By Elham Saeidinezhad and Jack Krupinski

“As Stigum reminded us, the market for Eurodollar deposits follows the sun around the globe. Therefore, no one, including and especially the Fed, can hide from its rays.”

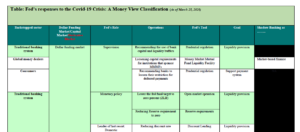

The COVID-19 crisis renewed the heated debate on whether the US dollar could lose its status as the world’s dominant currency. Still, in present conditions, without loss of generality, the world reserve currency is the dollar. The exorbitant privilege implies that the deficit agents globally need to acquire dollars. These players probably have a small reserve holding, usually in the form of US Treasury securities. Still, more generally, they will need to purchase dollars in a global foreign exchange (FX) markets to finance their dollar-denominated assets. One of the significant determinants of the dollar funding costs that these investors face is the cost of hedging foreign exchange risk. Traditionally, the market for the Eurodollar deposits has been the final destination for these non-US investors. However, after the great financial crisis, investors have turned to a particular, and important segment of the FX market, called the FX swap market, to raise dollar funding. This shift in the behavior of foreign investors might have repercussions for the rates in the US money market.

The point to emphasize is that the price of Eurodollar funding, used to discipline the behavior of the foreign deficit agents, can affect the US domestic money market. This usage of FX swap markets by foreign investors to overcome US dollar funding shortages could move short-term domestic rates from the Fed’s target range. Higher rates could impair liquidity in US money markets by increasing the financing cost for US investors. To maintain the FX swap rate at a desirable level, and keep the Fed Funds rate at a target range, the Fed might have to include FX derivatives in its asset purchasing programs.

The use of the FX swap market to raise dollar funding depends on the relative costs in the FX swap and the Eurodollar market. This relative cost is represented in the spread between the FX swap rate and LIBOR. The “FX swap-implied rate” or “FX swap rate” is the cost of raising foreign currency via the FX derivatives market. While the “FX swap rate” is the primary indicator that measures the cost of borrowing in the FX swap market, the “FX-hedged yield curve” represents that. The “FX-hedged yield curve” adjusts the yield curve to reflect the cost of financing for hedged international investors and represents the hedged return. On the other hand, LIBOR, or probably SOFR in the post-LIBOR era, is the cost of raising dollar directly from the market for Eurodollar deposits.

In tranquil times, arbitrage, and the corresponding Covered Interest Parity condition, implies that investors are indifferent in tapping either market to raise funding. On the contrary, during periods when the bank balance sheet capacity is scarce, the demand of investors shifts strongly toward a particular market as the spread between LIBOR and FX swap rate increases sharply. More specifically, when the FX swap rate for a given currency is less than the cost of raising dollar directly from the market for Eurodollar deposits, institutions will tend to borrow from the FX swap market rather than using the money market. Likewise, a higher FX swap rate would discourage the use of FX swaps in financing.

By focusing on the dollar funding, it is evident that the FX swap market is fundamentally a money market, not a capital market, for at least two reasons. First, the overwhelming majority of the market is short-term. Second, it determines the cost of Eurodollar funding, both directly and indirectly, by providing an alternative route of funding. It is no accident that since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, indicators of dollar funding costs in foreign exchange markets, including “FX swap-implied rate”, have risen sharply, approaching levels last seen during the great financial crisis. During crises, non-US banks usually finance their US dollar assets by tapping the FX swap market, where someone borrows dollars using FX derivatives by pledging another currency as collateral. In this period, heightened uncertainty leads US banks that face liquidity shortage to hoard liquid assets rather than lend to foreigners. Such coordinated decisions by the US banks put upward pressure on FX swap rates.

The FX swap market also affects the cost of Eurodollar funding indirectly through the FX dealers. In essence, most deficit agents might acquire dollars by relying entirely on the private FX dealing system. Two different types of dealers in the FX market are typical FX dealers and speculative dealers. The FX dealer system expedites settlement by expanding credit. In the current international order, the FX dealer usually has to provide dollar funding. The dealer creates a dollar liability that the deficit agent buys at the spot exchange rate using local currency, to pay the surplus country. The result is the expansion of the dealer’s balance sheet and its exposure to FX risk. The FX risk, or exchange risk, is a risk that the dollar price of the dealer’s new FX asset might fall. The bid-ask spread that the FX dealer earns reflects this price risk and the resulting cost of hedging.

As a hedge against this price risk, the dealer enters an FX swap market to purchase an offsetting forward exchange contract from a speculative dealer. As Stigum shows, and Mehrling emphasizes, the FX dealer borrows term FX currencies and lends term dollars. As a result of entering into a forward contract, the FX dealer has a “matched book”—if the dollar price of its new FX spot asset falls, then so also will the dollar value of its new FX term liability. It does, however, still face liquidity risk since maintaining the hedge requires rolling over its spot dollar liability position until the maturity of its term dollar asset position. A “speculative” dealer provides the forward hedge to the FX dealer. This dealer faces exposure to exchange risk and might use a futures position, or an FX options position to hedge. The point to emphasize here is that the hedging cost of the speculative dealer affects the price that the normal FX dealer faces when entering a forward contract and ultimately determines the price of Eurodollar funding.

The critical question is, what connects the domestic US markets with the Euromarkets as mentioned earlier? In different maturity ranges, US and Eurodollar rates track each other extraordinarily closely over time. In other words, even though spreads widen and narrow, and sometimes rates cross, the main trends up and down are always the same in both markets. Stigum (2007) suggests that there is no doubt that this consistency in rates is the work of arbitrage.

