discourage ride-hailing services or other in vogue technologies that have dubious environmental or social benefits. Electric cars should be rare but the norm and autonomous technology should be embraced (although their use should be also rare and used for the same special cases that normal car use would be used for, e.g. transporting the elderly). Rail should be expanded for both passenger and freight use. These are common sense and obvious solutions that the government should support.

China: an example for the world

The United States is the country most easily positioned to address climate change but it has done likely the least out of any rich country. China, a country significantly less wealthy than the United States, has likely done the most. In fact, a recent study provides some evidence that China’s carbon dioxide emissions peaked in 2013 and are declining in large part due to changes in China’s industrial structure, which includes pilot programs for pricing carbon, among many other things. China has:

- Drastically reduced its reliance on coal;

- Potentially reached peak emissions in a country that’s the world’s largest economy (but also significantly less developed than its peers);

- Become the largest buyer and producer of solar panels; leader in wind power installation and generation;

- Undertaken massive reforestation campaigns;

- A high adoption rate of electric cars.

China’s stunning progress has been called its own Green New Deal. The significance of a middle-income country enacting these policies to its short-term detriment should not be understated. Richer countries have struggled to meet modest emissions goals, and have also insisted that poorer countries undertake large reductions as a prerequisite for their own action. China nevertheless independently adopted policies that led to these achievements. In addition, it did this while continuing to pursue other goals, like poverty reduction.

How was China able to do this? China’s Communist Party undertook significant economic reforms in the 1980s and 1990s in order to grow China’s economy. These changes moved the country into a socialist market economy that introduces some elements of the market into the economy but that also gives the state significant control. The government owns significant parts of the economy and sectors deemed important. It also has more controls on private business than in the West — with agreement from those business leaders. These changes were seen as essential to China developing its productive capabilities and competing in the global economy under the current conditions but also as a step toward socialism and eventually communism.

Unlike in market socialism, economic planning is essential to China’s economy and occurs at many levels of the economy, including the top-most levels. Like other countries that have developed in the 20th century, this planning included export-oriented policies, technology transfers, support for specific industries, and management of its currency. In addition, part of the government’s planning includes the development of an internal market for China’s good and services. This planning, as well as other government policies, probably helped China avoid most of the harmful effects from the Great Recession. Indeed, China’s system seems to be able to largely avoid economic crises that are commonplace in the West, despite near-constant predictions of its economic collapse.

Integral to its more recent planning, is an emphasis on the ecological over the economic, which follows from Marx’s notion of metabolic rift and Soviet ideas about ecosocialism, that capitalism necessarily creates ecological crises and socialism must integrate the environment into the economy. Prioritizing ecological needs could lead to a slowing of the rate of exploitation of the earth’s resources, rather than just an avoidance of the most pressing ecological crisis. In China, this is the concept of an “ecological civilization,” which now has an underlying legal basis. While undoubtedly China believes that its focus on addressing environmental problems will help its long-term growth and stability, its understanding of the problems from a socialist perspective is important as well.

Despite these impressive achievements, China’s ability to set goals and achieve them has garnered little support or acknowledgment in the West. (In fact, poverty reductions from China are often misattributed to the “success” of capitalism elsewhere.) As the United States continues its slide from sole superpower to regional power, attacks on China have ramped up.

It is important to delineate the economic system in China with those of social democracies, like those in Europe. While some social democracies have had impressive achievements, their economic systems — based on exploitation historically and currently — do not fundamentally resolve the tension between classes nor give the government the power to act independently of the market to a large enough degree. Unsurprisingly, the social welfare aspects of these countries are under sustain attacks as politics have taken a turn to the right. As a different conception of neoliberalism, these countries nevertheless have austerity, anti-immigrant policies, and policies that encourage imperialism to various degrees.

Insights for climate action in the United States

China’s example provides general lessons for the United States. Capital does not naturally allocate itself to solutions that reduce environmental damage. Even if there were a price on carbon emissions, the government has tools that are needed to reach desired outcomes, which it also must set. The government also engages in research and development that would be unlikely to be conducted by the private sector, which is essential to taking action. These are examples of industrial policy and economic planning. Better management of the transportation sector, previously discussed, would have resulted in a large reduction of greenhouse gases, as would have management of other sectors of the economy. The government can also stop “wrong turns” before they happen, like the focus on developing hydrogen cars or technologies that have little practical or environmental benefits. The government should approach each sector of the economy with this mindset.

In order to use these economic approaches, international, national, and sub-national changes will need to be made. International financial institutions will need to abandon rules that limit industrial policy and economic planning, which have been baked into international financial systems. Given that the United States is probably the largest backer and enforcer of these rules, it would also have a lot of power to change them. Nationally, the United States needs to move past deficit politics and embrace the implications of Modern Monetary Theory, mainly, that taxes do not fund spending and that money is not a restraint on spending but inflation is. More simply put, the United States already has enough resources to enact ambitious policies, and taxes are a tool to keep people from getting too rich. Sub-nationally, the federal government would have to ensure that state and other jurisdictions would not undercut its policies. How cities are managed, in particular, needs to be rethought; the main economic engine of a metro area should control the policies of that area. More generally, the overarching drive toward growth, especially growth that does not take into account ecological damage, as opposed to specific policy outcomes, needs to be reevaluated.

Of course, the economic approaches discussed here and policies like the Green New Deal, in particular, will not be possible without political power. These approaches and policies are essential to taking effective action, however, so they should be integrated into the strategy to build that power as much as they should compose the solutions once that power is gained. Taking on neoliberalism is a daunting task, but it is necessary. It is a mistake to think that undertaking a transformation like that which is required to stop climate change will not require confronting capitalism, or the people who have obscured the ecological crises and contributed to it. China has already done much of the work necessary for creating an economic and political system that is able to make these changes, and there are many lessons to learn from it. Most importantly, is the realization that there is no alternative to increased management of the economy. The planet depends on it.