Two sorts of arbitrages are used to link US and Eurodollar rates, technical and transitory. Opportunities for technical arbitrage vanished with the movement of CHIPS to same-day settlement and payment finality. Transitory arbitrages, in contrast, are money flows that occur in response to temporary discrepancies that arise between US and Eurodollar rates because rates in the two markets are being affected by differing supply and demand pressures. Much transitory arbitrage used to be carried on by banks that actively borrow and lend funds in both markets. The arbitrage that banks do between the domestic and Eurodollar markets is referred to as soft arbitrage. In making funding choices, domestic versus Eurodollars, US banks always compare relative costs on an all-in basis.

But that still leaves open the question of where the primary impetus for rate changes typically comes from. Put it differently, are changes in US rates pushing Eurodollar rates up and down, or vice versa? A British Eurobanker has a brief answer: “Rarely does the tail wag the dog. The US money market is the dog, the Eurodollar market, the tail.” The statement has been a truth for most parts before the great financial crisis. The fact of this statement has created a foreign contingent of Fed watchers. However, the direction of this effect might have reversed after the great financial crisis. In other words, some longer-term shifts have made the US money market respond to the developments in the Eurodollar funding.

This was one of the lessons from the US repo-market turmoil. On Monday, September 16, and Tuesday, September 17, Overnight Treasury general collateral (GC) repurchase-agreement (repo) rates surprisingly surged to almost 10%. Two factors made these developments extraordinary: First, the banks, who act as a dealer of near last resort in this market due to their direct access to the Fed’s balance sheets, did not inject liquidity. Second, this time around, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), which is replacing LIBOR to measure the cost of Eurodollar financing, also increased significantly, leading the Fed to intervene directly in the repo market.

Credit Suisse’ Zoltan Poszar points out that an increase in the supply of US Treasuries along with the inversion in the FX-hedged yield of Treasuries has created such anomalies in the US money market. Earlier last year, an increase in hedging costs caused the inversion of a curve that represents the FX-hedged yield of Treasuries at different maturities. Post- great financial crisis, the size of foreign demands for US assets, including the US Treasury bonds, increased significantly. For these investors, the cost of FX swaps is the primary factor that affects their demand for US assets since that hedge return, called FX-hedged yield, is an important component of total return on investment. This FX-hedged yield ultimately drives investment decisions as hedge introduces an extra cash flow that a domestic bond investment does not have. This additional hedge return affects liquidity considerations because hedging generates its own cash flows.

The yield-curve inversion disincentivizes foreign investors, mostly carry traders, trying to earn a margin from borrowing short term to buy Treasuries (i.e., lending longer-term). Demand for Eurodollars—which are required by deficit agents to settle payment obligations—is very high right now, which has caused the FX Swap rate-LIBOR spread to widen. The demand to directly raise dollars through FX swaps has driven the price increase, but this also affects investors who typically use FX swaps to hedge dollar investments. As the hedge return falls (it is negative for the Euro), it becomes less profitable for foreign investors to buy Treasury debt. More importantly, for foreign investors, the point at which this trade becomes unprofitable has been reached way before the yield curve inverted, as they had to pay for hedging costs (in yen or euro). This then forces Treasuries onto the balance sheets of primary dealers and have repercussions in the domestic money market as it creates balance sheet constraints for these large banks. This constraint led banks with ample reserves to be unwilling to lend money to each other for an interest rate of up to 10% when they would only receive 1.8% from the Fed.

This seems like some type of “crowding out,” in which demand for dollar funding via the FX swap has driven up the price of the derivative and crowded out those investors who would typically use the swap as a hedging tool. Because it is more costly to hedge dollar investments, there is a risk that demand for US Treasuries will decrease. This problem is driven by the “dual-purpose” of the FX swaps. By directly buying this derivative, the Fed can stabilize prices and encourage foreign investors to keep buying Treasuries by increasing hedge return. Beyond acting to stabilize the global financial market, the Fed has a direct domestic interest in intervening in the FX market because of the spillover into US money markets.

The yield curve that the Fed should start to influence is the FX-hedged yield of Treasuries, rather than the Treasury yield curve since it encompasses the costs of US dollar funding for foreigners. Because of the spillover of FX swap turbulences to the US money markets, the FX swap rate will influence the US domestic money market. If we’re right about funding stresses and the direction of effects, the Fed might have to start adding FX swaps to its asset purchasing program. This decision could bridge the imbalance in the FX swap market and offer foreign investors a better yield. The safe asset – US Treasuries – is significantly funded by foreign investors, and if the FX swap market pulls balance sheet and funding away from them, the safe asset will go on sale. Treasury yields can spike, and the Fed will have to shift from buying bills to buying what matters– FX derivatives. Such ideas might make some people- especially those who believe that keeping the dollar as the world’s reserve currency is a massive drag on the struggling US economy and label the dollar’s international status as an “an exorbitant burden,”- uncomfortable. However, as Stigum reminded us, the market for Eurodollar deposits follows the sun around the globe. Therefore, no one, including and especially the Fed, can hide from its rays.

Elham Saeidinezhad is lecturer in Economics at UCLA. Before joining the Economics Department at UCLA, she was a research economist in International Finance and Macroeconomics research group at Milken Institute, Santa Monica, where she investigated the post-crisis structural changes in the capital market as a result of macroprudential regulations. Before that, she was a postdoctoral fellow at INET, working closely with Prof. Perry Mehrling and studying his “Money View”. Elham obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Sheffield, UK, in empirical Macroeconomics in 2013. You may contact Elham via the Young Scholars Directory

Jack Krupinski is a student at UCLA, studying Mathematics and Economics. He is pursuing an actuarial associateship and is working to develop a statistical understanding of risk. Jack’s economic research interests involve using the “Money View” and empirical methods to analyze international finance and monetary policy.